This year, an estimated 100,000 people in the U.S. will be diagnosed with melanoma, a rare but aggressive form of skin cancer — and even if they beat it, they’ll be at a high risk of developing melanoma again.

That might not always be the case, though, as a personalized skin cancer vaccine developed from patients’ own tumor cells has shown promise in a very small trial, involving eight melanoma survivors.

“We found evidence of everything we look for in a strong, sustained immune response,” study co-leader Patrick A. Ott said in a press release.

Vaccinating Against Cancer

Vaccinating someone for something they’ve already had might seem strange — the purpose of a COVID-19 vaccine, for example, is to train our immune system to spot and kill the coronavirus before it causes an initial infection.

Cancer is a different beast, though. It causes our own cells to mutate, and those mutated cells then grow aggressively.

To vaccinate against specific cancers, we need to train the immune system to attack cancer cells without harming healthy cells.

That’s harder than training it to attack an obvious intruder, like a bacteria or a virus, and it’s also not possible until the person actually has cancer — only then will we know what their specific cancer cells look like.

But once we have sequenced a patient’s tumor, we can try to develop a vaccine for it that trains the immune system to attack those cells — and only those cells.

Personalized Skin Cancer Vaccine

NeoVax, the personalized skin cancer vaccine at the center of this new study, was developed by researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Broad Institute.

To create the vaccine, the researchers collected tumor cells from eight patients who’d recently had surgery to remove melanoma.

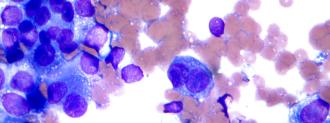

Tumor cells have proteins called neoantigens on their surfaces. Those proteins serve as a red flag to the immune system, letting it know that the cell is cancerous and should be attacked.

Sequencing the DNA of the cancer cells identified a specific part of the tumor’s neoantigens, called an epitope, which T cells target when fighting cancer.

Researchers then used each patient’s epitopes to create a personalized skin cancer vaccine for them, which they administered when each recipient was about 18 weeks out from their melanoma surgery.

Four Years Later: A Robust Response

In the years since, patients have been giving regular blood samples to check their immune response, and on January 21, researchers published the first results in the journal Nature Medicine.

According to the paper, the T cells not only showed evidence of remembering the epitopes in the personalized skin cancer vaccine, but had also learned to recognize other melanoma-related epitopes.

We found evidence of everything we look for in a strong, sustained immune response.

Patrick A. Ott

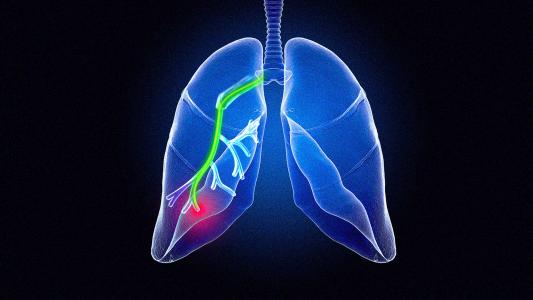

While all eight patients are still alive and six are disease-free, the cancer did spread to the lungs of two of the participants during the course of the study.

Those patients were treated with a type of drug called an immune checkpoint inhibitor, and the researchers found evidence that their vaccine-trained T cells had gotten inside the tumor tissue — their most lethal vantage point for fighting cancer.

“The long-term persistence and expansion of the melanoma-targeting T cells is a strong indication that personal neoantigen peptide vaccines can help control metastatic tumors, particularly when combined with immune checkpoint inhibition,” Ott said.

Looking Ahead

While the results of this study are promising, we’re still years away from being able to deliver a personalized skin cancer vaccine to every melanoma survivor.

For one, we’ll need much larger trials to draw any hard conclusions about NeoVax’s effect on the immune system. Those trials could tell us whether it actually prevents melanoma recurrence long-term, too — right now, we just know it creates a robust, durable immune response. How useful that immune response is remains to be seen.

The vaccine also took the researchers about three months to make, and while they don’t reveal the cost that went into that, it likely wasn’t cheap — in 2016, immunologist Robert Schreiber told STAT a single personalized cancer vaccine would cost an estimated $60,000.

If researchers can find a way to quickly and cheaply produce effective personalized skin cancer vaccines at scale, though, the shots could potentially save thousands of lives every year.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].