A small study has found that deep brain stimulation appears to help people with binge eating disorder control their food intake and lose weight — offering new hope to the millions of people living with the disorder.

The disorder: People with binge eating disorder frequently consume large amounts of food while feeling like they can’t control their eating.

As a result, many are overweight or obese, which raises their risk of many health problems, including heart disease, diabetes, and certain types of cancer. They’re also at higher risk of depression and other psychiatric illnesses.

Why it matters: Binge eating disorder is the most common eating disorder in the US, affecting at least 3 million people, and while therapy and medically supervised diets can help some regain control over their eating and lose weight, it doesn’t work for everyone.

Medications that can alleviate the symptoms of binge eating disorder, meanwhile, can be habit-forming or trigger serious side effects.

The treatment disrupts the brain signals linked to cravings for specific foods just before binges.

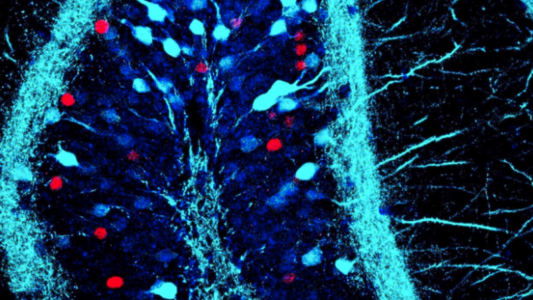

The idea: People with binge eating disorder experience cravings for specific foods just before binges, and in 2017, researchers discovered distinct electrical activity in a part of the brain called the “nucleus accumbens” right before these cravings — but not before non-binge eating.

When those researchers used deep brain stimulation to disrupt this electrical activity in the brains of mice prone to obesity, the animals ate significantly smaller amounts of a particularly tasty food than they would have without the stimulation.

What’s new? Scientists at Penn have now taken that research into humans, testing the ability of deep brain stimulation to reduce disorder-associated food cravings in two severely obese California women with binge eating disorder.

For the study, the women were fitted with brain-stimulating implants like the ones used to treat epilepsy. Researchers recorded their brain activity for six months and saw the expected signals in the nucleus accumbens just before binge episodes.

By the end of the six months, both women had lost at least 11 pounds.

Over the following six months, the implants automatically stimulated the women’s nucleus accumbens regions whenever the craving-associated signals were detected. The women say this reduced the frequency of their binge episodes and their feelings of being out-of-control.

“It’s not like I don’t think about food at all,” Robyn Baldwin, one of the participants, told the New York Times. “But I’m no longer a craving person.”

By the end of the six months, both women had lost at least 11 pounds and one no longer qualified as having binge eating disorder. No serious adverse side effects were reported.

The cold water: A six-month study involving just two people isn’t enough to say that deep brain stimulation could be an effective treatment for binge eating disorder. It needs to be tested in at least 100 people before it can be approved by the FDA, according to the New York Times report.

Studies would also need longer follow up to show that the short-term weight loss and reduced cravings translated into lasting results.

The Penn team is already enrolling four participants for a larger study.

The researchers note in their study that the upfront cost of the deep brain stimulator is high, meaning the treatment could be financially out of reach for many people who might benefit if it ever is approved.

Still, there’s a significant need for more ways to overcome this eating disorder, and as deep brain stimulation becomes more common, the cost of the devices and implantation surgeries could become more affordable.

Looking ahead: The Penn team is already enrolling four participants for a larger study, and it plans to follow the original participants for up to three years — both were given the option of having their brain stimulators removed a year after implantation, and both declined.

“This was an early feasibility study in which we were primarily assessing safety, but certainly the robust clinical benefits these patients reported to us are really impressive and exciting,” said senior author Casey Halpern, who had contributed to the 2017 research while at Stanford.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].