At first glance, it would seem like a satellite and a machine gun have little in common. One is clearly a weapon, while the other flies thousands of miles above our heads, relaying television programming or unlocking the secrets of the universe. There’s little chance of confusing the two.

However, for about 15 years, the U.S. government treated the two as the same. Specifically, both were considered munitions by the government, subject to strict laws known as International Traffic in Arms Regulations, or ITAR. That made it difficult to export them to even allied countries, and virtually impossible to many others.

How satellites, and components used to make them, became classified as munitions dates back to the 1990s. At the time, commercial satellites, like those used for communications, were subject to a less-strict set of export control regulations run by the Commerce Department. That allowed them to be exported to places like Russia and China to be launched from those countries, which offered less expensive launch options than companies in the U.S. or Europe.

In the mid-1990s, though, launch failures involving American-built satellites on Chinese rockets led to allegations that technologies on those satellites were improperly transferred to China. In response, Congress passed legislation that officially reclassified commercial satellites and their components as munitions, subjecting them to ITAR.

(C)ompanies…had to register, in effect, as arms dealers in order to sell satellites.

What that meant was that companies that planned to sell satellites to other countries, even to close allies in Europe or Canada, now had to go through a far more difficult licensing and approval process in the State Department, which administers ITAR. That included companies that had to register, in effect, as arms dealers in order to sell satellites.

The immediate reaction was a sharp downturn in satellite sales. Throughout the late 1990s, U.S. companies won about 80 percent of the commercial communications satellites ordered worldwide. In 2000, with those satellites now under ITAR, that market share dropped to about 50 percent, and stayed at that level, or even less, in the years that followed.

Those satellites are manufactured by major companies, including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Orbital Sciences Corp. (now Orbital ATK), who were used to dealing with ITAR for sales of fighter jets, missiles, and other items more widely recognized as munitions. Over time, they were able to adapt to the stricter regulations and continue to sell their satellites, although some markets, like China, were no longer available.

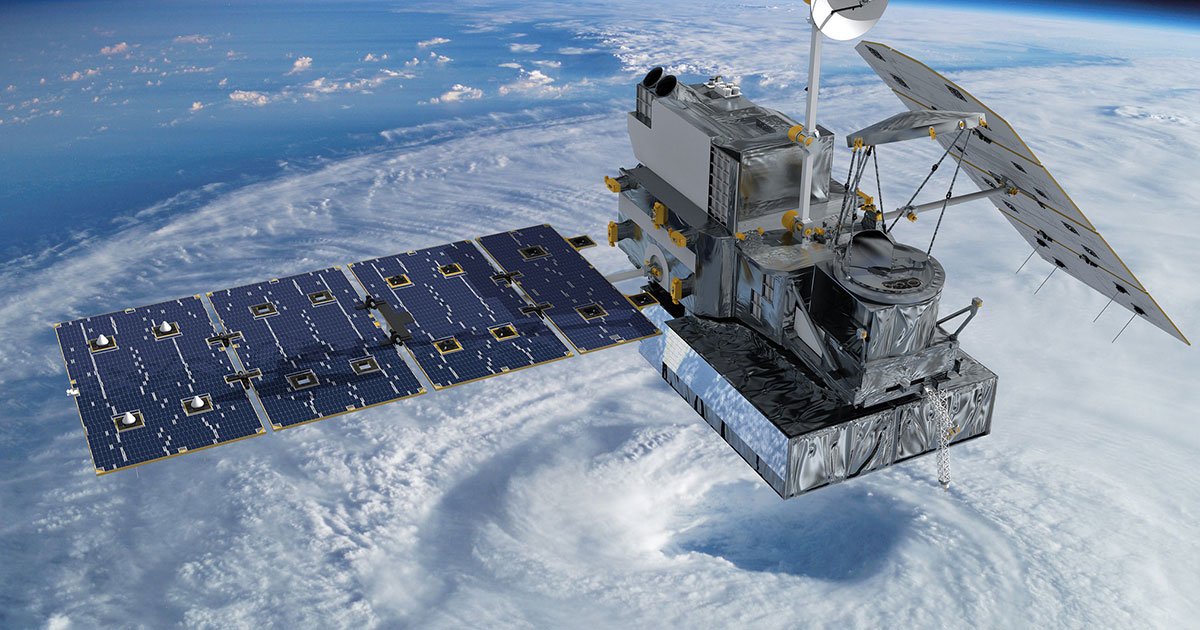

Smaller companies, though, were hurt harder by ITAR. These included companies that did not build satellites themselves, but instead provided components, like solar arrays, batteries, and computers used to build satellites. These companies, prior to the shift to ITAR, were able to sell their components not just to the major satellite manufacturers in the U.S. but also companies in other countries.

With those components now regulated by ITAR, many of these companies, unlike the bigger manufacturers, weren’t able to handle that change, not having offices full of export control lawyers and other specialists versed in handling the additional burden of complying with ITAR. Worse, the State Department itself wasn’t prepared for that additional workload, and as a result applications for licenses and other approvals languished, with companies losing business as a result.

Those consequences were unintentional, those who wrote the law reclassifying satellites and related components as munitions recalled. The intent, they said, was simply to cover the big communications satellites, but as written and ultimately interpreted by regulators, it included those components.

“I predicted that if we didn’t get this right, we’d really regret it. And I’m sorry to say that I was right: we didn’t get it right.”

“I predicted that if we didn’t get this right, we’d really regret it,” recalled David Garner, a retired Air Force officer who helped draft the original law, at a satellite industry conference in 2007. “And I’m sorry to say that I was right: we didn’t get it right.”

At the same time, the technologies the law was trying to protect were becoming increasing available in other countries. One European satellite manufacturer, Thales Alenia Space, advertised so-called “ITAR-free” satellites that contained no U.S.-built components, and that were free of export control restrictions from the U.S. That meant they could be exported to countries like China where no amount of ITAR paperwork would allow them to be shipped.

The satellite industry in the U.S., seeing lost business exporting satellites and components, and concerned that ITAR was actually giving other countries the motivation to develop their own satellite technologies instead of buying them from American companies, lobbied for years to try and undo that damage. They sought to move at least some satellite-related items outside of ITAR’s jurisdiction. The problem was that since an act of Congress moved those items under ITAR’s control, only an act of Congress could do the same.

After President Obama took office, his administration started an effort to review everything under ITAR, from guns to planes to tanks, choosing to take off from the munitions lists those items that were obsolete or widely available outside the country. It could not, though, review satellites and related components until Congress acted to give it that authority.

Finally, in late 2012 Congress passed a defense authorization bill that restored to the president the ability to move satellites and related components off the munitions list.

Finally, in late 2012 Congress passed a defense authorization bill that restored to the president the ability to move satellites and related components off the munitions list. That kicked off a long-awaited review of which items should remain under the control of ITAR and which should be moved back to the less restrictive export control list maintained by the Commerce Department, where commercial satellites were prior to the late 1990s.

By mid-2014, that work was largely completed. The State Department published an updated list of the satellite-related items under the control of ITAR, which went into effect late in the year. The good news for the satellite industry was that, finally, many commercial satellites and their components would no longer be subject to ITAR. They would still be subject to reviews, as well as a blanket prohibition from being exported to China.

Suborbital spaceflight technology also remains under ITAR out of concerns the technologies…could be repurposed for anti-satellite weapons.

There were some exceptions to that good news. The industry sought to get more commercial remote sensing satellites—those able to take high-resolution images of the Earth from space—off the ITAR, citing advances in similar satellites in other nations, but were unable to win over regulators. Suborbital spaceflight technology, like those being developed by companies such as Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic, also remains under ITAR out of concerns the technologies used for carrying people on brief trips into space could be repurposed for anti-satellite weapons.

Still, the industry has been largely satisfied with the changes. “It’s been a long time in coming,” Patricia Cooper, at the time the president of the Satellite Industry Association, an industry group that advocated for export control reform, said in 2014 when the final rule came out.

And while there are still some tweaks the industry would like to make to export controls, the situation is far better for them than what it was just a few years ago. Commercial satellites once again have little in common with machine guns.