This article is an installment of The Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

Electricity transformed the world by making many innovations possible, like new appliances and faster communication. Superconductivity could do it all over again — if physicists could only figure out how to make it practical.

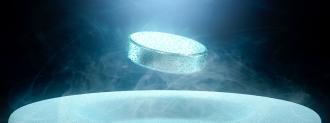

Superconductivity happens when a material stops resisting an electric current — in other words, it’s friction-free electricity. Materials that facilitate this easy, resistance-free flow are called superconductors.

5% of the electricity generated in the U.S. is wasted in transmission and distribution, costing consumers billions of dollars each year.

Electricity is generated when electrons flow from one atom to another. Right now, daily life is powered by electricity that has to overcome a lot of resistance. This resistance causes typical conductors — like copper wiring — to lose energy every time an electron moves. This inefficiency comes in the form of released heat.

You can blame this resistance every time your laptop overheats, when those batteries run out of juice, and when your light bulbs burn out. It’s also why 5% of the electricity generated in the U.S. is wasted in transmission and distribution, costing consumers billions of dollars each year.

But if we used superconductors (materials that don’t lose energy when electrons move around) then all of our electrical devices — or entire electric grids, for that matter — would get a serious efficiency upgrade.

Ice, Ice Baby

We actually have some superconductors, today. Most are used in powering body scanners in hospitals, like MRIs.

But superconductivity today depends on cooling the material to extremely low temperatures, most times to sub-freezing. For obvious reasons, this isn’t practical for cell phones or personal computers.

If we want to unlock the widespread commercial potential of superconductivity, we’ll need to raise the thermostat. For decades, scientists have been on the quest for superconductivity that can happen at room temperature.

Late last year, they found it.

Gettin’ Hot in Here

In October 2020, scientists at the University of Rochester announced that they achieved superconductivity at just 58°F, in a material composed of hydrogen, sulfur, and carbon. Previously, the highest recorded temperature for superconductivity had been a mere 8°F in 2018.

“In 10, 15 years, we probably will be seeing a different world.”

Ranga Dias University of Rochester

In just two years, the science went from operating at a risk-of-hypothermia temperature to a nice, balmy fall day.

Ranga Dias, a mechanical engineer who led the research, told Vice this was a game-changer.

“This can really flip the whole world in terms of the technology we’re using right now — that’s why I think so many researchers are putting their full effort to make this a reality,” said Dias.

“In 10, 15 years, we probably will be seeing a different world.”

Under Pressure

Achieving room-temperature superconductivity is a huge feat — but there’s a catch, which is almost as big as the temperature problem.

To achieve superconducting at such high temperatures, Dias and his team had to apply pressure — lots of pressure. They had to squeeze the material to 267 gigapascals, or more than 2 million times the Earth’s atmospheric pressure, according to ScienceNews.

“People have talked about room-temperature superconductivity forever,” Chris Pickard, a materials scientist at the University of Cambridge, told Quanta Magazine. “They may not have quite appreciated that when we did it, we were going to do it at such high pressures.”

This high-pressure requirement will keep room-temperature superconductivity in the lab, for now.

Future of Superconductors

Now, scientists are on a quest to find a superconductor that can operate at room temperature and ambient pressure.

Scientists are using computer calculations to guide their search. These calculations help determine the structure and properties of the material they’re looking for, according to ScienceNews.

Finding such a superconductor would open up many commercial options that seem like only a dream to us right now: MRIs could become more powerful and could help doctors diagnose diseases earlier, quantum computers could be commercialized, and almost all of our electrical devices would become faster and have a longer lifespan.

Paul Chu, the founding director and chief scientist of the Texas Center for Superconductivity at the University of Houston, told Vice the science has enormous potential.

“I think if you can stabilize this high pressure state, you can change the world.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].