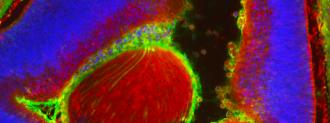

In 2020, University at Buffalo scientists announced that they’d found a way to grow millions of human cells in mouse embryos.

Now, they’ve published a how-to guide so that others can make their own mouse-human chimeras, a move that could lead to treatment breakthroughs for countless diseases — and maybe even growing human organs in animals.

The challenge: Lab mice play a huge role in medical research, giving scientists a way to study disease progression and test new treatments in living organisms without experimenting on people.

However, while mice and humans have similar DNA, they’re still very different animals, and much of what we see in mouse models doesn’t translate to people.

“These mice more accurately reflect the human condition.”

Jian Feng

Why it matters: UB’s mouse-human chimeras offer the best of both worlds, giving researchers a way to study the impact of diseases or treatments on human cells in vivo (that is, in a live animal), without putting any people in harm’s way.

“These mice contain critical human cells, tissues, or even organs so that they more accurately reflect the human condition,” senior author Jian Feng said in a press release. “With our method, the human cells are made along with the mouse during the development of the mouse embryo.”

DIY mouse-human chimeras: The newly published protocol guides researchers through the three-step process UB developed to create the chimeras.

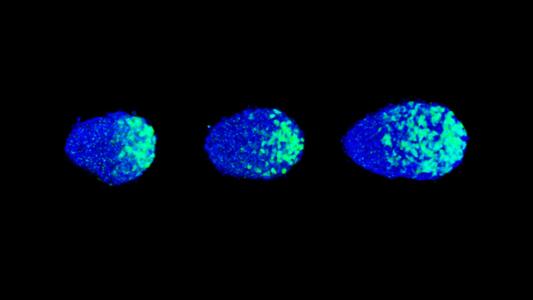

That starts with coaxing “primed” stem cells, derived from people, into their less-developed “naïve” state. Next comes getting those naïve stem cells to grow within a mouse embryo, and finally, the protocol explains how to quantify the number of human cells that develop in the mouse-human chimeras.

“It may fundamentally change our understanding of human biology and medicine.”

Jian Feng

Looking ahead: UB was encouraged to publish the guide following significant interest from the scientific community.

Now that the protocol is out there, Feng is confident that researchers will run with it, using the mouse-human chimeras to study diseases, develop potentially life-saving treatments, and maybe even figure out how to grow transplantable human organs in animals.

“It will stimulate unforeseen discoveries and applications that may fundamentally change our understanding of human biology and medicine,” he said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].