Researchers from The Tisch Cancer Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have presented results of a new antibody-based therapy for blood cancer — and the results are very good.

The therapy, which uses a specific type of antibody, was successful in eliminating or reducing markers of the cancer in 73% of multiple myeloma patients across two different studies: a phase 1 trial, which led to two recommended doses, and a phase 2 trial, which tested those doses.

All of the patients had already been treated with at least three different therapies, showing the drug has efficacy against even the most intractable cases of multiple myeloma.

“This means that almost three-quarters of these patients are looking at a new lease on life,” Ajai Chari, the director of clinical research in the Multiple Myeloma Program at Tisch and lead author for both studies, said.

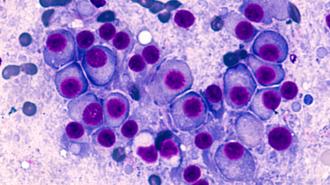

Multiple myeloma is a cancer of the plasma cells, white blood cells that dwell within the spongy marrow of your bones and crank out antibodies to protect against infection.

A deadly disease: Multiple myeloma is a cancer of the plasma cells, white blood cells that dwell within the spongy marrow of your bones and crank out antibodies to protect against infection.

The cancer occurs when such cells proliferate out of control — cancerous cells then crowd out the blood cell making cells they share the marrow with, reducing the number of healthy blood cells in the body, and produce junk antibodies which do not fight pathogens.

The American Cancer Society estimates that there will be 34,470 new multiple myeloma cases in 2022, and 12,640 deaths; of these, the majority will be in men. The overall 5-year survival rate in the US is 55%.

While myeloma can be attacked with the usual arsenal — surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy — it has a nasty tendency to come back, at which point it is called “relapsed multiple myeloma.” If a patient’s myeloma resists known cancer treatments, it is deemed “refractory multiple myeloma.”

The high rates of relapse and acquired resistance make new myeloma therapies desperately needed.

The high rates of relapse and acquired resistance make new myeloma therapies desperately needed.

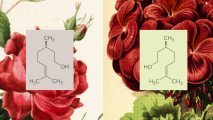

Calling in the cavalry: The Tisch team’s new therapy candidate, called talquetamab, poetically uses the body’s own immune system — the very one myeloma corrupts — to attack the cancer.

Unlike other immunotherapies, which pull immune cells out of the body, train them to target cancer, and return them to the body, their approach instead uses a specific type of antibody, called a bispecific antibody.

Infused into the body, one part of the bispecific antibody sticks to the myeloma cells, while the other part binds to T cells — the soldiers of the immune system. By sticking to both, the antibody brings the cavalry right to the enemy.

The results: The phase 1 trial enrolled 232 patients at cancer centers across the globe. Between January 2018 and November 2021, the patients received multiple different doses, either intravenously or via injection beneath the skin (future trials will solely focus on the latter method).

After a median follow-up of just under a year, 70% of patients in the lower-dose group responded to the treatment, while 64% in the higher-dose group responded. “The median duration of response was 10.2 months and 7.8 months, respectively,” according to the study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The therapy uses a specific type of antibody, and was successful in eliminating or reducing markers of the cancer in 73% of multiple myeloma patients across two different studies.

The just released phase 2 trial saw 143 patients receive a lower dose of the therapy weekly, with a higher dose administered biweekly to another 145 patients. Across both groups, the response rate was around 73%, Chari said, with that response holding strong for all subgroups, except for a subset of rare cases where the multiple myeloma has invaded organs and soft tissues.

Of those who responded, over 30% of patients had no measurable myeloma markers, while nearly 60% had their cancer signatures significantly reduced, although not fully eliminated. The median duration of response is, so far, just over nine months.

The phase 2 results were presented at the American Society of Hematology’s annual meeting December 10.

“Talquetamab induced a substantial response among patients with heavily pretreated, relapsed, or refractory multiple myeloma, the second-most-common blood cancer,” Chari said.

While talquetamab is the first to use its specific antibody target, it is not the only bispecific antibody on the scene; the FDA has recently approved Johnson & Johnson’s Tecvayli, which uses the same basic method to fight multiple myeloma.

The Mount Sinai study was sponsored and funded by Janssen, which is owned by J&J.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].