A new study found that spending enough time in space has a major impact on astronauts’ brains — but thankfully, it appears reversible with enough time back on Earth.

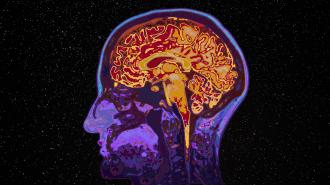

The challenge: Inside your brain are four hollow spaces, or “ventricles,” where specialized cells produce cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a liquid that nourishes the brain, removes waste, and protects tissue against physical injury.

Normally, CSF flows through the ventricles, around the brain, and down the spinal cord. But research has shown that spending time in space, where the pull of gravity on the body is weakened, appears to affect this flow, leading to overfilled, enlarged ventricles.

What’s new? In an attempt to further understand this phenomenon, researchers at the University of Florida studied MRIs of 30 astronauts’ brains before and after they visited space on trips lasting 2 weeks, 6 months, or 1 year.

Based on this analysis, spending 2 weeks in space doesn’t produce any measurable change in brain ventricle volume. Scans of 18 astronauts who spent 6 months in space, however, showed significant increases in ventricle size.

“It takes about three years between flights for the ventricles to fully recover.”

Rachael Seidler

When the researchers looked at the scans of 4 astronauts who spent a year in space, though, their ventricles weren’t much larger than those in the 6-month club.

“This pattern suggests that the majority of ventricular changes in flight occur during one’s first six months in space,” the researchers wrote in their NASA-funded study, published in Scientific Reports.

Once astronauts were back on Earth, their ventricles began slowly shrinking back down to size — for those who spent 6 months in space, an average of 55-64% of the extra volume was gone by the time they’d been home for 6-7 months.

“Our study shows it takes about three years between flights for the ventricles to fully recover,” said study co-author Rachael Seidler.

Why it matters: NASA’s future Mars plans will require astronauts to spend at least 2 to 3 years in space, so the discovery that ventricle enlargement appears to taper off after 6 months is reassuring — if the cavities just kept getting bigger, NASA would have to rethink the crewed missions.

The fact that stays of less than 2 weeks don’t seem to have much of an impact, meanwhile, is a boon for space tourism companies — it might be difficult to convince people to vacation in space if it meant their brain was going to undergo significant structural changes.

“Allowing the brain time to recover seems like a good idea.”

Rachael Seidler

Looking ahead: More research is needed to find out how these changes in astronauts’ brains might affect their health, but in the meantime, Seidler believes astronauts and space agencies would be wise to err on the side of caution.

“We don’t yet know for sure what the long-term consequences of this is on the health and behavioral health of space travelers, so allowing the brain time to recover seems like a good idea,” she said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].