Amid the turmoil of the Great Depression, one of history’s great intellectuals shared a very unintellectual hot take: He blamed automation for taking all the jobs and causing the economic chaos that would define the 1930s.

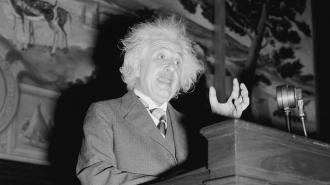

His name? Albert Einstein.

In a 1933 speech, the famous physicist argued that automation, rather than war debts, was the primary cause of the economic turmoil in Germany — his home country — and the United States. The speech, titled “America and the World Situation,” was covered by the New York Times under the headline “Einstein Traces Slump to Machine.”

On the same page was a full transcript of the address in which Einstein stated his thesis:

According to my conviction, it cannot be doubted that the severe economic depression is to be traced back for the most part to internal economic causes: the improvement in the apparatus of production through technical invention and organization has decreased the need for human labor, and thereby caused the elimination of a part of labor from the economic circuit and thereby caused a progressive decrease in the purchasing power of the consumer.

His evidence? The United States was also in a depression, without the crushing war debts Germany had. However, both countries were seeing rapid automation in their economies — the common denominator in his mind. It was a diagnosis he’d hinted at years prior in a 1931 Berlin speech that blamed the “great distress of current times as the result of man-made machines.”

Einstein wasn’t alone. Only a year prior, economist John Maynard Keynes had popularized the term “technological unemployment,” bringing the notion attention shortly after the start of the Great Depression. While Keynes would consider automation a factor in the downturn, he was optimistic in the long-run for it to improve quality of life and reduce working hours. Einstein didn’t seem to make any such optimistic caveats.

Einstein stressed that identifying automation, rather than post-war debts, as the key cause of economic strife would ease tensions between nations and reduce “a dangerous source of mutual embitterment of nations.” This was no doubt an allusion to the Treaty of Versailles, which Adolf Hitler blamed for Germany’s economic turmoil. A week after Einstein’s speech, Hitler would be appointed the chancellor of Germany.

Einstein and Keynes had succumbed to what we now called the “lump of labor fallacy” — the assumption that there is a finite amount of work for people to do. Permanent mass-unemployment did not persist, and Keynes’s prophecy of a four-day workweek never came to fruition.

Fear fearing automation

Ironically, the fear of automation stoked by high-profile figures like Einstein might well have unnecessarily dampened consumer sentiment by making unemployment feel inevitable and irreversible. It isn’t unreasonable to suggest this could well have made the Great Depression worse.

In his 2019 book “Narrative Economics,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert J. Shiller suggests that a “narrative epidemic” around automation taking all the jobs likely exacerbated the depression of 1873 and that a similarly “epidemic narrative” emerged in the years leading up to the Great Depression.

A few months after Einstein’s speech, FDR would be elected president of the United States. In his inaugural address, he uttered the famous words “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” — a notion worth remembering as a new “narrative epidemic” is set to take hold around AI and job automation.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.