Rooftop coatings can keep homes cool — like cooling paper that helps radiate heat away. Or they can trap heat inside, keeping homes warm.

But what is the optimal rooftop coating for homes with both a hot and cold season?

Scientists have come up with an answer: an all-season smart-roof covering that keeps homes warm in the winter and cool in the summer.

The phase-shifting material uses a simple physics trick to get the job done, without added electricity.

Why it is different: Most temperature regulating roof coatings, like paint, membranes, or special shingles, are lightly colored to reflect sunlight. They can also absorb heat from the building and release it as thermal-infrared radiation, in a process called radiative cooling.

“This is energy-free, emission-free air conditioning and heating, all in one device.”

Junqiao Wo

But when winter comes, this can be a problem, as it radiates precious heat away from the house.

Now, a team at U.C. Berkeley invented a new type of coating, which can serve a dual purpose — heating and cooling — by automatically turning off radiative cooling in the winter. The material is called a temperature-adaptive radiative coating (TARC).

“Our all-season roof coating automatically switches from keeping you cool to warm, depending on outdoor air temperature. This is energy-free, emission-free air conditioning and heating, all in one device,” Junqiao Wu, a materials scientist at Berkeley, said in a statement.

The secret ingredient: The critical ingredient is vanadium dioxide, a material that has been used on window coatings and to conduct electricity in batteries. It acts like a metal to electricity but an insulator to heat — it can conduct electricity without conducting heat.

In other words, it has a remarkable ability to change phases. It shifts between being transparent and not absorbing thermal-infrared light and being a metal that absorbs thermal-infrared light. Swapping between phases is what makes this material so versatile on rooftops.

When vanadium oxide is at room temperature, the sun’s Earth-warming infrared radiation may travel through it. However, when the material reaches 153 F (67 C), its characteristics change — it changes phase. It begins to block infrared light, allowing the sun in when it’s chilly and casts a shadow, or blocks the sun when it’s hot, reports Popular Science.

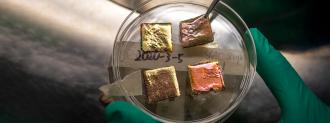

How well it works: To test the material in a rooftop system, the team created a 2-centimeter-by-2-centimeter TARC thin-film patch. Wu volunteered his own home as the first test site. The team installed many patches, which looked like Scotch tape, on Wu’s home last summer.

They then utilized the data from the experiment to predict how TARC might work year-round in 15 distinct climatic zones across the continental United States.

“You cannot just [test] it in the lab,” Wu told Popular Science, “because in the lab, you don’t get sunlight, you don’t get wind, you don’t face the sky.”

The team found that TARC beat present roof coverings in 12 of the 15 climatic zones and reported their findings in the journal Science. The material worked particularly well in locations with large temperature differences, like New York City’s summer and winter or San Francisco Bay Area’s night and day. In addition to the simulations, they used infrared spectroscopy experiments, which validated their findings.

“Simple physics predicted TARC would work, but we were surprised it would work so well,” said Wu. “We originally thought the switch from warming to cooling wouldn’t be so dramatic. Our simulations, outdoor experiments, and lab experiments proved otherwise – it’s really exciting.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].