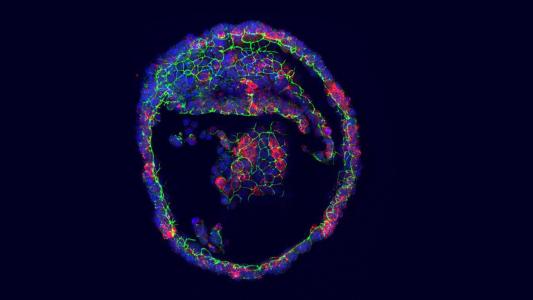

Building on seven years of previous research, scientists at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science have now grown a mouse embryo in a bottle — ex utero — to the stage of developing organs and limbs. It is the furthest a mouse embryo has grown outside of a uterus before, and it could open the door to new possibilities for studying how mammals develop — and what could go wrong during that process.

And not just mice.

“This sets the stage for other species,” Weizmann developmental biologist and team lead Jacob Hanna told MIT Technology Review. “I hope that it will allow scientists to grow human embryos until week five.”

Mouse in a Jar

The mouse embryos were grown in a jar for up to 11 to 12 days, a hair over half of a mouse’s gestation period.

To do so, the team developed a technique — to be published in Nature — that involves rotating bottles. The bottles contain blood serum from human umbilical cords, per Technology Review, as well as pumped-in oxygen.

This gets the crucial gas infused into the cells, which Hanna compared to a COVID-19 patient on a ventilator, where it powers blood and organ systems.

Getting the air pressure and oxygen levels right was the hardest part, Hanna told Science; “We learned how to control the ventilation system.”

Growing the mouse embryo ex utero was a two step process. First, the team had to extract the embryo from a pregnant mouse and grow it on a culture plate from day 5 to day 7 of gestation. That’s when the embryos go through gastrulation, going from a hollow tennis ball of cells to a structure where specialized cells are destined to form specific tissues.

Once they hit that point, the mouse embryos go into the rotating bottles, where they were grown all the way until the point of developing hind legs, the team reports in their Nature paper.

The mouse embryo dies beyond this point because it becomes too large for the pumped-in oxygen to effectively diffuse into it.

“It looks very spectacular,” Alexander Meissner, a developmental biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics uninvolved with the study, told Science. “The fact that (the researchers) can culture these embryos and keep them alive for such a long time — it’s amazing.”

Cracking Open the Biological Black Box

“Establishment of the mammalian body plan occurs shortly after the embryo implants into the maternal uterus, and our understanding of post-implantation developmental processes remains limited,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

In other words: we can’t see very well what happens, because it happens in the uterus. This key stage of development takes place in a biological black box, limiting what scientists can learn about mammalian development.

According to Popular Mechanics, the new system will allow researchers to study the impact of numerous variables on an embryo’s development. Everything from genetic modification to tissue manipulation and changing of the chemical environment may be possible.

The rolling bottle system “opens new doors by making embryos accessible for a detailed study of many aspects of their development,” CalTech developmental biologist Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz told Science, and “will make a big contribution to the field, which we are certainly planning to exploit.”

That system is still complex and expensive, and can be improved upon; being able to grow the mouse embryo entirely in the bottle, for example, would hugely simplify the process.

Being able to see deeper into an embryo’s development may not only help researchers understand just exactly what goes on in the process, but also when and where it may go wrong.

When the mouse embryo research is considered together with new work studying blastoids (clumps of engineered cells that can act as imitation embryos) the “two milestones could combine to unlock the mysteries of very early pregnancy, with the fewest possible ethical quagmires,” Popular Mechanics’ Caroline Delbert writes.

Beyond the Mouse Embryo

These ethical quagmires are not trivial. Hanna is clear about the research opening up the possibility of studying human embryos up until week five of their gestation.

Already the ethical implications have set in. Going that far into the first trimester may make research abut abortion, and all the ethical, moral, and social implications that make it a third rail.

While growing a mouse embryo for eleven days in a rotating jar doesn’t mean an ex utero human embryo is immediately behind, it does serve as something of a proof of concept.

“I do understand the difficulties. I understand. You are entering the domain of abortions,” Hanna told MIT Technology Review.

He points out, however, that researchers already study human embryos up to five days old in IVF clinics, which are often destroyed in the process.

“We need to see human embryos gastrulate and form organs and start perturbing it. The benefit of growing human embryos to week three, week four, week five is invaluable,” Hanna said. “I think those experiments should at least be considered. If we can get to an advanced human embryo, we can learn so much.”

Being able to see into the development process could reveal why so many embryos fail to implant in the uterus, Delbert notes — something crucial to IVF patients

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.