First released in 1979, the Sony Walkman is now an icon of the 1980s, eliciting nostalgia for the “good old days” of owning music rather than renting it. Affection for the device is now universal, but that wasn’t always the case…

The sudden rise of headphone-wearing pedestrians — spurred by Sony’s lightweight headsets, which were 17% the weight of others’ devices — caused unease about an unfamiliar new world quickly coming into view.

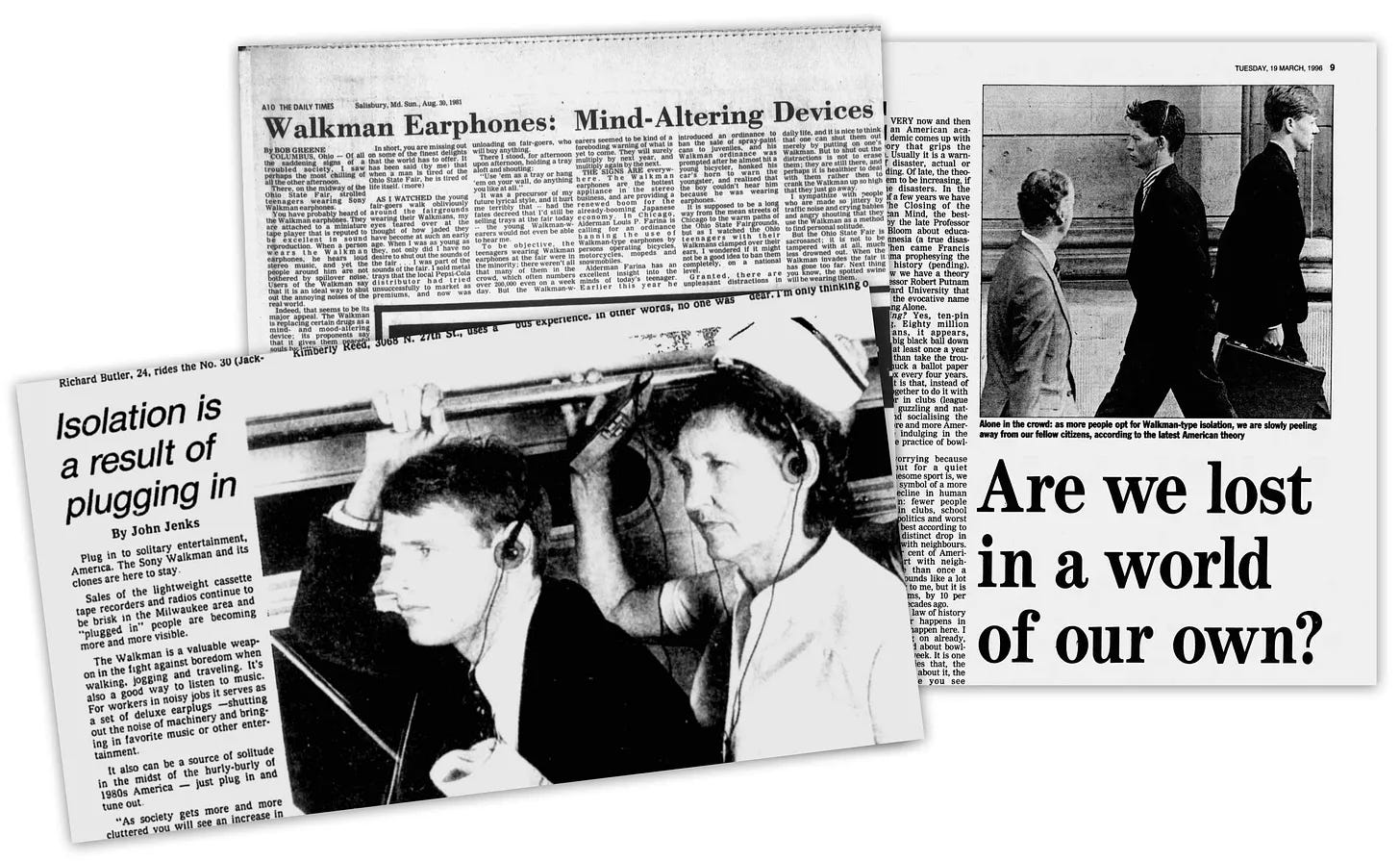

Some said it was a sign of a continued rise of Reagan- and Thatcher-style individualism. Cultural critic Allan Bloom deemed the Walkman “a nonstop…masturbational fantasy” in his 1987 book “The Closing of the American Mind.” Neo-Luddite John Zerzan saw the Walkman as part of a modern trend that encouraged a “protective sort of withdrawal from social connections.” Thomas Lipscomb, chief of the Center for the Digital Future, equated it with the euphoric drug “soma,” from Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” creating, as he put it, “an airtight bubble of sound” that was nothing but a “sensory depressant.”

In other words, it all felt “a bit Black Mirror,” as one might say today. (Credit to this 1999 Reason Magazine article for this collection of quotes)

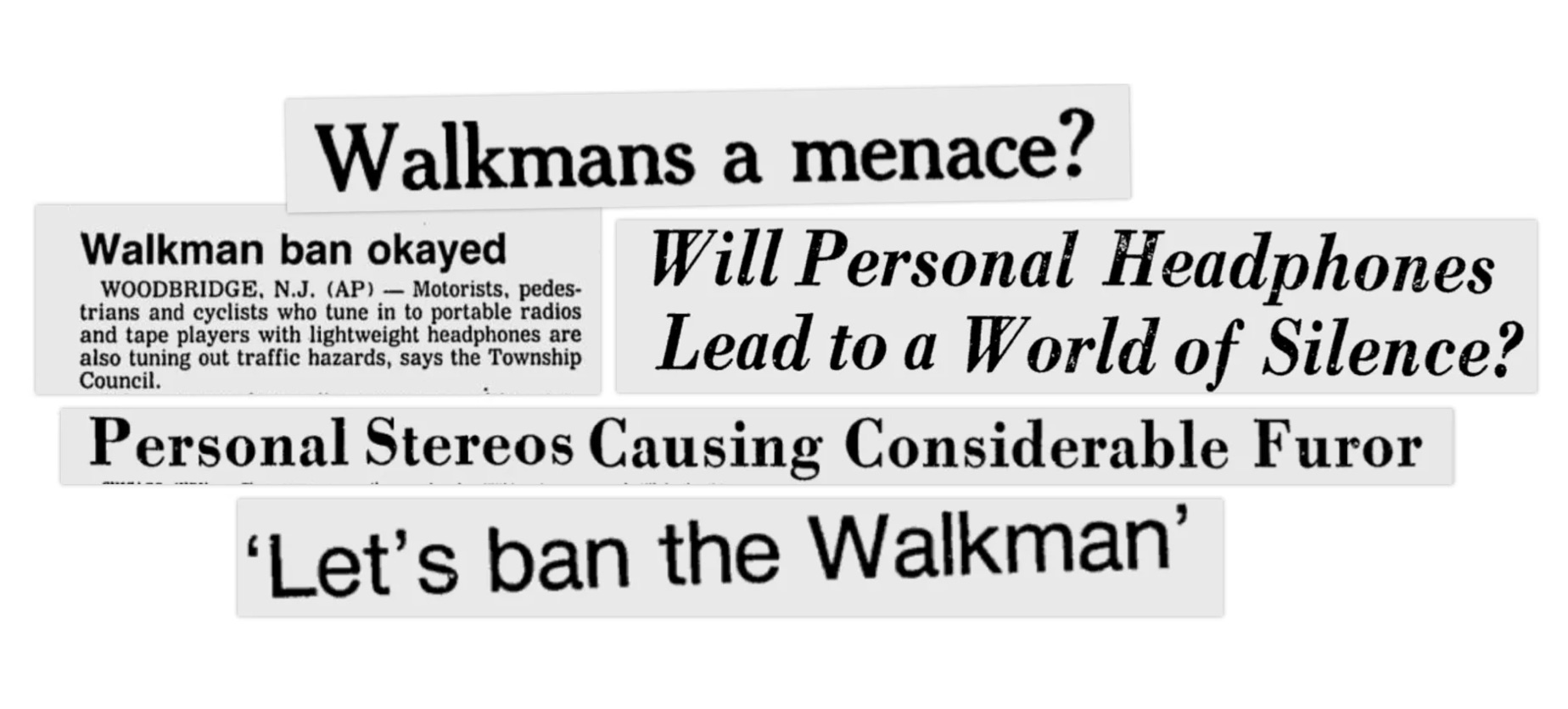

The Walkman, critics claimed, was more than just music to one’s ears. It was a tool of societal disconnect and, for government officials and law enforcement, a danger on the roads because it limited the hearing of drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians.

After a number of accidents involving Walkman headphones, numerous states across the US swiftly put into effect (or proposed) restrictions, many related to headphone use while driving or cycling. Among them were statutes in California, Florida, Georgia, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington.

The New Jersey township of Woodbridge went a step further, forbidding not just driving or biking, but even crossing the street while wearing Walkman headphones.

The price for breaking this prohibition? A potential two-week stay in jail and a fine. The law made national and international news, including the BBC who got reactions on the street.

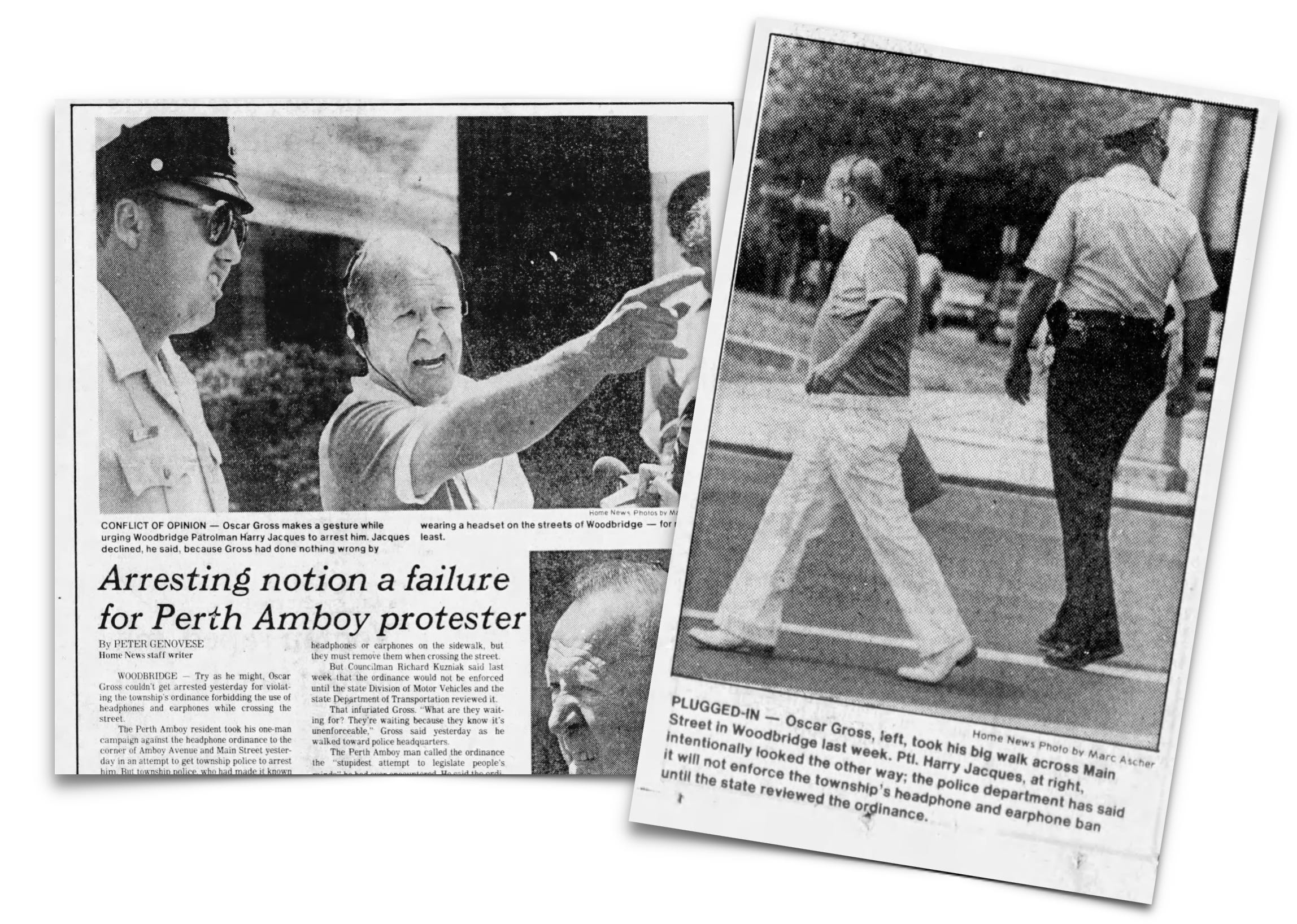

The day the law was put into effect, Oscar Gross, a retiree from a neighboring town, was spurred into action. Seething, he approached Police Sergeant Lou Monzo, purposefully donned his headphones, and crossed the street.

The outcome of this small act of civil disobedience? Gross became the first person to receive a citation for wearing headphones (even though they weren’t plugged into anything). Undeterred, he stated in an interview, “I’m prepared to go to jail for 15 days just to prove a point.”

Gross ended up being interviewed for national outlets, as did members of the Woodbridge town council. However, to his disappointment, Gross was not sent to jail. After the judge imposed a $50 fine, which was later suspended, a frustrated Gross said to a journalist, “He didn’t even give me the opportunity to say that I was willing to serve time in jail.”

“No municipality has the right to tell somebody what they can wear.”

Oscar Gross

Oscar Gross was preparing to take the case all the way to the Supreme Court, but backed out after someone was killed crossing the street while wearing headphones — the kind of tragic anecdote that is the inevitable and unavoidable price of freedom.

This chapter in techno-pessimism is a good reminder that nostalgia tends to elicit amnesia about the resistance new technologies once faced. After all, who would have thought the “good old days” could ever have been considered a bad, brave new world?

This article was originally published on Pessimists Archive. It is reprinted with permission of the author.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].