What if there were missiles that are deadly when shot at your enemies but harmless when they hit your allies? That would be a game changer when it came to warfare — allowing one side to dominate the other.

It turns out they already exist and are being used to fight a microscopic battle.

Researchers at Berkeley Lab want to use bacteria-made nanomachines to help fight enemy cells in the human body. The powerful nanomachines are proteins called tailocins.

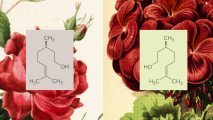

“They’re like a spring-powered needle that goes and sits on the target cell, then appears to poke all the way through the cell membrane making a hole to the cytoplasm, so the cell (…) collapses,” Vivek Mutalik, a research scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, said in a statement.

A wide range of bacteria strains can produce tailocins as a defense mechanism against other bacteria. But they are a suicide attack. When the pointed nanomachines eject through a bacteria’s membrane to target the enemy, it destroys itself as well. However, once released, tailocins only target specific bacteria strains — enemy strains. It leaves the rest of the host lineage’s bacteria unaffected.

“They benefit kin but the individual is sacrificed, which is a type of altruistic behavior. But we don’t yet understand how this phenomenon happens in nature,” said Mutalik.

Tailocins are an area of major interest for microbiologists because of the potential ways to harness their selective combat abilities.

One possibility is that, instead of antibiotics, tailocins could be used to fight bacterial infections. Antibiotics wipe out beneficial bacteria strains in addition to harmful ones, and they are also losing their effectiveness because of evolving drug resistance. But tailocins would only target the bacteria causing the infection, leaving friendly microbes unscathed.

To determine how bacteria use tailocins to fight for survival, the researchers compared the genetic differences between tailocin producers and the enemy bacteria strains they target. They also explored the physical mechanisms regulating how tailocins target and attack specific strains.

“Once we understand the targeting mechanisms, we can start using these tailocins ourselves,” said Adam Arkin, co-lead author on the paper, published in Nature.

After looking at 12 soil bacteria strains, they found that differences in the fat and sugar-based molecules attached to a bacteria’s outer cell membrane play a role in determining if a specific tailocin targets a strain.

In the future, Mutalik, Arkin, and the rest of the team hope to get a closer look at the action — by filming the process at the atomic level. They plan to use the advanced imaging facilities at Berkeley to follow the attack from the moment the tailocin attacks the enemy bacteria cell until the enemy cell completely collapses.

“The potential for medicine is obviously huge, but it would also be incredible for the kind of science we do, which is studying how environmental microbes interact and the roles of these interactions in important ecological processes, like carbon sequestration and nitrogen processing,” Arkin said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].