Glioblastoma, a rare but aggressive brain tumor, is the deadliest form of cancer. Most patients live only about one year after diagnosis; just 6% will live for five years. Because the tumor is in the brain, therapies for it are very difficult to administer — and all glioblastomas eventually recur, although they can potentially be held in check with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

The standard procedure now is surgical removal of the tumor, followed by radiation or chemo. Unfortunately, these stalwarts of cancer treatment have big downsides; radiation can damage healthy tissue, and getting chemo to the brain is difficult, thanks to a powerful shield known as the blood-brain barrier.

Now, Northwestern University researchers have found a way to open that barrier, allowing more effective chemo drugs into the brain at higher concentrations. In a new clinical trial, they showed that a skull-implanted ultrasound can temporarily open the blood-brain barrier, creating a window for chemotherapy to permeate large swaths of the brain.

“This is potentially a huge advance for glioblastoma patients,” lead investigator Adam Sonabend, associate professor of neurological surgery at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, said.

Glioblastoma, a rare but aggressive brain tumor, is the deadliest form of cancer. And because the tumor is in the brain, walled away behind the blood-brain barrier, therapies for it are very difficult to administer.

The skull wall: Like bouncers manning the club doors, the central nervous system has a number of properties that it uses to keep the vibes right in the brain.

These are collectively called the blood-brain barrier, which strictly controls the movements of cells, ions, and molecules between circulating blood, which goes everywhere, and the central nervous system, which is an exclusive club. This ensures a stable environment for the brain, as well as protecting it from viruses, bacteria, toxins, and other nasty things.

While keeping your brain safe and sound is generally a good thing, the blood-brain barrier does present a formidable challenge when you want something to reach the brain — like, say, cancer medicine.

There are brute ways around the barrier, including administering medicine directly into the spine or going through the skull, a surgical end-around. Labs are trying to develop various ways to treat glioblastomas, including chemo pumps that administer drugs directly to the tumor, attacking supply lines to the cancer, and a special gel to fill the hole left by the tumor after surgery.

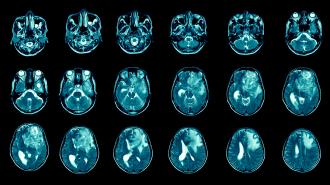

Researchers have used ultrasound to temporarily open the blood-brain barrier, allowing cancer drugs into the brain.

Opening the gate: The Northwestern team is taking a different approach: opening the barrier temporarily using ultrasound. And they’re already into clinical trials.

Published in The Lancet Oncology, this is also the first in-human trial using an implantable ultrasound to temporarily open the blood-brain barrier.

The study enrolled 17 patients with recurrent glioblastoma between October 2020 and February 2022. Patients underwent surgery for tumor resection and to have the ultrasound device implanted. The treatment, a four-minute procedure done while the patient is awake, began within a few weeks of implantation.

Patients were given an IV chemo drug, paclitaxel. Normally, this drug would struggle to cross the blood-brain barrier, and while paclitaxel has shown potential when directly injected into the brain, it has been associated with toxic effects including brain inflammation and meningitis, Sonabend said.

When low-intensity ultrasound pulsed from the devices was combined with intravenous microbubbles, the blood-brain barrier was opened for roughly an hour.

“There is a critical time window after sonification when the brain is permeable to drugs circulating in the bloodstream,” Sonabend said.

“This is potentially a huge advance for glioblastoma patients.”

Adam Sonabend

The results: The ultrasound led to a four-to-six fold increase in chemo concentration in the brain. The treatment was also found safe and well-tolerated (which was all this study was designed to measure); some patients received up to six cycles of sonification, given every few weeks.

These results have informed an ongoing phase 2 trial of patients with recurrent glioblastomas, which is designed to figure out if the technique actually prolongs the life of patients. These patients will receive a combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin, which has been proven in fighting various other cancers.

This technique may reach well beyond brain cancer; the ultrasound technique “opens the door to investigate novel drug-based treatments for millions of patients who suffer from various brain diseases,” Sonnabend said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].