A new type of molecular test that quickly identifies targets could transform how we monitor human disease, crop health, and more.

The challenge: Molecular tests hunt for a specific molecule — PCR tests for COVID-19, for example, look for bits of the coronavirus’ genetic material in nasal swabs.

Molecular tests like this are highly accurate, but they’re also expensive and time-consuming, partly because they require “target amplification,” a process that creates copies of the target molecule in the sample (if it’s present) so that it’s easier to detect.

This process has to be repeated many times — PCR tests go through dozens of cycles.

“The trick is to sculpt light at the molecular scale.”

Jen Dionne

What’s new? A Stanford University-led team of researchers has now developed a new type of molecular test that’s fast and capable of detecting targets — like coronavirus — without the need for amplification.

The way it’s designed, the Stanford molecular test can also hunt for multiple targets in a single sample simultaneously, or precisely measure the amount of a target in a sample.

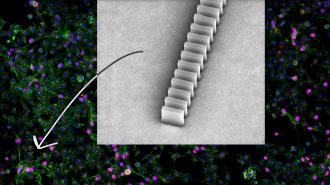

How it works: The test uses an array of incredibly tiny silicon boxes, just 500 nanometers high, on top of a silicon chip. When near-infrared light is shone on the chip from below, the light reflects off whatever is on top of each box in such a way that the molecule can be identified.

“The trick is to sculpt light at the molecular scale,” said co-developer Jen Dionne.

To demonstrate how this could be used to detect COVID-19, the researchers created single-strand DNA fragments designed to bind to a target coronavirus gene. After attaching those fragments to the tops of the silicon boxes, they placed the whole test in a buffer solution.

They then added the target coronavirus molecules to the solution at a concentration similar to what you’d find in a nasal swab sample. Within 5 minutes, the genes matched up with the DNA fragments on the boxes, enabling the detection of the virus — without any target amplification.

To use the molecular test to hunt for multiple targets at once, you’d top boxes with different bait. Targets could be DNA, RNA, proteins, or small molecules, and there’s really no limit to the number you could test for — 160,000 boxes can fit in one square centimeter of space.

“Our platform promises unique possibilities for widely scaled and frequently administered genetic screening.”

Hu, J. et al.

Looking ahead: The researchers have formed a startup, Pumpkinseed Bio, to commercialize their molecular test, which they say could be used to test the immunity of crops, quickly screen people for multiple diseases at once, and much more.

“Our platform promises unique possibilities for widely scaled and frequently administered genetic screening for the future of precision medicine, sustainable agriculture, and environmental monitoring,” they write in Nature Communications.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.