Ha! You thought you weren’t going to learn anything new, didn’t you? Hey Dope Science, I already know about ketamine and mushrooms. I’m a drug expert! Well, we’ve got something a bit farther afield this time — ever heard of ibogaine?

The hallucinogenic drug may be best known for being Hunter Thompson’s satirical explanation for the behavior of 1972 presidential candidate Ed Muskie. “If you eat it — just a chunk of it — you can sit for three days in a very quiet stupor, without sleeping, and watching a water hole,” he wrote.

Ibogaine’s been at the center of what Kenneth R. Alper, associate professor of psychiatry and neurology at New York University School of Medicine, dubs a “medical subculture.” Time for the Drug Guide to dive in.

What’s this ibogaine drug now?

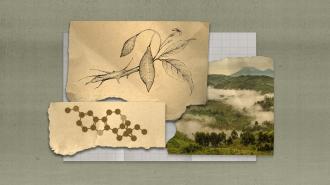

Ibogaine comes from the iboga plant, Tabernanthe iboga Baill. It’s a bushy shrub, found in Congo, the Republic of Congo, and Gabon, which has been cultivated across West Africa. The psychoactive properties of the plant play a role in religious rites and ceremonies across the region.

For those who practice Bwiti, a religion in Gabon, the iboga plant is a central part of their religious rites and ceremonies. Through dance, music, and the consumption of moderate doses of the psychedelic plant, they foster community during weekly ceremonies. Higher doses are used for initiation rites or those dealing with major life events or trauma. These high doses can cause long, intense dissociative experiences. The iboga plant is seen as a direct connection to ancestors and spirituality.

Why do people get high on this stuff?

According to the Global Ibogaine Therapy Alliance, a not-for-profit corporation which supports the use of ibogaine for religious and medical purposes, low doses of ibogaine act as a stimulant. When taken in larger doses, it causes dream-like states, dissociation, and at high enough doses, hallucinations.

What’s the new medical research?

Perhaps not new, per se. Medical interest in ibogaine stems from its possible use in treating substance abuse, especially opioid addiction. The pharmacology of ibogaine is complex, and research is hamstrung by a lack of funding and the drug’s Schedule I classification in the U.S.

Preliminary research has shown ibogaine to be effective at detoxification of opioid users, and seems to suppress a further desire to use as well. As of NYU’s Kenneth R. Alper’s 2017 paper, the cause of this effect is currently “unknown and likely novel.”

The Promise and the Pitfalls

Howard Lotsof sparked the use of ibogaine as an addiction treatment. In the summer of 1962, Lotsof, then a 19-year-old heroin addict in Brooklyn, took ibogaine. As the Global Ibogaine Therapy Alliance — which Lotsof founded — tells it, he was surprised to find that, although he did not use heroin for hours, he had no withdrawal symptoms. Lotsof began administering the drug to fellow addicts, and found they had similar results. Not only did they not suffer from withdrawal symptoms, but many had gained insights into their addiction during their trips.

Even as a graduate of NYU film school, Lotsof eventually convinced the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to study ibogaine. From 1991 to 1996, the government agency funded basic research into the way ibogaine moves throughout the body and its toxicity. Eventually, a study of the effects of ibogaine on cocaine dependency got FDA approval in 1993. The study dissolved into intellectual property disputes, its results lost. Since NIDA ended their ibogaine project, there has been no clinical research into ibogaine in the U.S., NYU’s Alper wrote in Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs.

The iboga plant’s somnambulistic sorties into the mind are apparently not for the faint of heart. They may be accompanied by anxiety and apprehension, a host of physical side effects, and even fatalities from cardiac arrest.