A new Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) vaccine is entering human trials. If it proves successful, it could potentially protect against mononucleosis — and even multiple sclerosis (MS).

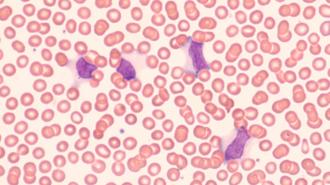

The virus: EBV is a member of the herpes family that spreads to people mainly through saliva. An estimated 9 out of 10 adults have been infected by the virus at least once, but many don’t know it, as infections are often asymptomatic.

Like other herpesviruses — which include the viruses behind chickenpox, shingles, and cold sores — once EBV infects a person, it remains in their body forever, hiding out inside their cells, but the virus can periodically reactivate, causing new symptoms.

An estimated 9 out of 10 adults have been infected by the Epstein-Barr virus at least once.

The impact: EBV is primarily known for causing mono — the “kissing disease” characterized by extreme fatigue, fever, and sore throat, which can last for weeks or even months. But it’s long been associated with increased risk of certain cancers and autoimmune diseases, too.

In January 2022, a Harvard-led research team published a study of 10 million young adults, which found that those who’d had an EBV infection were 32 times more likely to develop MS, a potentially debilitating disease of the nervous system.

“In practical terms, if you’re not infected with EBV, your risk of MS is virtually zero.”

Alberto Ascherio

“The hypothesis that EBV causes MS has been investigated by our group and others for several years, but this is the first study providing compelling evidence of causality,” said senior author Alberto Ascherio.

“This is a big step because it suggests that most MS cases could be prevented by stopping EBV infection,” he continued, “and that targeting EBV could lead to the discovery of a cure for MS.”

In a quote to the New York Times, Ascherio went further: “In practical terms, if you’re not infected with E.B.V., your risk of M.S. is virtually zero.”

An EBV vaccine: The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) has now launched a phase 1 trial of an EBV vaccine, which is only the second shot to reach this development stage in the past decade.

NIAID’s shot works by targeting a molecule found on the surface of the virus and the cells it infects, called glycoprotein 350. This is the same molecule that the immune system’s neutralizing antibodies attack when it’s fighting an EBV infection.

NIAID’s candidate is only the second EBV vaccine to reach human trials in the past decade.

The small trial will enroll 40 healthy people between the ages of 18 and 29. Half will have antibodies indicating they’d been infected by EBV before while the other half won’t. Each will receive three doses of the EBV vaccine: one when the study begins, one at day 30, and one at day 180.

The goal of this trial is to determine the safety of the vaccine and to see what kind of immune response it prompts.

The big picture: Researchers have been trying to vaccinate against EBV for decades without success.

One problem is that vaccines are designed to trigger an immune response, and herpesviruses are really good at hiding from our immune system. Another is that EBV has never been a huge research priority — almost everyone who gets infected gets over it without much fuss.

“People are rethinking the value of an EBV vaccine, as we’ve seen that it’s much better not to get infected at all.”

Hank Balfour

However, the knowledge that stopping the virus could also mean stopping MS has given new focus to the effort. Meanwhile, advances in vaccine tech — such as the mRNA platform Moderna is using for another EBV vaccine currently in trials — have researchers optimistic that an effective EBV vaccine is just on the horizon.

“For a long time, there’s been this known association between EBV and MS, but when I would apply for grants, people would still say that EBV has little if anything to do with MS,” Hank Balfour, a virologist at the University of Minnesota, told the Guardian in March.

“But now [that the Harvard paper has been published], people are rethinking the value of an EBV vaccine, as we’ve seen that it’s much better not to get infected at all,” he continued.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.