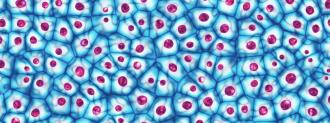

The human body is made up of trillions of tiny cells that control everything from what we look like to what kind of pizza toppings we enjoy. But, despite the huge impact these cells have on our lives, explaining precisely how they’re having this impact is an extremely tricky scientific question — and one with extreme scientific importance for identifying and preventing disease.

An international consortium of researchers hopes that their project, the Human BioMolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP), can begin to solve this problem by helping scientists better visualize this internal, cellular world.

The project’s first set of open-source data, which contains over 300 samples from seven types of organs, with details down to individual cells, was released to the public and scientific community in September and could be the beginning of a framework to help scientists create an interactive, 3D atlas of the human body.

Why We Need a Map

If a large scientific project exploring the human body sounds familiar, it’s because scientists accomplished a similar task in the early 2000s when they mapped the human genome. This genome project taught scientists the fundamental DNA make-up of human beings, but it still didn’t solve all questions about how our bodies work.

If genes are the instruction book your body uses to run, cells are the messengers who carry out those instructions. How these actions look and interact in real-life is the question this new project hopes to answer.

The goal of this project, which is a collaboration between 18 research institutions across the United States and Europe, is to use healthy tissue samples to build an interactive platform for scientists to explore different parts of the human body at the cellular level, like an anatomical version of Google Maps.

Similar to how Google Maps can help you navigate an unknown city or even identify hidden streets in your own neighborhood, HuBMAP is designed to help scientists explore different functions and connections between cells in the human body.

By using only “healthy” tissue to create this map (meaning, tissue free of pathologies), HuBMAP can be used as the ultimate cheat sheet to compare diseased tissue samples against. For example, visualizing the relationships between cells in healthy breast tissue can help scientists better understand the changes caused by breast cancer.

This crucial baseline comparison can then help scientists better develop treatments for diseases, Jonathan Silverstein, a member of the research consortium and visiting professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, explained in a statement.

“Comparing normal cells to different disease conditions will be very informative for developing strategies to treat a variety of diseases.”

The Data

The inaugural data released by the team this month contains tissue samples from 33 posthumous donors, from their heart, kidney, large intestine, small intestine, lymph nodes, spleen and thymus.

The samples were analyzed with microscopy, mass spectroscopy, and whole genome and RNA sequencing. Together, these techniques help scientists see the super small cells that make up these tissues and how they interact.

Using HuBMAP’s online portal, anyone can toggle between anonymized information on the donor, tissue samples, and full processed datasets and interactive visualizations.

While this information may be baffling the general public, the project team says that this kind of data could be used by surgeons to explain disease progression and interventions to patients, by computational biologists to better understand the progression of different diseases, and even by drug developers to find new treatment uses for drug candidates.

More to come

Tissue samples from just over 30 donors does not a full-fledged human atlas make, but the researchers say that this inaugural data release is only the beginning.

In addition to adding samples from more organs in the future the team also hopes to expand the diversity of its donor pool, as well, to encompass samples from a wider range of human bodies. All of the samples so far came from universities in the United States, and all current samples came from either white (26) or Black or African American donors.

As this project continues to expand its offerings, Silverstein says he believes it will be an important resource for a long time to come.

“I’ve done a lot of big projects in my career, but this is without a doubt the most exciting one, because the number of ways this is going to be used is just extraordinary,” said Silverstein. “It will be a large, national resource for a long time.”