This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

It takes nine months for a fertilized egg to develop into a roughly 7-pound baby, and during that time, the person carrying the baby gets to feel the miracle of life growing inside them. They can also expect to experience a slew of unpleasant side effects, from nausea and vomiting to breathing difficulties and back pain.

That’s during a normal pregnancy — in the US, about 8% of them include complications that threaten the health of the baby-carrier or fetus. Childbirth, meanwhile, is painful at best and fatal at worst.

Even when a pregnancy and birth is uncomplicated, the person who carried the baby is often left with lifelong changes to their physical and mental health — but what if technology could eliminate the need for anyone to go through pregnancy and childbirth to have a baby?

Artificial wombs

While a typical healthy pregnancy ends around 40 weeks, babies born after just 21 weeks in the womb have survived thanks to incubators, devices that keep prematurely born babies warm and safe until their bodies are developed enough to live outside the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

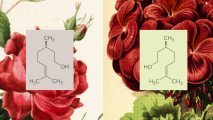

At the other end, in the beginning, embryos for in vitro fertilization (IVF) are typically grown in the lab for a few days before implantation. Researchers have even grown embryos outside the body for up to two weeks (and they could probably go longer).

Some scientists think we could take this a major step further, creating fully “artificial wombs” that provide the ideal environment from conception through gestation, eliminating the need to actually carry a baby inside the body.

This hypothetical process of developing a fetus outside the body is known as “ectogenesis,” and not only would it eliminate the many health risks linked to pregnancy and childbirth, it would also make biological reproduction available to people for whom it’s currently difficult or impossible.

A person who lost their uterus to cancer, for example, could have an embryo created in the lab, like in IVF, but implant it in an artificial womb for gestation, rather than using a human surrogate, which is an ethically fraught practice.

By eliminating the need for surrogacy, artificial wombs could also make it easier for gay couples to have biological children. Further on the horizon, if scientists can replicate their success creating embryos from the DNA of same-sex mice in people, any two people might one day be able to have biological children related to both of them.

Where are we now?

Artificial wombs would fill in the critical gap between IVF and incubators. They don’t yet exist outside of science fiction, but they’re getting closer to reality.

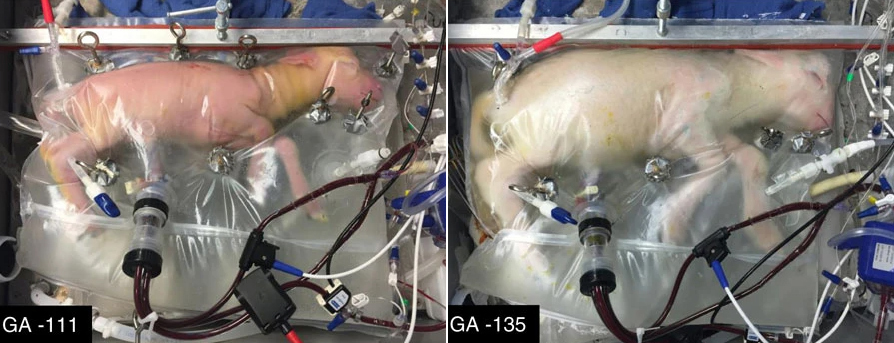

In 2017, researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia unveiled the “Biobag,” part of an artificial womb they are developing for prematurely born babies, known as EXTEND (“EXTrauterine Environment for Neonatal Development”).

Unlike incubators currently found in hospital NICUs, the Biobag is filled with lab-made amniotic fluid, the same liquid that surrounds a baby in the womb. Oxygen is added to the fetal bloodstream via a device attached to the umbilical cord.

“Fetal lungs are designed to function in fluid, and we simulate that environment here, allowing the lungs and other organs to develop, while supplying nutrients and growth factors,” said fetal physiologist and EXTEND developer Marcus G. Davey.

To demonstrate the Biobag, the researchers removed lamb fetuses from their mothers’ wombs at what would be the equivalent of 23-24 weeks in a human pregnancy — most human babies born at 24 weeks or earlier don’t survive, and those that do have a high chance of life-long health problems.

The animals continued developing for up to four weeks inside the Biobags, getting bigger, growing wool, and opening their eyes.

Members of the EXTEND team have since founded a startup, Vitara Biomedical, which has raised $100 million, from Google Ventures among others, to further develop the device and support its first clinical trial.

In September 2022, co-inventor Alan Flake presented some of Vitara’s latest achievements at the Philly Builds Bio+ Symposium, noting that the company had received Breakthrough Therapy status with the FDA, a designation that helps accelerate development. They’ve also shown that EXTEND can also now support pig fetuses — which are the same size as humans.

“We’re in the midst of pre-submission of it where we will submit an [investigational device exemption] hopefully in the near future, and hopefully, this will be a clinical reality in the not too distant future,” said Flake.

EXTEND isn’t the only womb-like device of its kind in development.

A group in Europe is working on the Perinatal Life Support (PLS) system, another artificial womb designed to give extreme preemies a better shot at survival. A team from Australia and Japan, meanwhile, is developing a platform called the Ex Vivo Uterine Environment (EVE) therapy, which has already been tested with premature lambs.

All of these systems are designed to act as a bridge between the natural womb and the outside world. When will we get a device that actually replaces the womb, and what would that look like?

Looking ahead

While significant progress is being made on replicating the conditions of the womb during the latter stages of pregnancy, we still barely even know what’s going on during the earliest weeks.

That’s partly because it’s very hard to observe what’s happening in the womb, and partly because research on human embryo development outside the womb was long prohibited beyond 14 days. At that point, scientists were required to dispose of the embryos, and if you couldn’t grow an embryo beyond the point where it’s still an undifferentiated blob of cells, you certainly couldn’t develop a system to keep a fetus alive for nine months.

In 2021, scientific regulators relaxed the 14-day rule, saying that longer development of human embryos outside the womb could be considered on a case-by-case basis.

That removed one barrier to the development of artificial wombs, but the scientific challenge of getting a human embryo to develop into a viable baby outside the body remains — scientists are still trying to figure out how to gestate mouse embryos in the lab past their halfway development point (which is only about 11 or 12 days).

Even if scientists are able to overcome the scientific hurdles and create artificial wombs capable of supporting humans across the full nine months of development, society might reject them.

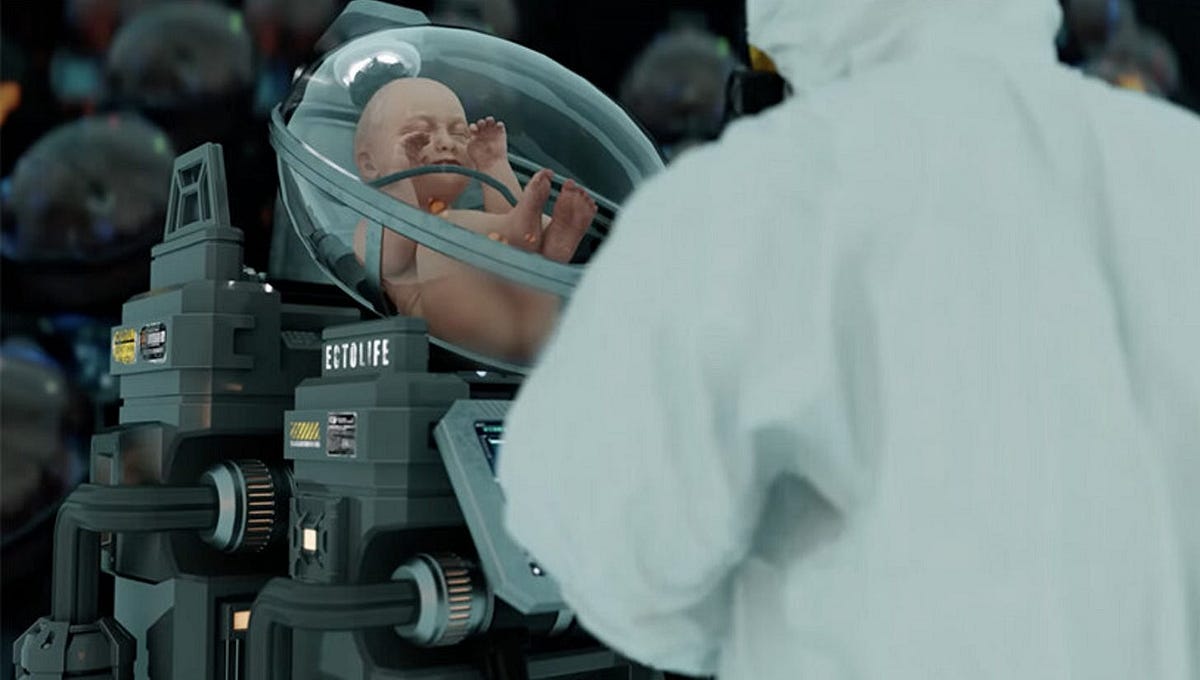

In December 2022, biotechnologist and film producer Hashem Al-Ghaili released a short film depicting EctoLife, a fictional factory where hundreds of babies could grow in artificial wombs. Many mistook the concept for reality and lashed out against it as “scary” and “dystopian.”

We’re a long way from baby factories, but if artificial wombs ever do come to fruition, the social backlash against them could prove temporary — IVF was once considered scary and unethical, too, but today, it’s largely accepted.

Ultimately, concerns about the ethics of growing babies in artificial wombs will need to be weighed against the very real physical and mental trauma of human reproduction today and the challenges of infertility. If technology could potentially free people from that, is it unethical not to pursue it?

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].