Jordan Riley’s memory of the day he died is surprisingly good. He can remember the test he was supposed to be studying for instead of playing flag football; running across the middle of the field and leaping for a pass, feeling someone plow into his knees, and seeing the sky above his feet; the sound the back of his head made as it smashed into the ground; trying — and failing — to snap the fingers of his left hand as he walked off the field; dragging his left leg through the grass as his vision began to dim.

And finally, he can remember telling a woman with a phone to call an ambulance because he’d suffered a brain injury.

Everything after that is blank. Because shortly after hitting his head during that intramural football game in April 2009, Jordan Riley was brain dead.

When the neurosurgeon reviewed his CT scan, he found Jordan had suffered an acute right cerebral holohemispheric subdural hematoma. Basically, the impact from hitting his head had caused a blood vessel in his brain to burst. The blood had then pushed his brain sideways inside his skull, and jammed his brain stem down.

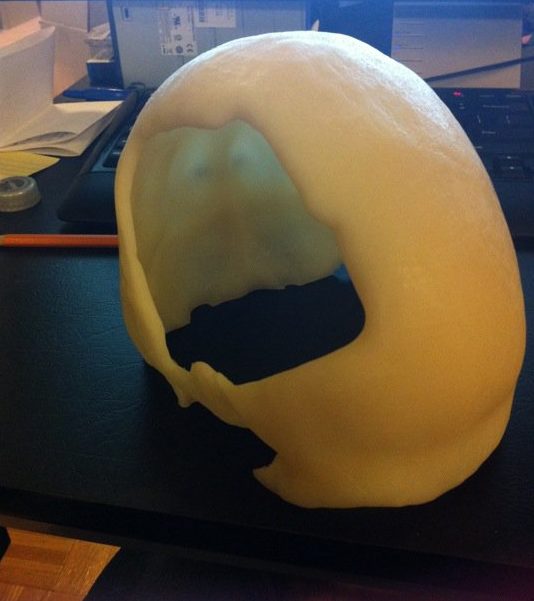

Everything the neurosurgeon knew about the human brain generally, and Jordan’s case specifically, suggested there was nothing he could do, and he wrote as much in his physical exam notes: “The patient has suffered a likely catastrophic injury to his brain.” But because Jordan was only 23, and otherwise healthy, the surgeon decided to operate. They wheeled Jordan’s body — which at this point was entirely reliant on life-support machines — into an OR, and removed roughly a third of his skull in an attempt to relieve the pressure. They placed the removed piece of skull inside Jordan’s abdomen to keep the bone alive, and crossed their fingers.

Seven hours later, Jordan woke up.

Within a day, he was able to use an alphabet board to communicate with his family.

Within three days, he was walking.

After 10 days, they reattached his skull, and within a few months, he’d taken his finals — albeit without a time limit — and received his college degree.

But Jordan wasn’t OK. He just didn’t know it yet.

Jordan and his family knew at least some things didn’t work like they used to. For instance, he took several cognitive functioning tests before leaving the hospital. One test required him to look at a list of four words and identify the one word that was categorically different from the others. Another test required him to name all the words starting with “S” that he could think of. Not only did he fail to identify the ill-fitting word, but over the course of 45 seconds, he was able to name only one word that began with the letter “S.”

“We just assumed it was something that would pass and that I’d be back to new soon enough,” Jordan says. “The mindset within the family was almost to treat the brain injury as any other sports injury that heals with time.”

Jordan himself contributed to this belief, albeit unintentionally. To graduate with his bachelors in accounting from Florida State University, he needed to pass the final exams for five upper-level accounting classes. The school allowed him unlimited time, and though he spent roughly four hours on each test, he passed all of them and was able to graduate, and then land an entry level accounting job.

Doing something that big obscured how hard it was to do the little things. “One to two months after the injury, I remember listening to a friend, thinking I was doing a good job of following them,” Jordan says. “Then, when they paused to get a response out of me, I literally could not recall a single word that was said.” Another time, he spent an hour wandering through a parking lot looking for his car only to remember that he’d walked to the store.

These incidents, and thousands of others, reflected the specific locations of his injury. The damage to his brain stem diminished his ability to construct new memories, retain information, or focus his attention for more than a few seconds; while the damage to his right frontal lobe made it practically impossible to understand the emotions of others, or relate to how they were feeling.

To his family and friends, Jordan seemed a little forgetful and distant. But for someone who’d been brain dead for nearly two hours, during which time the hospital encouraged Jordan’s brother to let them harvest his organs, he was doing remarkably well.

In reality, Jordan was cut off from the world outside his head, and the world inside it.

His life reached a tipping point a few months into his new job. Week by week, Jordan had noticed his responsibilities dwindling, until finally his only task each day was to cold call potential clients using a script. Then one day, his supervisor told him what everyone else at the company already knew: Jordan had been so incompetent at the most basic accounting tasks that his colleagues were spending extra time at the end of the day redoing his work.

“I felt like someone punched me in the gut,” Jordan says. “I really honestly thought I had somehow come back from the dead just for the purpose of being stripped of all the mental gifts I hadn’t utilized and punished for my lack of motivation and drive.”

“I really honestly thought I had somehow come back from the dead just for the purpose of being stripped of all the mental gifts I hadn’t utilized and punished for my lack of motivation and drive.”

The revelation sparked a weeks-long spiral of drinking binges and depression. During one of those binges, Jordan ended up hitting his head and had to be admitted to the hospital. That’s when he had an epiphany: He was supposed to be dead, but wasn’t; perhaps he should figure out how to make the best of it.

In the spring of 2010, Jordan applied to participate in the Rusk Brain Injury Day Treatment Program at New York University’s Langone Medical Center, widely recognized as one of the most effective brain rehabilitation programs in the country.

“I went up to New York and walked into a community room with 15 or so people in it. I sat in front and the group introduced themselves to me. I found out that nine people there had brain injuries and the comfort I felt is really indescribable. I had been fighting in the dark against something that was messing with my brain for so long. I thought I was alone, but here were nine other people who got it. I can’t emphasize how important the discovery I wasn’t the only person dealing with this stuff was.”

“I had been fighting in the dark against something that was messing with my brain for so long. I thought I was alone…”

The Rusk program is small, and getting in is difficult. After four days of tests, Jordan returned to Florida to wait for an answer. A month later, he received an acceptance letter and a packet explaining exactly what was wrong with his brain. “My memory was in the 7th percentile, and my recall was in the 14th percentile.”

In the fall of 2010, he moved to New York and began rehab: Each therapy cycle was six months, during which he was at NYU Monday through Thursday, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. He did cognitive exercises and participated in group sessions with other brain injury patients. “It’s community based, meaning we all work together and share experiences. One, it lets us provide differing viewpoints on our injuries, and two, it lets people know they aren’t the only ones with problems. That comfort is really what allowed me to take all the protective layers off myself and address the issues I was facing.”

By fall 2011, Jordan’s sister, who’d moved to New York to help him in the rehab program, had returned to college. And that meant Jordan was living alone for the first time since his injury. But living alone wasn’t enough. He wanted to try having a job again, and begged the Rusk program to transition him into a “work trial,” during which he’d have a part-time, unpaid job at NYU. He ended up in NYU’s finance IT department.

“I won’t lie, it was scary initially…But working felt so good after years of sitting on the sidelines.”

“I won’t lie, it was scary initially because my last experience in an office had gone so poorly. But working felt so good after years of sitting on the sidelines.”

It was in that role Jordan discovered something about himself: While he couldn’t work for hours on end or consistently do calculations by hand, he had a knack for writing macros in Excel that would do the work for him.

“For some odd reason when I was engaged and trying to solve a problem within a couple lines of code, or designing a new process, I didn’t get tired as easily as I usually did. So instead of working like everyone else, I set about learning how to automate my workload where possible, ensuring it was accurate, and also preserving my energy.”

But there was a problem: The program permitted him to work only two hours a day. Initially Jordan worried that would be too much, but it ended up not being enough. Working in Excel energized him, so he started writing macros for a few hours before bed each night. He proved so good at it that the finance IT department offered him a paid position with benefits, and two hours a day turned into five.

It took several years, but Jordan had found a new groove.

Today, Jordan is the director of business analytics at one of the country’s largest insurance companies, and regularly visits NYU to speak to participants in the Rusk program about his own recovery. I met Jordan a few years before his injury, and we’ve spoken at least once a month since he started his rehabilitation. After watching our episode on OpenBCI — whose co-founder suffered a severe concussion during a rugby game — I asked Jordan if I could tell his story, and if he would share some of the strategies he talks about when he visits TBI survivors at Rusk. He kindly obliged.

1.) Learn something that makes you feel useful

“The worst thing about a brain injury before the recovery is that no one depends on you for anything. No one’s going to ask you to remember anything, or ask for your help, or expect you to solve a problem. You feel like the world doesn’t need you. When I found out that my colleagues at the first job I had after my injury were working overtime to fix my mistakes, that was crushing. I couldn’t do an entry level job and didn’t even know it without being told.”

“I needed to feel useful and to matter, but I also knew I couldn’t sustain accuracy for any long period of time in an office setting. I ended up getting obsessed with Visual Basic, because by learning it, I figured I could automate tasks and make myself valuable. I started Googling stuff and learned to code in Excel. Even learning really basic Excel functions made me feel useful, and now it’s basically my job.”

2.) Find someone who knows what you’re going through, and push each other to get better

“At Rusk, I was paired up for our rehab drills with an older guy who was really competitive. And I’m super competitive, too. The drills weren’t complex — the average person wouldn’t find them challenging at all — but it felt good to try and beat someone, to feel like a winner, to talk shit. I sucked at everything, but he did, too, and it felt fun just to compete again. That had been really important to me growing up — competing athletically and academically. The drills are insanely hard for people with brain injuries. But with him there, I could be better than someone, and he could be better than someone, and that brought out the fight in both of us.”

3.) Meet people who made a comeback

“During my time at Rusk, there was a guy who came to speak to our rehab program who ‘made it.’ After his injury and his rehab, he got married and had a kid. By the time I met him, I’d been injured for two years and I didn’t know what was possible. Really, nothing felt possible. Then I met this guy, and I could not tell that he’d ever been hurt. And it made me believe it was possible to be something like normal, or to pass as normal.”

4.) Believe you can get better

“Before I started at Rusk, I had to take a bunch of tests measuring my cognitive function, and I still have this 45-page packet of results lying around basically saying, ‘You suck.’ My memory was in the 7th percentile, and my recall was in the 14th percentile. I couldn’t remember what I ate the day before. I couldn’t remember where I put things. I couldn’t remember conversations. One time, I spent 30 minutes looking for my Xbox controller, gave up, and went to get something out of the fridge. The Xbox controller was in the fridge.”

“One time, I spent 30 minutes looking for my Xbox controller, gave up, and went to get something out of the fridge. The Xbox controller was in the fridge.”

“I also couldn’t focus. At the part-time office job I had while I was at Rusk, if I was working on something and someone was having a phone conversation in the next cubicle, I literally could not do anything because I couldn’t deal with hearing and thinking at the same time.”

“One of the first drills required us to sit in front of a computer and a program would make a ‘click’ noise every second for nine seconds. I was required to hit the computer’s spacebar when the 10th click was supposed to be. Then the program would click eight times, and I would have to make the nine click and the 10 click. The first time I did it, I clicked two-and-a-half seconds late.”

“Everything felt impossible, but I kept doing it, and you know what? It still felt impossible. But then one day it wasn’t. It’s like going to the gym. Other people notice you changing before you notice you’ve changed, but that doesn’t mean you’re not changing.”

5.) Speaking of: Don’t stop doing the things that make you better, because you will definitely get better

“Visual Basic did not make sense to me at all when I started it. But I kept using it, and over time, it started to feel like an actual language. It was like a flip switched in my head. I was looking at raw code one day, and I had this epiphany about how to use that data to build this proprietary piece of technology for our company. That wouldn’t have been possible without immersing myself in it and being kind of relentless.”

6.) Move around

“I work at a computer but I still average 12,000 to 15,000 steps a day, because it helps me think. I put instrumental music on, and I think about how my day went, about problems I couldn’t solve at work. The way memory works is that you see or hear something, and if you deem it important, your brain starts rehearsing it, which helps the memory stick. Just walking around without being in front of a computer is a great way to rehearse things and help them stick.”

7.) Be conscientious about things that don’t become habitual

“A lot of things become habitual if you do them often enough, and that’s even true for TBI survivors. The computer stuff, weirdly enough, has started to become habitual. But for me, there are things I still have to remind myself to do, like make eye contact when I’m talking to people and ask them questions. For a long time, I would talk to people forever who were not interested in talking to me, but I had no idea, so I have to remind myself to pay attention. What are they doing with their hands, with their eyes? Do they shift their weight when we talk? Do they look away?”

8.) Be more than your injury

“When I talk to people in brain injury rehab, they ask me if I still see myself as brain injured. And the answer is ‘No, I feel like me.’ And I say that because it’s very easy to feel defined by your injury. It permanently changes who you are, and it’s super easy to let that fact dominate your life and your attention. But people make the mistake of reducing themselves to the injury. It’s all they are to themselves and other people, is brain injured. I know I’m still dealing with it, but I’ve come to see that as just part of who I am, not the whole thing. Sometimes I have to take naps, because I run out of mental gas pretty easily. But I just see that now as within my normal human range.”

Homepage and feature image from Flickr