For the first time, a mini brain grown in a lab has produced detectable brain waves. Researchers hope that it can offer new ways to study brain disorders. But the brain-like “organoid” also raises difficult questions about when consciousness begins and where this research is going.

Brain waves are electrical impulses that traverse across neurons in the brain, conveying emotions, actions, and thoughts.

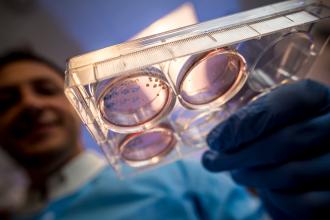

Alysson Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego, grew over 100 mini brains in Petri dishes in his lab. The results of his study were published Aug. 29 in the journal Cell Stem Cell. Now he plans to study neurological disorders, like autism or epilepsy, using the mini-organs as a model.

Brain organoids aren’t new — scientists have been creating them for a decade — but, unlike previous brain surrogates, Mutori’s have a functional, human-like neural network: a web of neurons that can transmit information across the brain. Mutori describes this as the “essence of brain activity.”

For this reason, until now, brain organoids only came in handy when studying diseases that leave visible marks on the brain. For example, Honjun Song, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania who does not work with Mutori, demonstrated the usefulness of brain organoids to study the Zika virus. That virus causes microcephaly, a condition that stunts fetal brain development and causes children to be born with unusually small heads. Song mixed Zika with brain organoids and observed brain cell death resembling that in a microcephalic brain.

But the possibilities of a lab-grown brain with a functional neural network are enticing. Many people suffer from neurological conditions, such as autism and epilepsy, which may leave the brain visibly intact. Psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression rarely show physical malformations. Instead, these conditions affect how the networks function — how neurons connect and send electrical impulses through the brain.

It takes a functioning brain to study neuron activity like that, but animal models fall short because human behaviors and brains are so different.

Muotri says that when we observe mouse behaviors and try to apply that to human behavior, we nearly always fall short. “The only way to really attack human conditions or diseases is to study the human brain,” he says.

But studying a brain while someone is using it is either highly invasive or extremely limited. Data acquisition is slow, and there’s only so much an fMRI of cerebral blood flow can tell us about what the brain is doing.

Growing mini brains on-demand — ones with actual brain waves — could enable researchers to rapidly carry out trials and test drugs that might lead to better treatments. Brain waves are electrical impulses that traverse across neurons in the brain, conveying emotions, actions, and thoughts.

Growing mini brains on-demand — ones with actual brain waves — could enable researchers to rapidly carry out trials and test drugs that might lead to better treatments.

It took Muotri 10 months to raise his army of pea-sized organoids. He put human stem cells in a Petri dish, sprinkled in features of a brain-like environment, and stepped back to watch them grow.

After just two months, electrodes in the Petri dish detected brain waves. The scant signals were weak and infrequent, like an immature fetal brain. As the brain grew, Muotri measured an increase in brain waves. At six months, the electrical system jumped from 3,000 spikes per minute in one neuron to around 300,000, a number no one had seen before in a brain organoid.

“I thought there must be something wrong. Maybe the electrodes were malfunctioning, or there’s a short circuit somewhere,” he says. When Muotri repeatedly observed the same data from different machines, he knew the brain waves were real.

Next, Muotri trained a machine-learning algorithm to measure the brain waves and compare them to data from 36 preterm babies obtained from hospital records. After nine months, the computer could no longer distinguish between data from a real human brain or a brain organoid. This demonstrated that the signal was very similar to that of a human brain.

Song thinks Muotri’s organoid is “a good start.” It is a far cry from an actual brain, he says, since it is so tiny and missing so many components, but it is still progress.

“This work really shows that the organoid has complex patterns of neural activity for future studies. They allow us to study whether (the brain waves) are altered in different diseases. We normally did not have access to study that,” Song says.

Muotri is already on to his next step, using the mini brains for autism research, and he is also launching a company to make the organoids for commercial use, such as testing new drugs. He says it is possible to create a brain organoid with nearly any disorder that has a genetic factor, such as autism. He does this by growing the organoid with cell samples from someone with autism, thereby running their genetic code in the organoid.

“This work really shows that the organoid has complex patterns of neural activity for future studies. They allow us to study whether (the brain waves) are altered in different diseases. We normally did not have access to study that.”

But don’t cue the creepy music, throw back your head, and scream, “It’s alive!” just yet. Without a bloodstream or body for support, the tiny organoid can never grow to a full-sized human brain. Still, the new territory floats ethical questions within the research community. Does the brain organoid have a consciousness?

“The features are similar, but I would not say there is a functional brain in a dish, or anything close,” Song says.

Muotri agrees. He says that the wad of brain cells is far from a bonafide brain, but there is promise in this direction. So Muotri is holding a meeting this fall to bring together scientists and ethicists to discuss the possibility of consciousness in brain organoids, now or in the future.

“I don’t want the society to have the wrong impression that we’re creating these brains that can think and talk to you. We’re definitely not quite there yet,” he says. But even Muotri plans to proceed with caution. “The ultimate goal of the research is to help millions and millions of people, like any other technology. I think it’s fair to stop, pause, and see where this is going. How far we can go?”