If progress has stalled, we need to know why

Only then will we know what, if anything, we can do to re-accelerate it.

The following is Chapter 6, Section 2, from the book The Techno-Humanist Manifesto by Jason Crawford, Founder of the Roots of Progress Institute. The entirety of the book will be published on Freethink, one week at a time. For more from Jason, subscribe to his Substack below.

In part 1, we saw that the long-term pattern of growth is one of acceleration.

But the standard disclaimer for financial investments also applies to human progress: past performance does not guarantee future results.

Indeed, some claim that growth in the West has already slowed, at least compared to its peak around the first half of the 20th century. Tyler Cowen wrote a book with this thesis, The Great Stagnation:1

Today … apart from the seemingly magical internet, life in broad material terms isn’t so different from what it was in 1953. We still drive cars, use refrigerators, and turn on the light switch, even if dimmers are more common these days. … Life is better and we have more stuff, but the pace of change has slowed down compared to what people saw two or three generations ago.1

Cowen had been influenced by conversations with Peter Thiel, who leads the VC firm Founder’s Fund.2 Around the same time, Founders Fund published a manifesto, “What Happened to the Future?”, with a subtitle that became a Silicon Valley catchphrase: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”3 A few years later, in an interview with Cowen, Thiel said:

I think we’ve had a lot of innovation in computers, information technology, Internet, mobile Internet in the world of bits. Not so much in the world of atoms, supersonic travel, space travel, new forms of energy, new forms of medicine, new medical devices, etc.4

In The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Robert Gordon surveyed American economic progress over almost 150 years, and concluded that living standards had improved faster from 1870 to 1970 than they have in the decades since:

[E]conomic growth since 1970 has been simultaneously dazzling and disappointing. … advances since 1970 have tended to be channeled into a narrow sphere of human activity having to do with entertainment, communications, and the collection and processing of information. For the rest of what humans care about—food, clothing, shelter, transportation, health, and working conditions both inside and outside the home—progress slowed down after 1970, both qualitatively and quantitatively.5

Knowing how much progress has been made in recent decades, I was initially skeptical about claims of stagnation. “We wanted flying cars, instead we got a supercomputer in everyone’s pocket and a global communications network to connect everyone on the planet to each other and to the whole of the world’s knowledge and culture”—when you put it that way, it doesn’t sound so bad.6 But I was eventually convinced by a systematic survey of the evidence. Progress has not ground to a halt, nor is it even slow compared to the pre-industrial era, but in the US at least, it has slowed relative to its peak in the late 19th to mid-20th century.

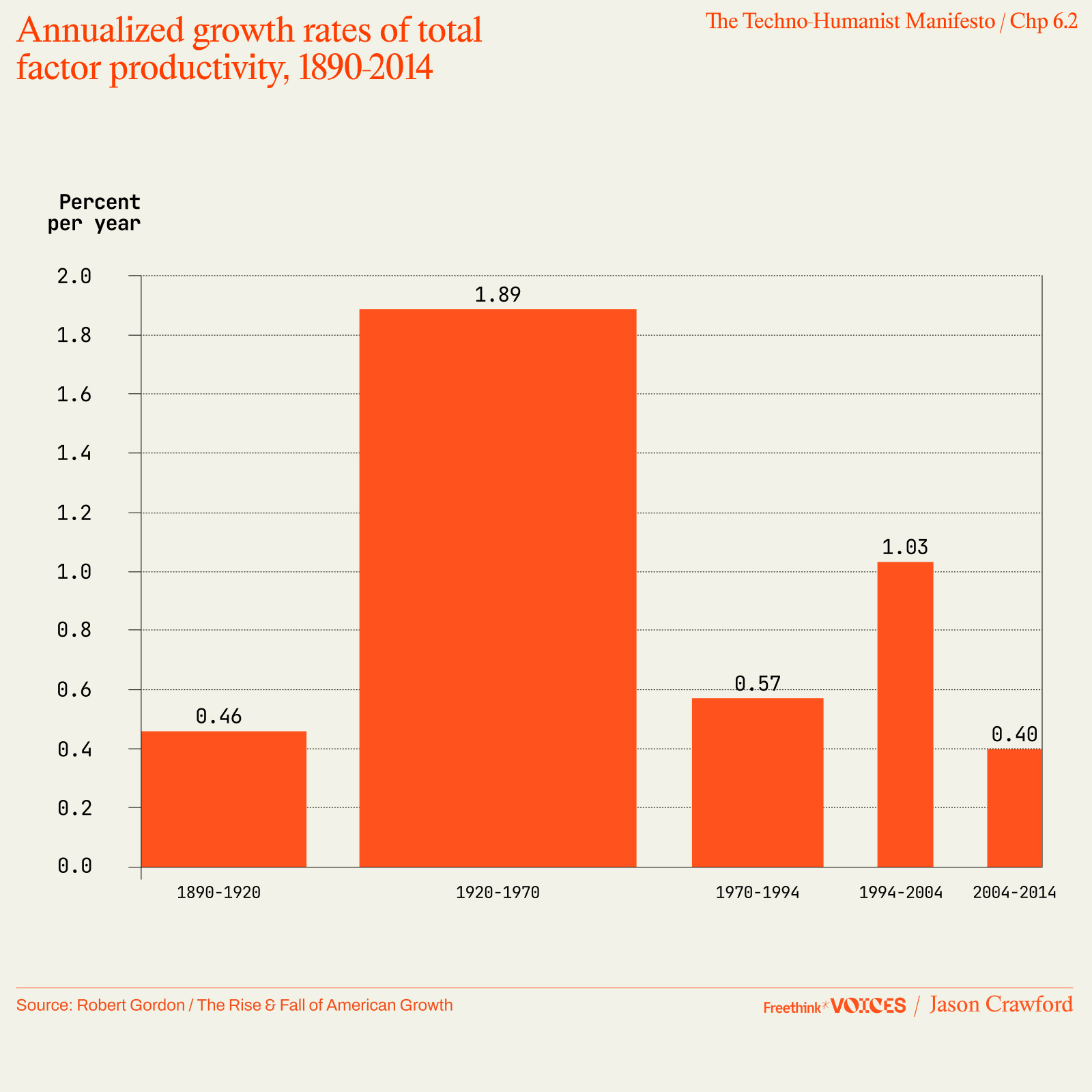

The slowdown can be seen from economic statistics. Gordon points out that growth in output per hour has fallen from an average annual rate of 2.82% in the period 1920–1970, to 1.62% in 1970–2014.7 He also analyzes TFP (total factor productivity, a residual calculated by subtracting out increases in capital and labor from GDP growth; what remains is assumed to represent productivity growth from technology). Annual TFP growth averaged 1.89% from 1920–1970, but closer to 0.5% since then, with the exception of a partially accelerated decade 1994–2004:8

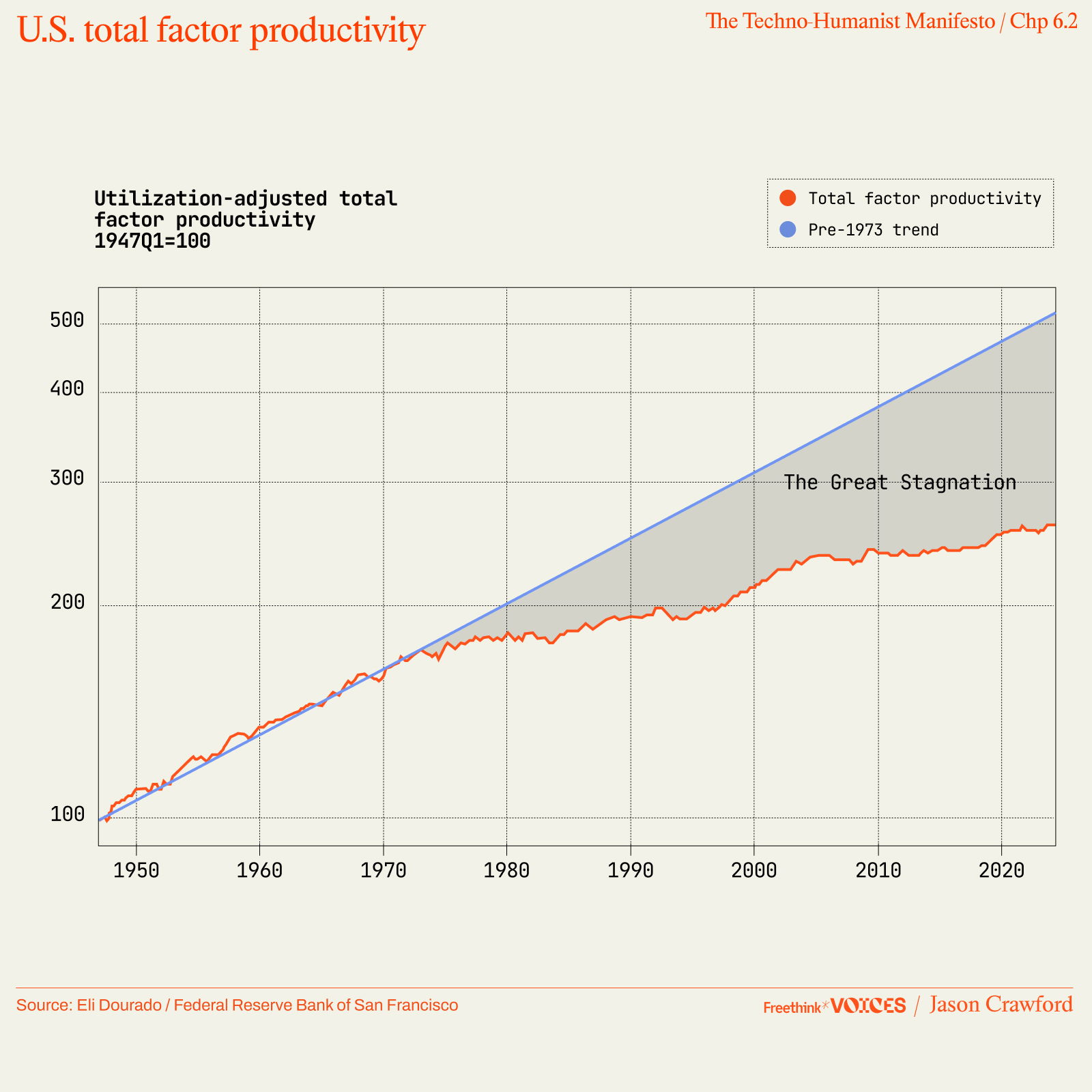

Here’s another view of TFP, extended to the 2020s (note the log scale; straight lines indicate constant growth rates):9

Measuring growth is hard. GDP is not a measure of economic production, and it does not capture consumer surplus: since you don’t pay for articles on Wikipedia, searches on Google, or entertainment on YouTube, a shift to these services away from paid ones actually shrinks GDP, but it represents consumer benefit and progress. Estimates of the consumer surplus of the internet, however, “are at least an order of magnitude smaller than the trillions of dollars of measured output lost to the productivity slowdown.”10 Further, Gordon points out that GDP has never captured consumer surplus, and there has been plenty of surplus in the past, such as free radio and television broadcasting, or the value of a patient’s life versus the cost of the penicillin that saved them. Nor is it only services or information technology that can deliver large consumer surplus: the refrigerator made food safer and gave us greater variety in our diets; the automobile cleared city streets of horse manure and urine.11 Altogether, it seems unlikely that unmeasured value creation can explain the GDP growth slowdown.

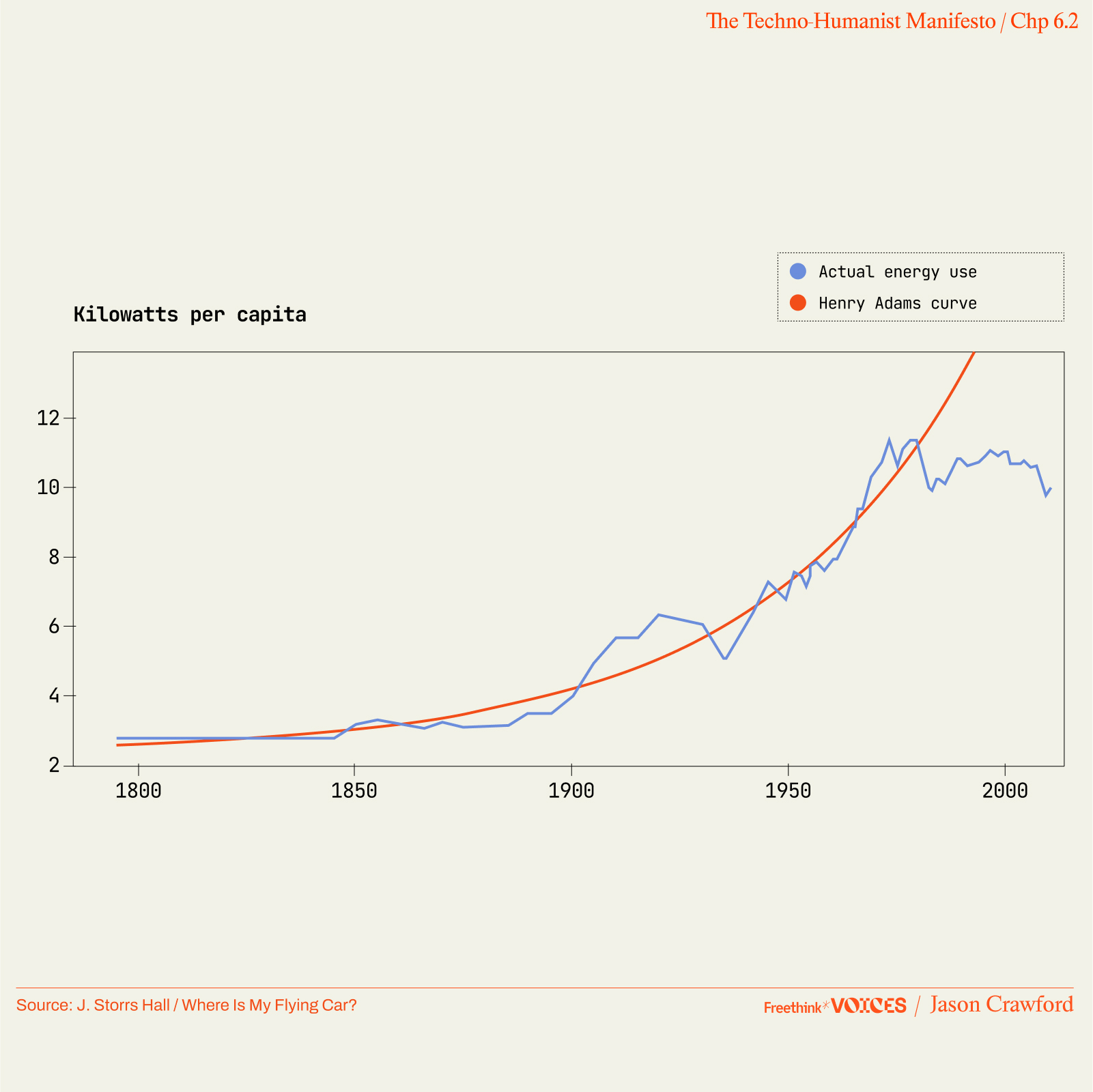

Other, less ambiguous metrics have also stagnated. The most striking is US energy usage per capita, which grew steadily for well over a century before flatlining around 1970.12 Some of this is the result of increased energy efficiency, but there was also improved energy efficiency in the past, and it’s implausible that greater efficiency can fully account for the ever-widening gap between the previous growth curve and actual usage, or that flat or declining resource usage is optimal for progress.

We can also see the slowdown qualitatively. Compare the last 50 years, 1975–2025, to the equivalent period a century earlier, 1875–1925. The last half-century has seen a revolution in information technology: the PC, the Internet, the smartphone. But in the earlier period, we also had a revolution in information technology: the telephone and the radio. And on top of that, we had the entire electrical power industry, including generators, light bulbs, and motors; the internal combustion engine, and the vehicles it made possible: the automobile and the airplane; the first synthetic plastics and fertilizers; and the establishment of the germ theory and its applications to public health, including improved water sanitation and some of the first vaccines.

The last 50 years have seen no comparable advances in manufacturing, energy, or transportation. There have been no new materials to replace steel, concrete, or plastic; no new power source to replace the internal combustion engine or the electric motor; no new vehicles to replace the automobile or the airplane. Our planes actually fly a bit slower than they used to.13 We haven’t ended any major diseases, the way we eliminated smallpox, malaria, or polio. One might argue about whether computers and the Internet are more or less of a revolution than telephone and radio, but it’s hard to maintain that a revolution in one field, or even two, is greater than five revolutions stacked together.

Consider also the technologies that were expected, but never arrived or haven’t come to fruition; or those that were launched, but aborted or stunted. Nuclear power was supposed to deliver cheap, abundant, reliable, clean energy, and it was on a strong growth trajectory until the 1970s—after which it stalled and plateaued at about 20% of US electricity generation.14 The Concorde offered supersonic passenger travel, but it was never affordable to the middle class, and service was canceled in 2003.15 The Apollo program promised a new Space Age, but after planting our flag on the Moon, no human has set foot there since 1972.16 A “War on Cancer” was declared in 1971; more than 50 years later, despite significant progress in mortality rates, we are still searching for a cure.17

Is all this just a blip in the long-run trend of acceleration, one that future economic historians will barely notice on their zoomed-out charts? Or is it the beginning of a historic reversal? Tyler Cowen saw the “great stagnation” as temporary: around the time of his book, he predicted that it would end within twenty years.18 Peter Thiel tends to blame “something in the culture that’s changed that makes us less ambitious, more risk-averse, more scared to try to do things,” and in particular a culture “that dislikes science and technology in just about all its forms.”19 In this view, stagnation can be reversed, but only by our will. Robert Gordon, in contrast, calls himself “the prophet of pessimism.”20 He sees no opportunities to improve life in the future as much as it was improved before 1970, and he notes that the social trends that contributed to growth, such as increasing education rates and women entering the workforce, have reached natural limits and plateaued.21 In a 2013 TED talk, he proclaimed “The Death of Innovation, the End of Growth.”22

In any case, if progress has stalled, that makes it all the more urgent to understand what drives it, what might cause it to slow down or stop, and what if anything we can do to re-accelerate it. In the next chapter, we’ll consider some of the most common reasons for skepticism about continued growth.

To be continued in Chapter 7.

1. Cowen, The Great Stagnation, Kindle location 92.

2. Cowen thanks Thiel in the acknowledgments, and dedicates the book to him and Michael Mandel, “who have blazed the way.”

3. Gibney, “What happened to the future?”; Gobry, “Facebook Investor wants Flying Cars, Not 140 Characters.”

4. Cowen, “Peter Thiel on Stagnation, Innovation, and What Not To Name Your Company.”

5. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, 2.

6. Crawford, “Technological Stagnation.”

7. Gordon, Rise and Fall, Table 18-4, 637.

8. Gordon, Rise and Fall, 575.

9. Dourado, “U.S. Total Factor Productivity.”

10. Syverson, “Challenges to Mismeasurement Explanations.”

11. Gordon, Rise and Fall, 242–4, 320–2.

12. J. Storrs Hall, Where Is My Flying Car?, 81. Because the growth in this metric was mentioned in the autobiography of Henry Adams (grandson of John Quincy Adams), Hall calls the long-term trend of about 7% annual growth in total energy usage the “Henry Adams Curve.”

13. Ledsom, “Why Is Your Flight Today Slower Today Than Ever Before?”

14. Lang, “Nuclear Power Learning and Deployment Rates.”

15. Gray, “Concorde: Nothing More Than a Footnote.”

16. Neufeld, “Why Has It Been 50 Years Since Humans Went to the Moon?”

17. Nixon signed the National Cancer Act in 1971; the media dubbed it a “war on cancer.” “National Cancer Act 50th Anniversary.”

18. Cowen, “Is the Great Stagnation Over?”

19. Kristol, “Transcript of Peter Thiel”; Theroux, “Developing the Developed World.”

20. Wellisz, “Prophet of Pessimism.”

21. Gordon, Rise and Fall, 641–2.

22. Gordon, “The Death of Innovation, The End of Growth.”