Access to experimental stem cell therapies like the kind we profiled in Reversing Blindness could soon disappear due to pressure from the Food and Drug Administration, which has proposed new regulations that would effectively shut down private stem cell clinics in the U.S.

The regulatory battle over stem cells reflects the divide between doctors who think stem cells are safe and effective and those who think more research is needed, as well as the increasing urgency facing patients with hard-to-treat diseases and little or no effective options. In a rather unusual move, the FDA followed the release of its draft guidelines with hearings in Bethesda, Maryland, held earlier this week. Over the course of two days, dozens of patients, clinics, and doctors gathered to debate the merits of the proposed new regulations. (Normally, regulatory bodies post proposed regulations online and accept comment on the regulations in written form only. The FDA has said that holding a public event to discuss these regulations is highly unusual and a direct response to intense interest from stakeholders in the stem cell debate.)

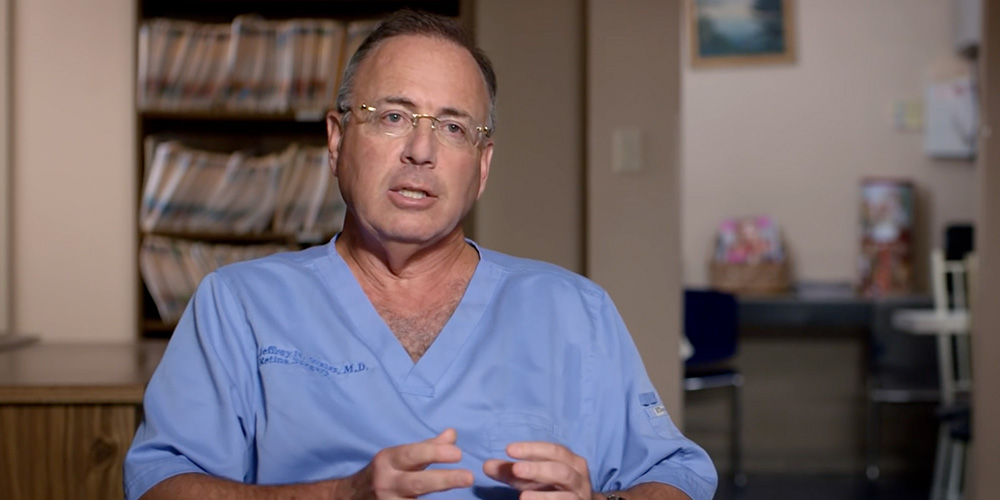

One of the doctors who attended the hearings was Dr. Jeffrey M. Weiss, formerly of Harvard and MIT, who is conducting a Stem Cell Ophthalmology Treatment Study (SCOTS) at his private clinic in Florida. (Dr. Weiss was recently profiled in an episode of Superhuman.) When we last spoke to Dr. Weiss, he said he’d treated nearly 400 blind or partially blind patients, and that roughly 60 percent have experienced improved or restored eyesight following a procedure in which he extracts stem cells from patients’ bone marrow, and injects the cells into patients’ retinas and optic nerves. Some patients are then placed in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber, which increases the oxygen level of their blood in order to expedite healing.

But Dr. Weiss has his critics. And those critics have their own critics. If you watched our episode on Vanna Belton and Dr. Weiss, and wanted to know more, this article will help you make sense of the debate over the procedure that restored Vanna’s eyesight. If you haven’t watched the episode, you should! And then read on.

So, what do we know about stem cells?

Researchers have found that stem cells can do lots of things: They can “transdifferentiate,” or become different types of cells, which is theoretically why stem cells from one part of the body can be injected into a completely different part of the body and still live. They also have a “paracrine” effect, which means they influence the cells surrounding them to grow, repair, and multiply. And they can reduce inflammation. The fact that stem cells can do all these things is why researchers on both sides of the stem cell treatment debate are excited about them.

In clinical trials, adipose-derived stem cells have increased the success rate of reconstructive surgery grafts, and bone marrow-derived stem cells have helped “fully halt all detectable CNS inflammatory activity in patients with multiple sclerosis for a prolonged period in the absence of any ongoing disease-modifying drugs.”

The debate: whether stem cells should be treated like prescription drugs

Currently, stem cells derived from a patient’s own body–called “autologous” stem cells–aren’t considered pharmaceutical drugs so long as the cells are used the way the body would naturally use them and aren’t significantly altered in a clinical setting. That means autologous stem cells derived from fat tissue–the type used in most private clinics–are regulated the same way as fat deposits used in cosmetic and reconstructive surgery.

But in December 2015, the Food and Drug Administration alerted stem cell therapy providers that fat-derived stem cells would no longer be covered under the rule for body tissue used in more conventional surgical procedures. In a letter to clinics, the FDA claimed that because stem cells derived from fat tissues are administered like a drug (which is to say, via an injection) and are marketed as helpful in the treatment of multiple disorders (ranging from M.S., to joint pain, to impaired vision), they’re technically a “biological drug.”

In short, the FDA is saying that taking fat tissue from a person’s abdomen and injecting it into their lips, either to repair them or enhance them, is not analogous to using stem cells extracted from fat tissue to cure an illness.

But the distinction is not just semantic, because even though we know more about stem cells today than we did yesterday, there are stem cell researchers who think we don’t know enough.

The case for treating stem cells like drugs

Advocates for tightly regulating stem cell therapies say there’s simply not enough data.

(Critics) argue that…it’s potentially misleading and perhaps even dangerous to offer expensive stem cell therapies to patients.

And they argue that because there’s no clinical trial data showing that stem cells can be safely and effectively used for a large variety of diseases, it’s potentially misleading and perhaps even dangerous to offer expensive stem cell therapies to patients. The potential danger lies not necessarily in the surgical procedure itself–though one death case in the U.S. allegedly resulted from a now de-licensed doctor injecting bone-marrow fragment into a patient’s circulatory system–but in not knowing what transplanted stem cells will do over time: unlike actual drugs, they don’t simply “pass through” the body, but stay alive and multiply in the injection location.

Critics wonder what long-term effect a new cell type could have in a different location within the body. If you’re of the opinion that stem cells need more vetting, knowing that some stem cells have worked in a few small trials for a handful of diseases is not enough information to say that stem cells can be used to treat the large number of diseases for which stem cell therapies are currently marketed.

But there’s also an argument that stem cells are a surgical procedure, and don’t need regulation

(P)roviders argue…that it’s a surgical procedure, which isn’t a field of activity that the FDA regulates.

Many stem cell therapy providers argue that because the procedure simply involves taking tissue from one part of a person’s body and moving it to another part of their body, that it’s a surgical procedure, which isn’t a field of activity that the FDA regulates. The obvious parallel is plastic surgery. If a person has third degree burns on their arm, but not on their leg, a plastic surgeon isn’t prohibited from using a leg skin graft to replace arm skin, nor are they required to demonstrate that the two types of skin are identical at the cellular level. Nor is that burden in place for procedures in which fat is removed from one part of the body and used to create volume in another part of the body. But that’s exactly the kind of burden the FDA is considering imposing on stem cell therapies.

That’s part of the argument made by Elliot Lander, co-founder of the Surgical Cell Network, in his op-ed for the California Healthline.

And let’s not forget that the fight over stem cells could leave patients in limbo

Even critics of unregulated stem cell therapies see promise in the research. That’s why many of these same critics are pushing for not just regulations, but clinical trials.

The thing is, patients don’t want to wait, and many of them say they can’t. SammyJo Wilkinson, who suffers from muscular dystrophy and co-founded the patient rights group Patients for Stem Cells, had her own stem cells extracted and then cultured by a clinic in Texas. “When therapy is needed,” Wilkinson wrote in an op-ed about how stem cell therapy helped her go into remission from MD, “the pure (adult mesenchymal stem cells) are expanded in their lab to a therapeutic dose, similar to university clinical trials.”

But in 2012, the FDA ruled that growing new stem cells–as opposed to using stem cells that have been extracted and then re-injected without adulteration, the method that’s being challenged by the latest round of regulations–do in fact count as a drug, and Wilkinson was forced to go to Mexico to continue receiving stem cell therapy. After four treatments, Wilkinson writes that she’s been in remission since 2014.

Stories like Wilkinson’s, as well as those of Vanna and another patient of Weiss’s named Doug Collins, are why so many patients flooded the FDA with requests to speak at this week’s hearings. Unregulated stem cell therapies might be incredibly expensive, or ineffective, or even dangerous. But that’s also true of approved drugs available to patients with incurable diseases. Not every treatment works on everyone, every drug has side effects, and even drugs covered by insurance can be expensive.

(P)atients don’t want to have wait 10 to 20 years for regulatory approval, and they certainly don’t want to be forced to travel outside the U.S. for a shot at a miracle.

For patients whose only options are something known and insufficient, or something unknown and potentially effective, they don’t want to have wait 10 to 20 years for regulatory approval, and they certainly don’t want to be forced to travel outside the U.S. for a shot at a miracle.

Should patients settle for a middle ground?

C. Randall Mills, the head of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and another speaker at the FDA’s hearing this week, argues that federal regulators need to create a middle path between the decade-long, billion-dollar process for biological drug approval and the current environment, in which no stem cell therapy is subjected to any regulation. “The regulatory burden associated with one is massive and the other is almost nonexistent,” he writes in an op-ed for California Healthline.

“I would rather know these clinics are being regulated and collecting data than have them operating under the radar screen of the FDA,” Mills writes. “I would like there to be a formal pre-market review of these therapies before they’re put on the market. I would like there to be safety and efficacy data.”

“If you’re a patient who has absolutely no alternative, you’re probably willing to take the chance.”

Want to read more about the debate over stem cell therapies?

For patients with multiple sclerosis considering stem cell therapy, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society offers a list of questions patients should ask when considering stem cell treatment.

Paul Knoepfler, a stem cell researcher and advocate for FDA regulation of stem cell therapies, has also published a patient’s guide.

“Myths and Misconceptions about Stem Cell Research,” from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

The FDA’s proposed new rules for stem cell therapy can be found here.