On May 29, 2025, Freethink Media brought together visionary technologists, founders, and futurists in San Francisco to explore how breakthrough technologies — from AI to clean energy to synthetic biology — can help reinvent America for the 21st century. Curated by Peter Leyden in partnership with Freethink, “The Great Progression Begins Now” featured bold ideas, dynamic conversations, and a celebration of the innovators shaping what comes next. It was a night to frame the future — and to meet the people building it.

Ryan Phelan, co-founder of Revive & Restore, was one of three remarkable guests to take the stage that night.

During her conversation with Leyden, she explained how the same genomic tools that revolutionized healthcare are now being applied to conservation — rescuing endangered species and potentially reviving extinct ones. “Why shouldn’t we use the same genomic innovations that revolutionized healthcare to restore the natural world?” Phelan asked, framing bioengineering as a hopeful force for conservation rather than just disruption.

In a world of endless noise, Freethink Media creates live experiences that connect, inspire, and transform. Sign up to get notified of upcoming events.

The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and readability:

Peter Leyden: She is the partner in many ways with Stuart Brand, who is, for those young people here, an icon of the Bay Area and really one of the community builders. You and Stuart put together this — and you are now the driver of it — Revive & Restore. This is the space that I think most people do not really have their heads wrapped around much and how the incredible potential in this field.

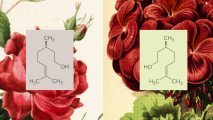

Ryan Phelan: Stuart and I started Revive & Restore back in 2012. I had been a serial entrepreneur in healthcare, primarily in personalized medicine. I had seen, in the early 2000s, the advent of the Human Genome Project, and I knew how powerful it would be for human health, for personalized, targeted medication, for interventions at a personal level.

I rode that wave of innovation for literally two decades in healthcare. I realized that I wanted to really think about how to apply genomic technologies to the other species on the planet, and my husband, who is obviously very visionary, was sort of saying, “Well, how far can this technology go?”

We took a trip to George Church’s lab at Harvard, and I had been on George’s Personal Genome Project board, and he is the man when it comes to genome engineering. He started showing us what was then the state of the art in 2012 for genome editing. Nothing like CRISPR today, but George was totally ahead of the curve, and he was saying we could make this transformative technology happen.

Stuart said immediately, “Well, I want to bring back a passenger pigeon that has been gone just 100 years,” and George said, “I want to bring back a woolly mammoth.” One thing led to another, and Ryan here said, “Well, what can we do for all the endangered species so they don’t go extinct?” And that was the really nice convergence.

So, long story short, I run Revive & Restore with a great team of seven people and about 400 conservationists, genome engineers, field biologists, all working in what we call the field of “genetic rescue,” helping species move away from the brink. We’re using all the tools of technology, from genome sequencing to advanced reproductive technologies, like cloning, to genome editing.

Leyden: A lot of what’s driving your Revive & Restore is the absolutely atrocious —

Phelan: The sixth mass extinction that’s going on.

Leyden: So give a little bit of a sense of like how bad it is and how we’ve got to shift from the old ways of dealing with this into probably radically new ones, including bioengineering.

Phelan: So, for those of you who don’t think about conservation, wildlife conservation, not energy conservation, think the word “conservative” — that’s really been the way that the field of conservation has moved forward. Very guardedly. Think about protecting the redwoods, saving the redwoods as a typical, quote, “conservation funder.” It’s a gross exaggeration, but it’s been mostly about putting up barriers, protecting environments, and whether it’s marine or national parks, helping species live within a healthy ecosystem.

That’s awesome, and we need it more than ever. We need to figure out ways today to spare more land for the other species on the planet, but that doesn’t mean that conservation was ever very interventionist. I think the urgency today of all the challenges of living in a global environment that we all inhabit — where we have wildlife diseases, invasive species, and all the encroachment of the human habitat, the needs of agriculture, and ways that we have misused the land — all of that is absolutely exacerbated by climate change.

Species across the globe are being confined to very fragmented populations. You talked a lot about abundance here. Really, a healthy environment needs a bio-abundance of species to prosper, and they need to have connected corridors to move, to adapt, if they can, to a changing environment. I’m happy to talk about coral as an example.

Leyden: Didn’t you say something like 80% of the coral reefs are dying?

Phelan: Well, the projection is by 2050, 90% of the coral reefs will be gone. Now, that’s if we don’t intervene. They’ve been saying that statistic for quite a while, and it’s not getting better.

In 2023, there was a study that 85% of the world’s coral bleached. Now, bleaching, going white, is not death — yet. Coral can rebound from warming waters if they don’t have repeated insults, but they are having repeated insults. They can only have so many years where they bleach, and then they’re done.

One of the biggest challenges in this field has been whether or not traditional conservation biologists, field biologists, would be willing to intervene. When we started and looked at this field in 2015, I spoke with marine biologists all over the world, and they said, “There is so little coral being left on the reefs, we don’t dare intervene.” They didn’t want to take coral out to genome sequencing, much less think about what they could do about the situation.

“Doing nothing is taking action, and that inaction is going to deplete the coral.”

Ryan Phelan

I started talking about genome engineering: What if we could find coral that were more resistant to warming waters and transplant them to another place, like selective breeding is done? Or could we genome engineer? Could we find particular regions of the genome that are making them more thermal tolerant?

Fast track forward. Now, we’ve been working with coral on some 13 different projects around the world. We fund the research to do this cutting-edge research. More and more coral biologists are saying, “We have to do something.” There is no standing by, and doing nothing is taking action, and that inaction is going to deplete the coral.

Of course, the coral are so fundamental to livelihoods all over the world. A billion people count on coral reefs for their livelihood. They protect our infrastructure all over the world. They dissipate wave action and hurricanes.

When I think about this whole environment of how challenging it is for a species on the planet, we have to figure out how we can apply new technologies.

Our field at Revive & Restore is using genomic technologies, but we have to couple that with new state-of-the-art technologies. Everything from remote sensing, Planet Labs-equivalent, to sensors, both marine and terrestrial, to eDNA, environmental DNA that we can identify, “Are things getting better or worse?” We need to couple it with AI that can really fast track a lot of this innovation, because we’re not going to get there without it.

Leyden: What do you mean intervening? Bioengineering, genetic understanding, cloning, a lot of stuff pushes it, so we’re doing that. But let’s shift to a couple other fields that are in the bioengineering space. Cellular agriculture. People talk about cultured meat, and there’s been a kind of blowback and pushback. Talk about the state of where that is and how important that could be, again, from a climate angle.

Phelan: From a climate and human habitat and everything else perspective, going back to why conservation has been focused on land protection and marine protection is because of the overuse: the over-harvesting and the encroachment of human habitation. Number one problem that we have right now is land use for agricultural purposes. If we can find a way to take the pressure off of land use — they call it “land sparing” — to help with environmental problems, it would be a boon to civilization in the future.

Now, that doesn’t mean that all cattle are bad and that it can’t coexist, but we have to find a way to reduce that, whether it’s for carbon emissions or just the healthiness of our planet to be relying so much on that system.

“The biggest challenges in all of the field that I work in … is market adoption and regulatory path.”

Ryan Phelan

Cellular agriculture for meat consumption could be a very, very big deal if we can get a big enough market, if they can improve the products so that as consumers we all feel really good about it, and if the regulatory path in the US, in particular, as well as in Europe, actually finds a way to allow cell-based meats to go forward.

The same is true for aquatic species. Right now, a huge percentage of the fish that we eat, I think it’s something like over 60%, is all done by aquaculture. This is not a new terrain for us to be figuring out how to bring farmed fish to market, but to actually be able to do it using synthetic biology — to create cell-based fish and other marine species — is huge. Again, it would be incredibly friendly to the environment.

The biggest challenges in all of the field that I work in, whether it was in human medicine or now in conservation, is market adoption and regulatory path. Obviously, funding is critical to all of this to move forward, but that has been really challenging.

Leyden: I mean, there’s enough resistance to AI, but to bioengineering, you’ve got, like you say, people that [say], “Don’t touch nature.” There’s probably even a lot of people in this room that are going to have a hard time with that. You’ve got religious pieces of it, like, “Don’t touch God’s work.” How transformative and how important do you think bioengineering is to actually solving climate change and really a sustainable planet? How much do we really have to start focusing on how to get beyond the pushback, would you say?

Phelan: So, you know, obviously clean energy is key. So, you know, I’m not going to touch that.

Leyden: Yeah, yeah, there is a whole crew out there.

Phelan: And the whole geoengineering, I’m not going to touch either, because that’s a whole other field. But on the biotech side, I think it is a game changer if you want to create a healthy planet with biodiversity and bioabundance. We know that you cannot create planetary health without it.

When I realize, and I think about the amount of funding and emphasis, including in the VC culture that goes into climate tech for ensuring that there’s a healthy planet, it was like, “Well, what’s going to be on the planet?” You know, I mean, we don’t want to live in a depopulate world, right? All of these technologies have to converge and work together.

Leyden: This is a little bit moving towards our next phase. Are you optimistic about that? How hard is the road for bio?

Phelan: We’re not at that inflection point with the Moore’s law in biotechnology. But I think with AI, we could be. I think AI is the big game changer here. CRISPR and the follow-on technologies with genetic editing are going to be key. I think the reproductive technologies are going to be important, just like they have been for human medicine.

I think when we look at what are some of the game changers in healthcare in the past, it was in vitro babies. I mean, you know, there was a time we didn’t know what to do with it. It was ethically fraught. You know, the first test-tube babies were what they were called.

I think we’re going to see that same transformation where it’s like we take it for granted. Probably some of you in this room are the result of in vitro fertilization, or you certainly know people who have had children because of that technology. I think that’s going to happen, and we’re going to take it for granted. That was not regulated, by the way. In vitro fertilization is not regulated. I think we’re going to have to find ways to solve this regulatory burden that exists around genomic medicine.

Leyden: Well, it will be part of the reinvention of the Great Progression going forward. So anyhow, let’s have a good hand for Ryan Phelan.

In a world of endless noise, Freethink Media creates live experiences that connect, inspire, and transform. Sign up to get notified of upcoming events.