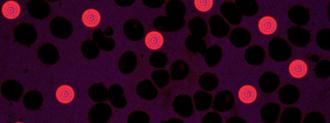

A tiny sponge disguised like a red blood cell can cruise the bloodstream, unnoticed, for a long time.

“It is an artificial particle, but to the outside world, it looks like a red blood cell, and it behaves like a red blood cell,” says biomedical engineer Jordan Green.

Green’s team at Johns Hopkins University created the imposter by shaping a plastic nanoparticle into a blood cell and dressing it in a cloak made out of a real cell membrane. Once injected into the body, the “invisibility cloak” tricks the immune system into thinking the mimic is one of the body’s own cells, so it won’t get attacked.

Disguised, the mimic can travel through the bloodstream, soaking up lethal toxins like a sponge.

Red blood cells carry oxygen to the body from the lungs. But they also have another important role: removing toxins from infections. Such chemicals are sometimes created by the body to fight infection, but too much poison in the bloodstream could overwhelm the system and cause sepsis, a deadly malady.

Increasing the number of red blood cells, real or fake, could speed up the recovery time from toxin-related conditions. Green wondered if he could design a mimetic particle that acts like a dummy blood cell. Would it soak up toxins, then be cleared from the body by the immune system, possibly saving lives?

“We can learn from nature and bio-inspired materials,” he says.

The nanosponge evolved from previous work in this field of research that used round particles. But Green wanted it to look more like a red blood cell because “modeling technologies after something that occurs naturally could have better outcomes.” He decided a sphere wasn’t the right shape and settled on trying two forms: a football, and a frisbee.

Taking their cue from nature, they designed their nanosponge to have the same look and feel as a real cell. They used a biodegradable polymer called PLGA, which is often used in sutures or stitches and dissolves on its own. They stretched the sphere-shaped particles into an elongated shape that matches red blood cells. Then, coated it in the same skin — a mouse’s red blood cell membrane — to trick the body into thinking the mimic belongs.

To test the sponging ability, Green injected the nanosponges into mice who were infected with a lethal dose of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. They found that the football-shaped copycats circulated 600% longer than the uncoated, round version, before eventually being digested by the immune system.

Mice that were not treated with the nanosponges died within several hours of being infected, whereas half of the treated mice survived long-term (meaning, in a mouse study, more than one week after treatment). The work is published in the journal Science Advances.

“The effect was striking,” Green says, explaining that the spherical sponges coated with a membrane prolonged the mouse’s life by a few hours. But it was only with the different shapes that mice survived long-term. Green found that the football-shaped nanosponge could flow through the blood vessel best, lasting longer and soaking up more toxins.

“Designing the surface to match the biology, and designing the particle and its physical properties to match the biology — when you put it together, it’s dramatically stronger,” Green says. He adds that their next effort is to match the elasticity of the material with a red blood cell, which is very flexible.

Dennis Discher, a biophysical engineer at the University of Pennsylvania, who does not work with Green, agrees that the research is promising.

“It adds great clarity to earlier findings that particle shape affects cell-particle interactions and circulation in vivo,” Discher says. “The coating of particles by red cell membranes is also an intriguing strategy.”

Designing the particle and its physical properties to match the biology — when you put it together, it’s dramatically stronger.

Jordan Green

In the future, the tiny sponges could be used as an emergency treatment. For example, if a soldier on a battlefield was attacked with a toxin, then a quick injection of a serum containing the nanosponge could soak it up, possibly saving their life. Green says it could work well for just about anything that red blood cells naturally soak up, but he could also engineer it to be more specific. Plus, he could add a medicine at the core, which could be released once the nanosponge dissolves.

Given the ongoing social distancing orders, a lot of Green’s lab is currently closed down. But despite much research being paused, Green says that he is working on using the nanoparticle technology to create a coronavirus vaccine. Unlike the nanosponges, these particles won’t be hiding from the immune system, but flagging it down to stimulate antibodies against the virus.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected]