Getting children to take medicine is notoriously difficult — they often balk at the taste of liquid meds and downright refuse to swallow pills or tablets. For parents of kids who need to take medicine every few hours, it can be a daily struggle.

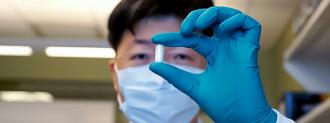

Researchers at MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital were trying to develop a better way for children to take medicine — and ended up creating a weird new drug delivery system, which could help with everything from diabetes to obesity.

Targeting the Intestinal Lining

When you take a drug orally, it travels through your GI tract, where it’s broken down and absorbed into the bloodstream. Most of this absorption takes place in the small intestine, so the researchers behind the new drug delivery method targeted that organ.

“We recognized its potential,” researcher C. Giovanni Traverso said in a research brief. “If we could specifically target this location, it would open up new avenues for drug delivery and nutritional modulation.”

They began by developing an adhesive that would stick to the intestinal wall, experimenting with a sticky polymer that helps mussels latch onto rocks.

The next problem was getting this polymer (called polydopamine) to line the small intestine. For a proof-of-concept study, they decided to take advantage of the body’s natural chemistry.

The small intestine is home to an enzyme called catalase, which can break down hydrogen peroxide to release oxygen. Oxygen, meanwhile, causes the hormone dopamine to assemble into polydopamine.

By combining liquid dopamine with a bit of hydrogen peroxide, the researchers created a substance that could enter the digestive tract and travel all the way to the small intestine, where catalase enzymes will transform it into polydopamine. There, the substance would stick around for about 24 hours, before being shed, just like the cells that normally comprise the intestinal lining.

Once in place, this intestine-lining goo could deliver drugs, proteins, or enzymes exactly where they are needed, all day. It could also help solve nutritional problems, like inability to digest certain foods (like lactose) or limit the absorption of excessive glucose, which can cause diabetes and obesity.

The fact that it remains in place for a whole day is what makes the system potentially useful for children — instead of having to coax a child to take a medication every few hours, for example, doctors would just need to administer it once daily.

Drinkable Drug Delivery System

The researchers tested their creation, dubbed the “gastrointestinal synthetic epithelial lining” (GSEL) system, in pigs and rats, as well as on samples of human GI tissue.

In pigs, they found GSEL could deliver an enzyme that helps combat lactose intolerance. They could also modify GSEL to block the absorption of glucose in the small intestine, suggesting its future use as a treatment for diabetes or obesity.

They also tested the system in pigs as a delivery method for a drug used to combat parasitic flatworms.

The drug delivery system could decrease the number of doses needed to treat a disease.

Usually, a person (or pig) would need to receive this medication three times a day, but they found that GSEL greatly extended the amount of time the medication remained in the body. If delivered via GSEL, a patient would only need one dose a day, which could be useful when medicating young patients.

For the pig experiments, the researchers put GSEL directly into the animal’s small intestine, but they’re now working to make the system fully ingestible, either as a liquid or a pill.

There’s still a lot of research to be done before human trials, but GSEL has tremendous potential as a drug delivery system for patients both young and old.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].