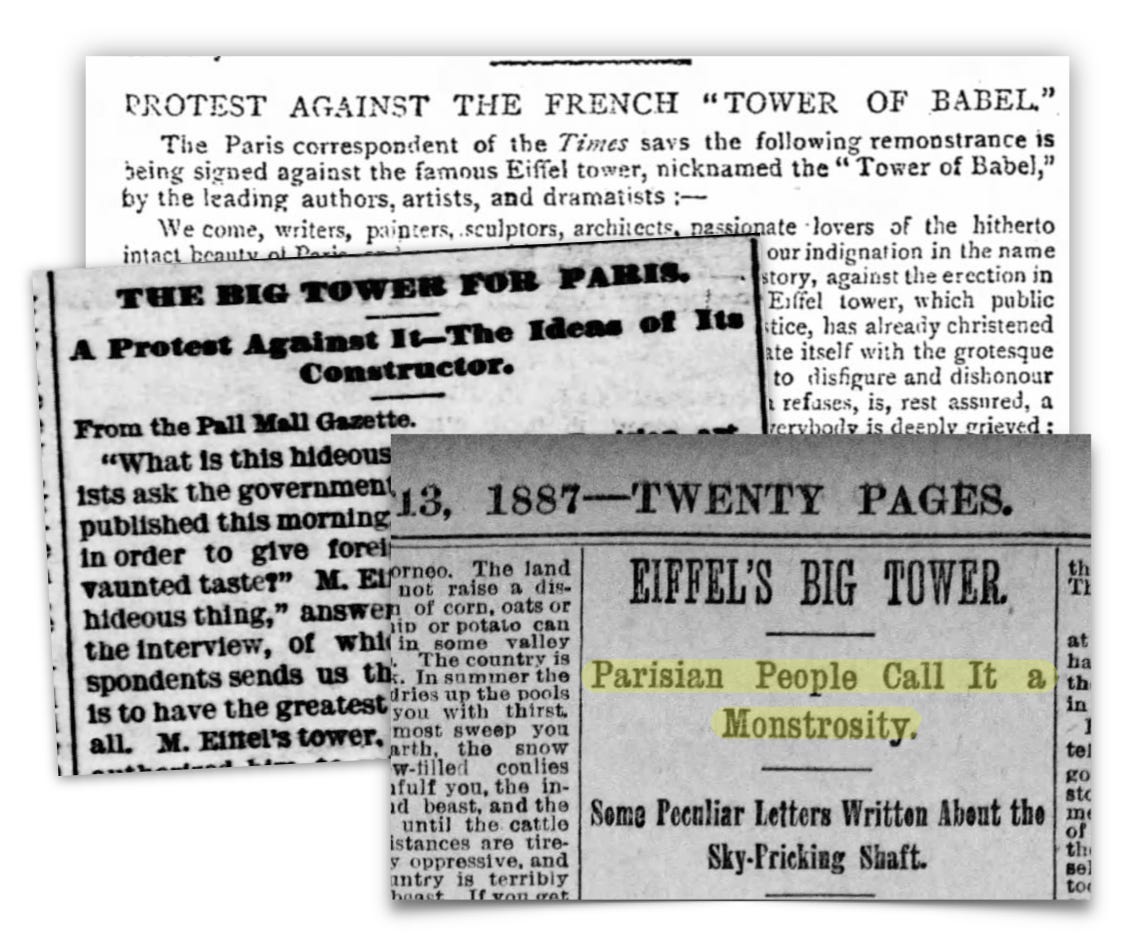

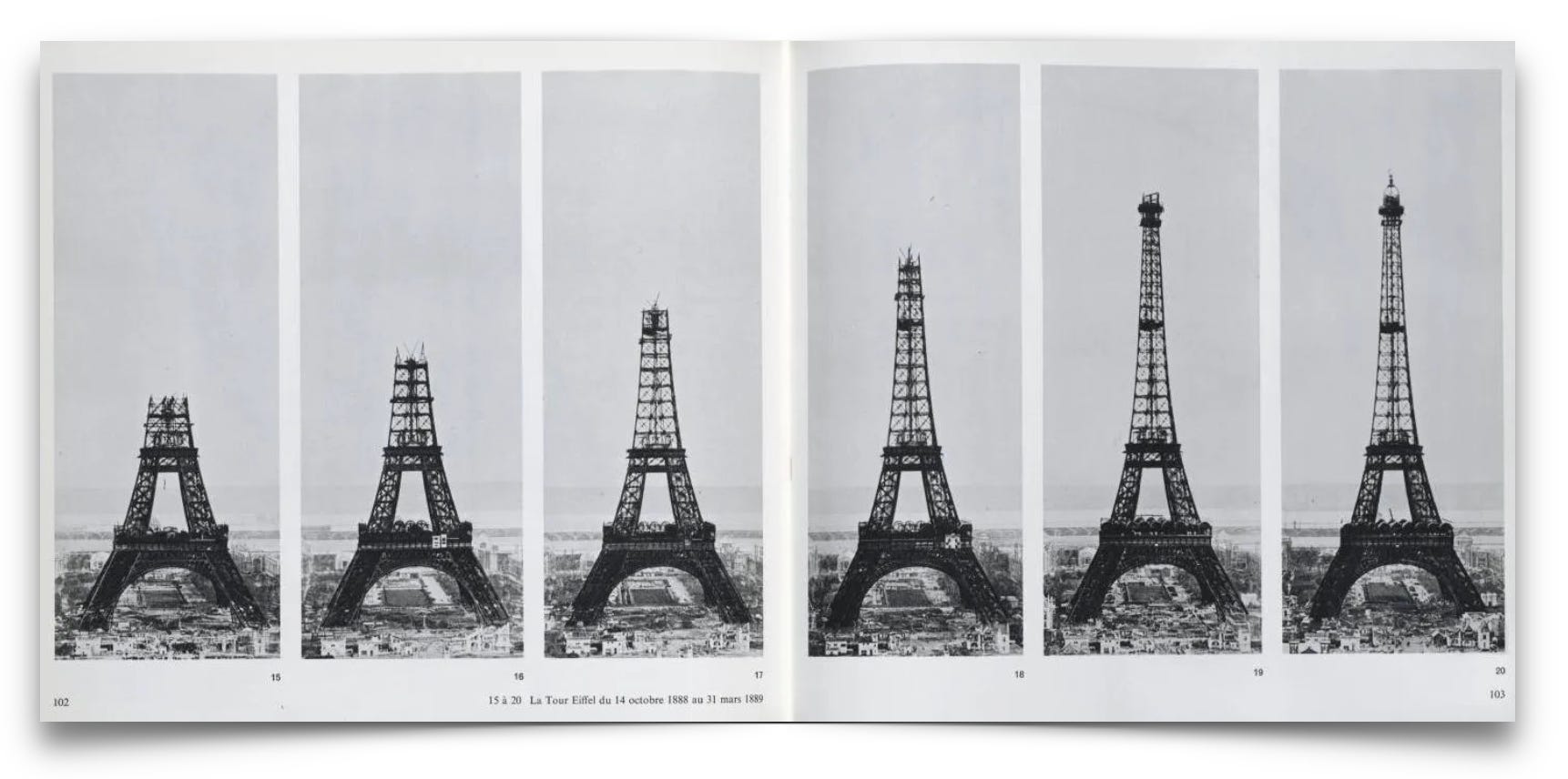

The Eiffel Tower is as iconic of France as croissants and baguettes and equally emblematic of Paris as Notre-Dame or the Arc de Triomphe. Yet, before completion for the 1889 World’s Fair, the project was treated by some as an industrialist “Tower of Babel” that was anti-ethical to French taste and culture.

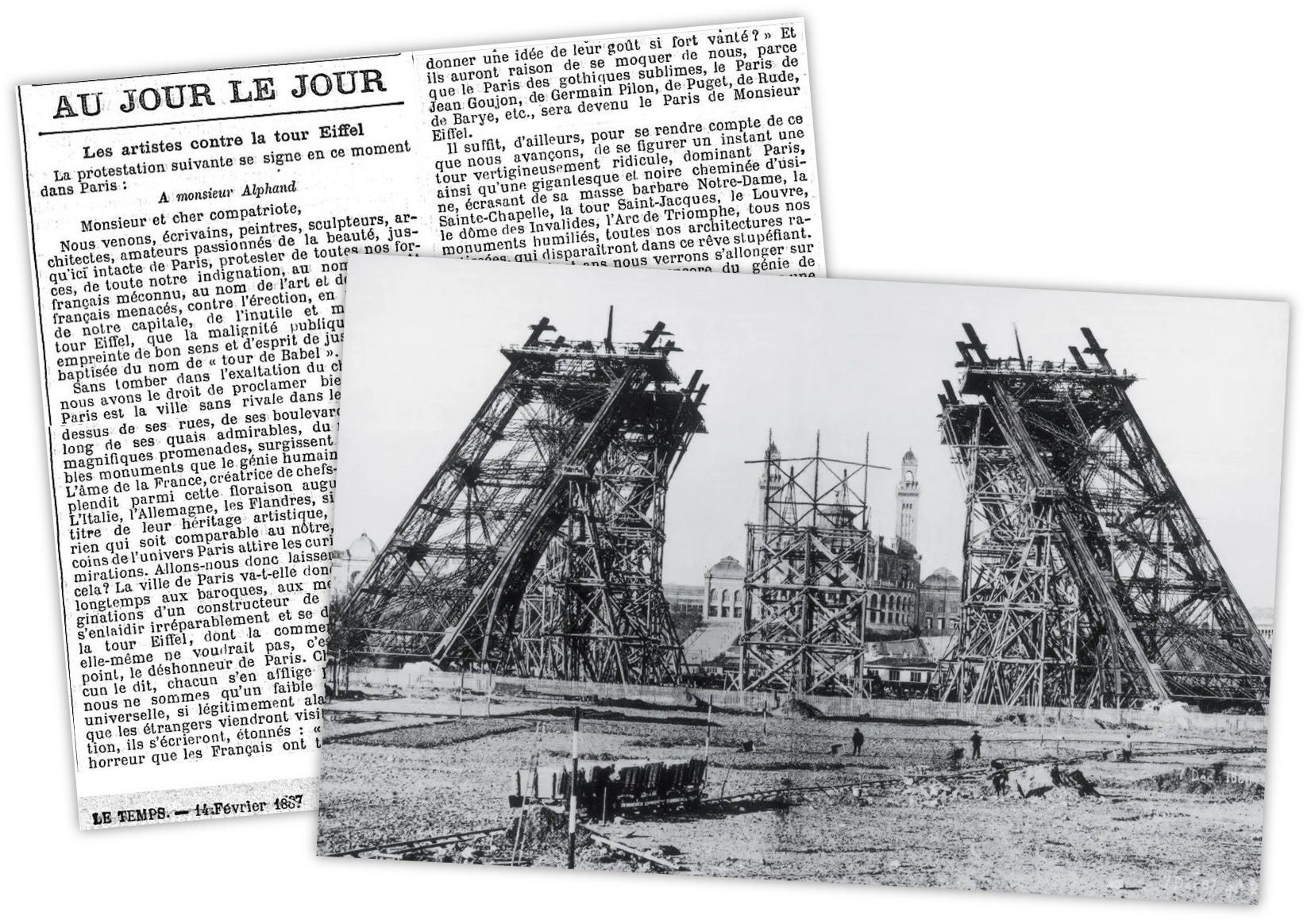

A month after construction began in 1887, a group of prominent French artists published an open letter, titled “Artists against the Eiffel Tower.” It was featured on the front page of Parisian newspaper Les Temps.

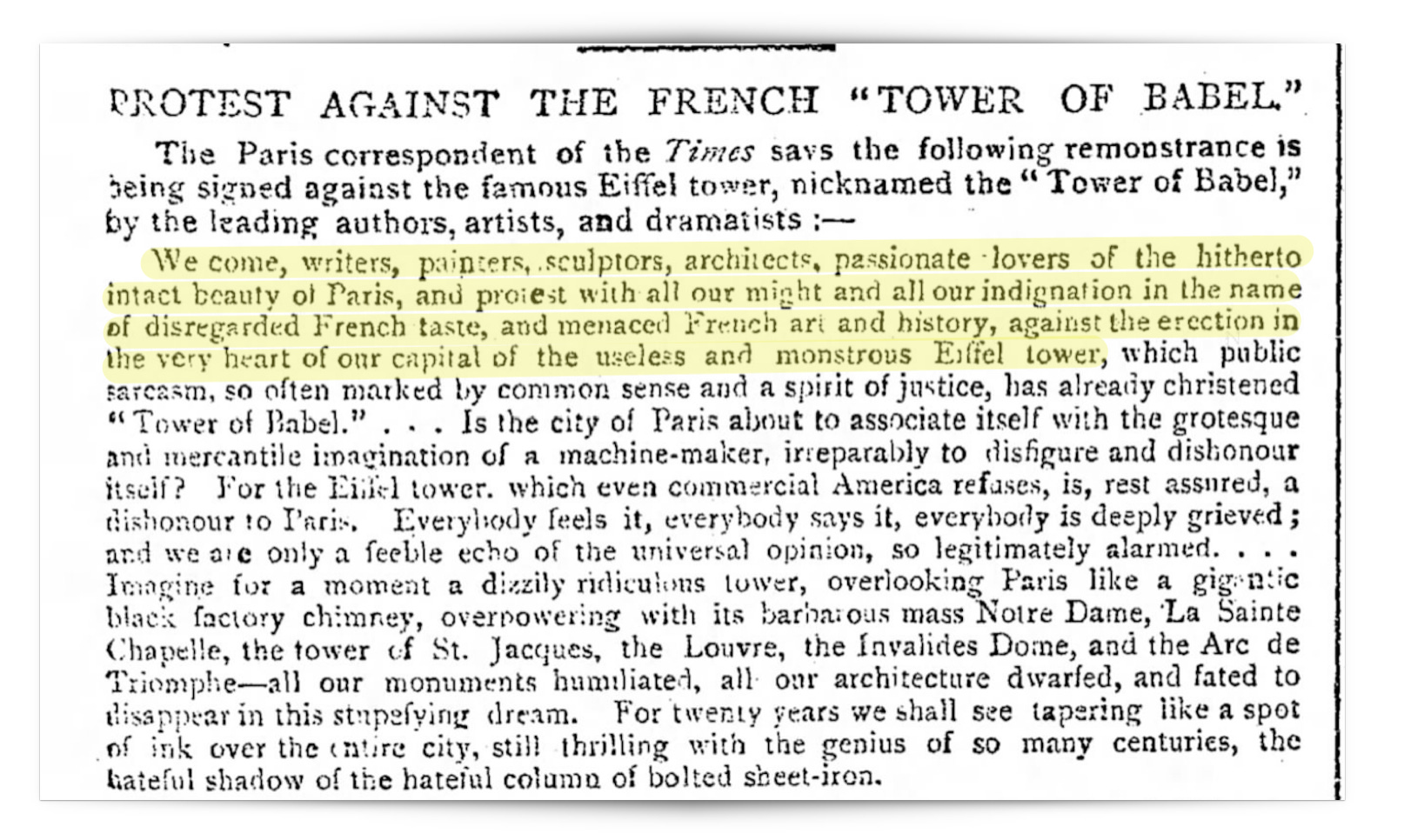

The letter, signed by some of the greatest creative minds in France, implored that the project “menaced French art and history” and called the tower a “useless and monstrous” structure, which would “irreparably disfigure and dishonour” Paris.

The entire text, translated from French, can be read and heard here.

Its authors claimed this “dizzyingly ridiculous tower” would overshadow Paris’s iconic monuments, like Notre Dame and the Arc de Triomphe, leaving all Parisian architecture “humiliated” and “dwarfed” in the “shadow of this odious column of bolted sheet metal.”

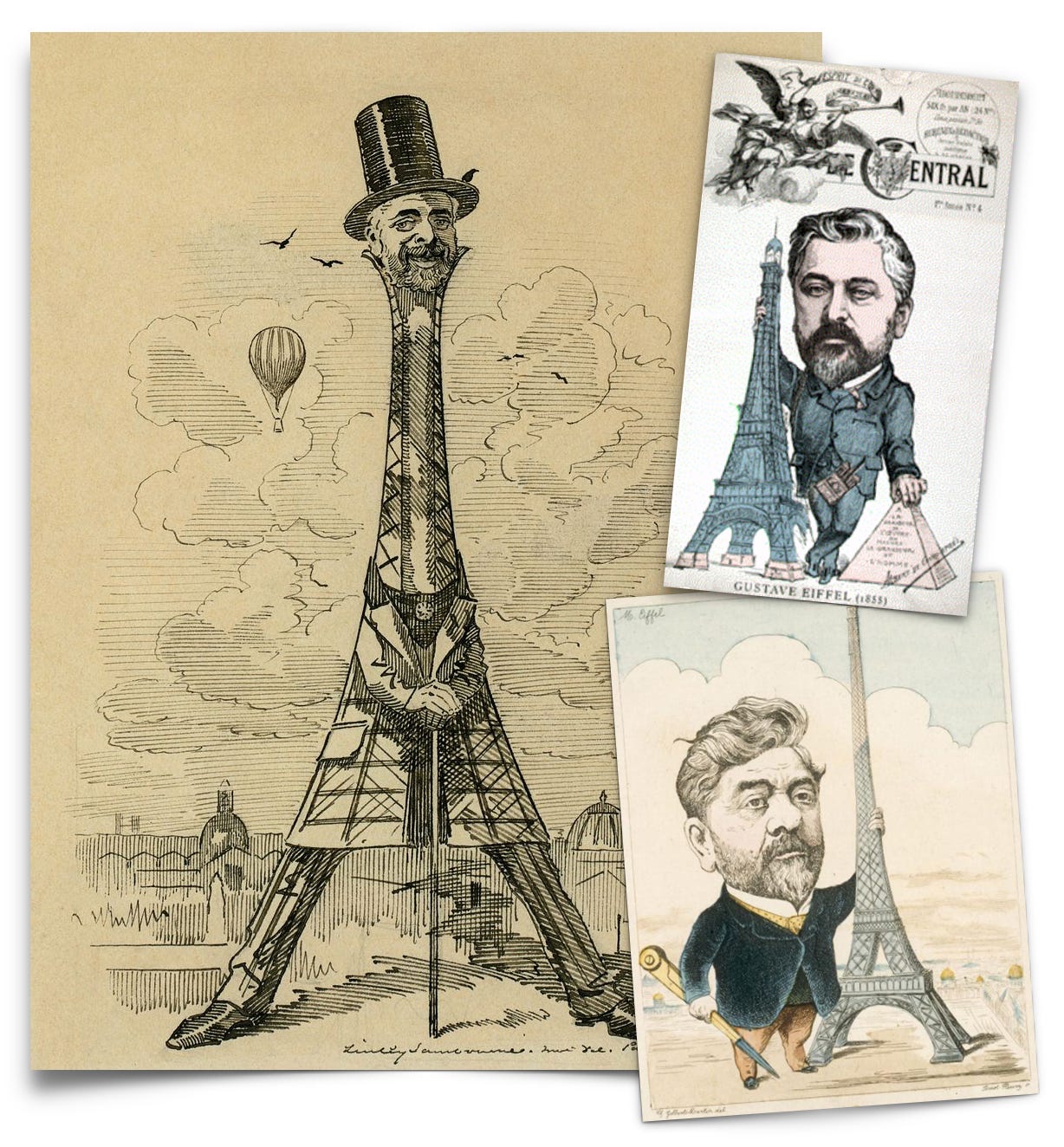

To these artisans, the project was “industrial vandalism,” a “stupefying dream” from the “grotesque and mercantile imagination of a machine-maker.” They were, of course, referring to Gustave Eiffel — the tower’s designer and namesake.

One source of contempt for the project was that Eiffel, an engineer, won the contract to build his tower over venerated architect Jules Bourdais, who had initially proposed a tower made of stone, more fitting with Parisian architecture.

The official Eiffel Tower site describes this tension:

The two projects were total opposites: stone versus iron, an architect versus an engineer, classic versus modern… The battle took place in the press, with Eiffel and Bourdais mobilizing their respective supporters.

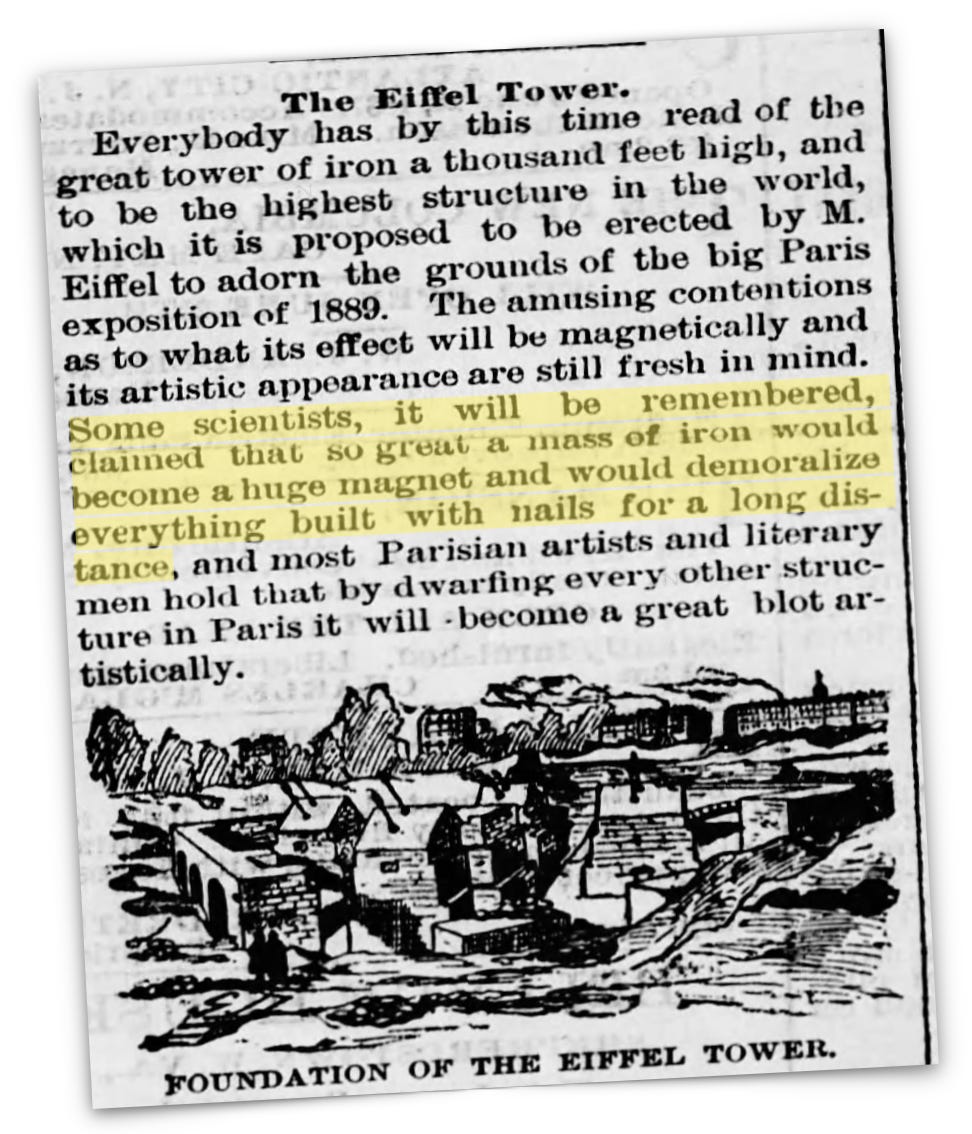

Opponents of Eiffel sowed concerns that the structure — soon to be the largest tower in the world — would collapse in high winds. Some scientists were even purportedly concerned that the iron structure might magnetize everything in France — that would, in turn, “demoralize everything with nails for a long distance.”

Monsieur Eiffel’s defense

Eiffel did not care for his critics and would defend his vision with gusto in an interview in the very same issue of Le Temps the letter of protest appeared. He’d say of the project, “There is an attraction in the colossal, a special charm, to which the ordinary theories of art are not applicable.”

Eiffel would note that the Pyramids of Egypt were not aesthetic feats, but engineering ones that inspired the world. “Why should what is admirable in Egypt become hideous in Paris?” Eiffel would ask rhetorically. This, in turn, would see him painted as arrogant and delusional. Cartoons would caricature him as such.

Ridicule would not be confined to France. The Boston Globe would write, “The bare idea of a cast-iron tower of that height is terrible” and that models of it “do not mitigate the terrors of imagination.” A British newspaper would write if construction went ahead, France “will soon be the proud possessor of the biggest and ugliest Tower the world has ever seen” — a move that would prove Parisians had “lost the capacity of distinguishing between the sublime and the ridiculous.”

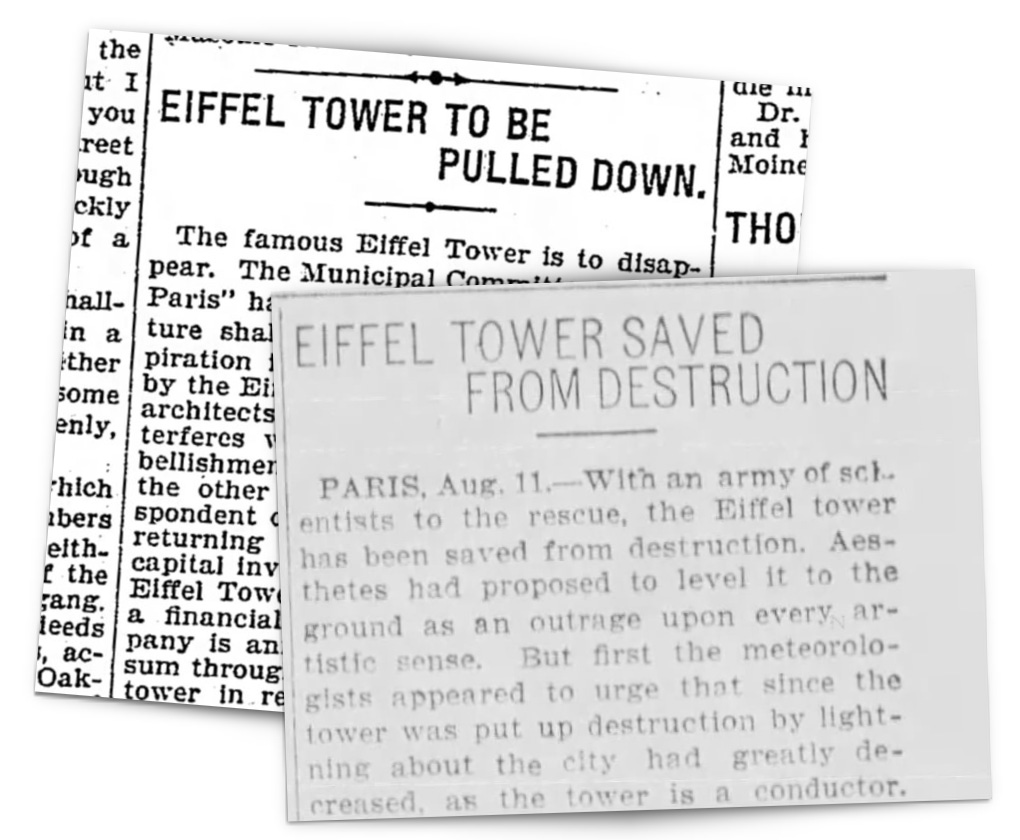

What makes the strident opposition to the Eiffel Tower even more amusing is that the whole thing was only meant to be temporary — after 20 years, it was due to be deconstructed on December 31, 1909. Those old opponents of the tower worked to ensure this would happen, but Eiffel pushed back, to extend its presence.

Eiffel won — again — with scientists, astrologers, meteorologists, and military leaders all coming to the tower’s defense for its practical uses for their professions. The Eiffel Tower is now a permanent fixture of Paris, and its namesake is now more associated with Paris and French culture than any of its high-profile detractors.

This article was originally published on Pessimists Archive. It is reprinted with permission of the author.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].