This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 wasn’t the first to wreak havoc on humanity — six other coronaviruses have made the jump from animals to humans, and two of them (SARS and MERS) cause serious diseases.

It’s almost certain that we’ll encounter other dangerous coronaviruses in the future, so some researchers are trying to get ahead of the problem by developing vaccines that could protect against all coronaviruses, including ones that don’t even exist yet.

Vaccine evaders

When a virus infects you, certain parts of it — called “antigens” — will catch the attention of your immune system, triggering the body to create antibodies and T cells specifically designed to help recognize and neutralize that virus.

Vaccines introduce antigens in a way that doesn’t cause an infection, but that still triggers the immune system. If the real virus ever enters your body in the future, the immune system will quickly launch an attack to protect you from infection.

By the time boosters reach people, a different variant may already be on the rise.

While some vaccines, like the one for measles, offer lifelong protection, that’s not the case for our COVID-19 shots. That’s partly because, unlike the measles virus, this coronavirus regularly mutates into new variants as it spreads from person to person.

Mutations in the coronavirus’ spike protein — the antigen used for the COVID-19 vaccines — can prevent our immune system from effectively neutralizing the virus, causing an infection. Variants with those mutations can then spread more easily and outcompete the older variants.

Currently, the best way to address this is through regular booster shots updated to match the more recent variants, much like the seasonal flu shot. But the virus is mutating so rapidly that by the time the FDA decides which variant to target and vaccine manufacturers design, test, and manufacture the boosters, a different variant may already be on the rise.

Quite aside from the constant drift of COVID-19 through mutation, there’s an ever-present risk of a new pandemic from different coronaviruses, like SARS or MERS, that can spill over from animals to humans.

Universal coronavirus vaccines

Instead of continuing to play catch-up, researchers at Cambridge University want to develop a universal coronavirus vaccine, meaning one that would work not only against all variants of COVID-19 but against all coronaviruses.

“In nature, there are lots of these viruses just waiting for an accident to happen,” said lead researcher Jonathan Heeney. “We wanted to come up with a vaccine that wouldn’t only protect against SARS-CoV-2, but all its relatives.”

The vaccine they’ve created has already proven capable of inducing a strong immune response against a variety of coronaviruses — including all known variants of the COVID-19 virus — in mice, rabbits, and guinea pigs, and they are already testing it in people.

“This technology combines lessons learned from nature’s mistakes and aims to protect us from the future.”

Jonathan Heeney

Instead of using an existing antigen — like the coronavirus’ spike protein — for its vaccine, the Cambridge team designed its own antigen from scratch, called “T2_17,” using synthetic biology techniques.

To determine what this antigen should look like, they studied the spike proteins of many different coronaviruses, focusing on a part of the virus that’s essential for replication, known as the receptor binding domain (RBD).

Using computer simulations, they identified parts of the RBD that were unlikely to mutate in the future. Armed with that information, they designed an “optimized” antigen for their vaccine.

“It opens the door for vaccines against viruses that we don’t yet know about.”

Jonathan Heeney

During their preclinical studies, they demonstrated how this antigen could be used with three types of vaccines — a DNA vaccine, an mRNA vaccine, and a viral vector vaccine — to trigger a protective immune response against all known COVID-19 viruses, the SARS virus, and other major coronaviruses.

A needle-free DNA vaccine based around the T2_17 antigen has been in a phase 1 safety trial since December 2021, where it is being tested as a booster for people who’ve already been vaccinated against COVID-19. In April 2023, the trial expanded to include a second UK city.

“Unlike current vaccines that use wild-type viruses or parts of viruses that have caused trouble in the past, this technology combines lessons learned from nature’s mistakes and aims to protect us from the future,” said Heeney.

“These optimized synthetic antigens generate broad immune responses, targeted to the key sites of the virus that can’t change easily,” he continued. “It opens the door for vaccines against viruses that we don’t yet know about.”

Looking ahead

The Cambridge team isn’t the only group hoping we can replace yearly COVID-19 boosters with a universal coronavirus vaccine.

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute are developing a vaccine centered on a part of the spike protein called the S2 subunit, which they’ve determined is less likely to mutate than other parts of the protein.

Like the Cambridge group, researchers at UK startup baseimmune designed their own antigen for a universal coronavirus vaccine, combining bits of existing proteins and ones invented by their AI platform — that shot is currently in the preclinical stage of development.

“Universal vaccines … could provide [vital] protection against severe disease from the next pandemic.”

Karin Bok

While at the University of North Carolina, immunologist David Martinez, now an assistant professor at Yale University, led the development of an mRNA vaccine that teaches the body to make a custom-designed antigen based on the spike proteins of four coronaviruses. That shot is also in preclinical trials.

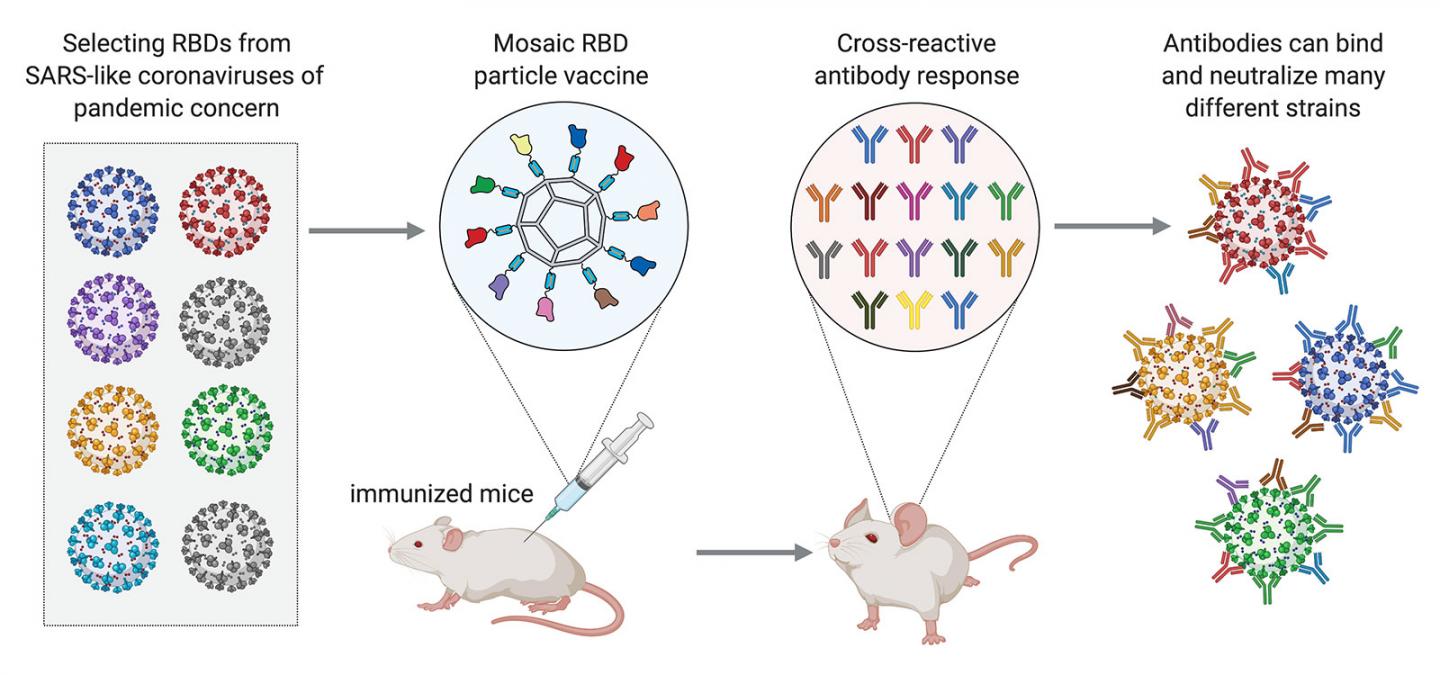

A team from CalTech, meanwhile, has packed RBDs from eight different coronaviruses into a single “mosaic” vaccine, and in mouse tests, it protected against those coronaviruses and four others. In 2022, they received $30 million from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) to prepare that vaccine for clinical trials.

Even if any of these vaccines perform well against past and present coronaviruses in trials, it’ll be impossible to know whether they can protect against future coronaviruses until those viruses actually start to emerge.

Hopefully, universal shots could prevent such viruses from ever taking hold at all, but even if they can’t, they might buy us time to develop more effective vaccines specifically tailored to those future coronaviruses.

“When we think about pandemic preparedness, what we’re most worried about is the first few months, before vaccines can be prepared,” said Karin Bok, a vaccine researcher at the National Institutes of Health. “Universal vaccines … could provide [vital] protection against severe disease from the next pandemic.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].