The following is Chapter 10 from the book The Techno-Humanist Manifesto by Jason Crawford, Founder of the Roots of Progress Institute. The entirety of the book will be published on Freethink, one section at a time. For more from Jason, subscribe to his Substack.

We are creatures not only of flesh and blood, but of mind and spirit. We need more than a full belly, a shirt on one’s back, a roof over one’s head. We need meaning and purpose. We need a goal to strive for, a grand project to contribute to. We need a heroic archetype to look up to and to emulate. In short, we need to know what to do and who to be.

Conventional morality takes us only so far. It may counsel us on prudence and temperance, and help us to avoid temptation and self-destructive behaviors. It may advise us on charity, and help us save lives and relieve suffering. It may encourage us to tolerance, and help us refrain from cruelty or bigotry. These may make us better people, but they are not enough to feed a soul. They do not inspire or invigorate. We seek more.

We have energy. It must be directed. We have indomitable will. It needs a goal. We have fighting spirit. It needs an object. We have aspiration to greatness. It needs a form.

In the past, we glamorized the warrior, fighting bravely for king and country. Today we know that war is not glamorous, it is hell. The fighter is no longer admired, and a more peaceful world has less need of him, anyway. War has not been eliminated, and we still need fighters, but this is not, nor should it be, the main archetype for aspiring heroes today.

Once, we had the frontier. Exploring the unknown, expanding into new territory, taming the wilderness—these were challenges worthy of our best efforts. But the frontier on land was closed more than a century ago, and the frontier of space, after Apollo was canceled, seemed to have closed almost as soon as it had opened. As the meme goes: born too late to explore the Earth, born too early to explore the stars… What are we just in time for? What is the new frontier?

The question is pressing. “The human society of the future desperately needs a frontier,” writes J. Storrs Hall: psychologically and ethically, we need a venue where “a majority of one’s efforts are not in competition with others but directly against nature,” otherwise we devolve into squabbling and status games.1 Similarly, Ross Douthat remarked that the closing of the frontier was a factor in “our era’s anxieties, in the sense of drift and stagnation and uncertainty,” and that the canceling of the Apollo program “coincided with a turning inward in the developed world, a crisis of confidence and an ebb of optimism and a loss of faith in institutions.” Douthat was writing about American “decadence,” by which he means not hedonism or luxury, but, quoting historian Jacques Barzun: “a very active time, full of deep concerns, but peculiarly restless, for it sees no clear lines of advance.”2

This restlessness seems to be felt in Silicon Valley. “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads,” lamented an early Facebook employee in 2011.3 “Silicon Valley has lost its way,” says the CEO of Palantir in a recent book: “the current generation of spectacularly talented engineering minds has become unmoored from any sense of national purpose or grander and more meaningful project.”4

Acutely feeling this lack, some propose a “retvrn” to a “traditional” past, to some allegedly lost wisdom of Christianity or of feudal peasants or of ancient Rome. This is a mistake. There are reasons we moved on from the past, and we don’t want to return to a world of constant warfare, or of racial bigotry, or one that deprives women of respect and autonomy. Like Chesterton’s wise reformer who would not tear down a fence until he understood the reason it had been erected in the first place, we should also not be hasty to replace fences without being clear on why they were removed.5 And if we are committed to progress, then we must be seeking to move forwards, not backwards—into an improved future, not a romanticized past.

In Chapter 4 I affirmed the human need for meaning and purpose, and argued that material progress empowers us to seek these non-material ends, but I left it to each individual to define that meaning for themselves. Now I will argue something more: that the idea of progress itself can provide meaning, that it can give us the grand project and the heroic archetypes that we need.

Progress is a grand project for humanity. It is a project with an illustrious past, one that stretches back millions of years—before the pyramids, before agriculture, before our own species; it is the legacy of the first hominin to improve the earliest stone tools. Improving upon tradition is our oldest tradition. And it is a project with a glorious future, one that extends as far in time and space as we can imagine, to the farthest reachable galaxies, on through the eons until we use up the last joule of free energy in the universe.

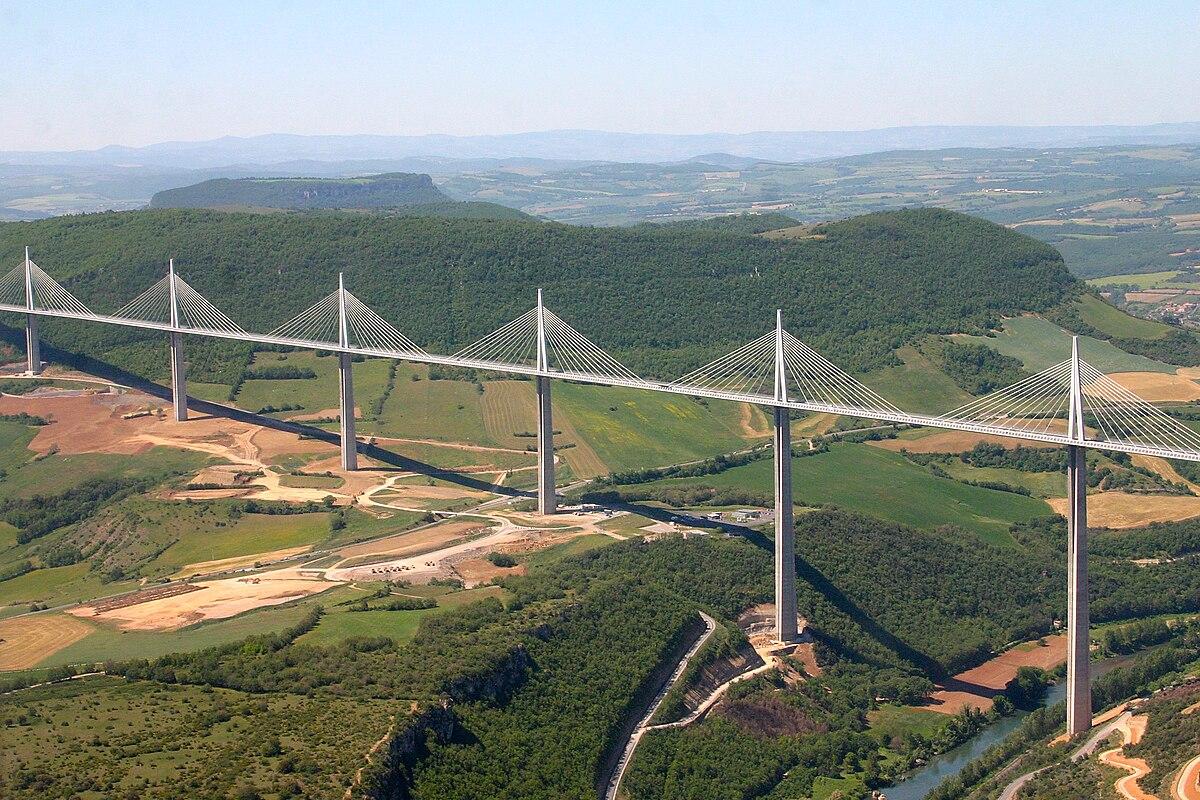

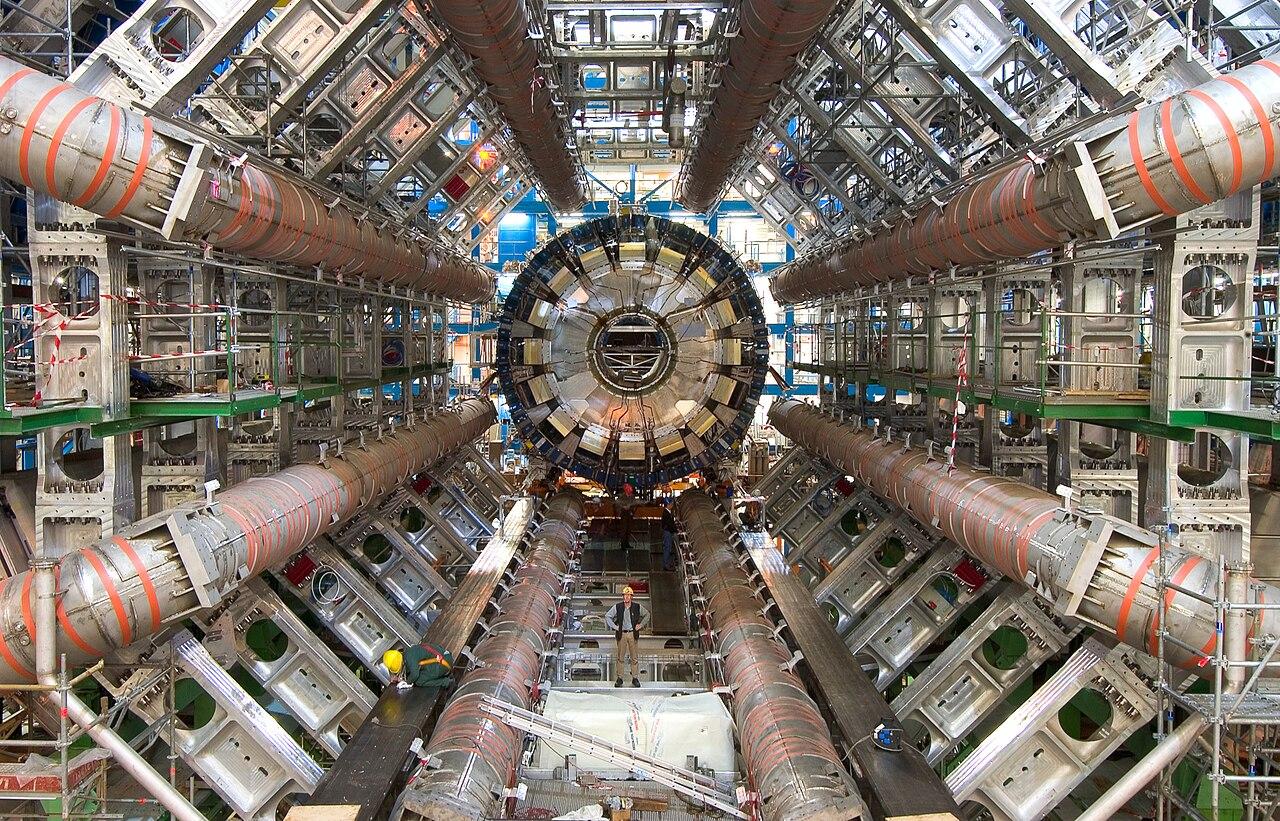

It is a project that produces marvelous artifacts, to inspire awe and wonder: from the Golden Gate Bridge to the Hoover Dam to the Millau Viaduct, from the sight of Starship lifting off into space to the majesty of a container ship heading into port, from the elegance of a jet turbine blade made from a single crystal of metal to the symmetrical geometry of the Large Hadron Collider. And it produces intellectual artifacts, too, that can inspire aesthetic sentiment: both Boltzmann and Dirac have physics equations on their memorial stones.6

It is a project for all of humanity. It does not seek to establish the supremacy of one nation or race, nor is it the exclusive property of one people. It is a project that all can contribute to and all benefit from. It is a cooperation much more than it is a competition, a project that gets better the bigger the team—thanks to the special nature of ideas, which can be shared infinitely without diminishment. Indeed, because of the expanding frontier of ideas, and the diminishing returns as we pluck the low-hanging fruit, it is a project that demands an ever-expanding team.7

It is a project that is justified, not by a faith or tradition that is meaningful only to one people, but by human nature, which requires an appeal only to reason and common sense. It is based on the needs of human life and well-being. And unlike conquest, it is purely constructive—as was said about James Watt’s achievements, it sheds no blood and makes no widows nor orphans.8

Unlike projects with humble aims such as the mere alleviation of suffering, it has an ambitious aim: to build an amazing world, to create marvels and wonders, to make magic and fantasy come true. To realize every dream of our ancestors: the never-empty cornucopia of food, light conjured from the darkness, immunity from disease, flight, creating life, exploring the stars, immortality. It is reaching for the full exercise of human capabilities and the full realization of our potential. The alleviation of suffering may speak to our compassion or pity, but to build an amazing future speaks to our sense of wonder, excitement, adventure, and romance.

If this then is humanity’s grand quest, who does it call for? The heroes of progress are the scientist, the inventor, and the founder.

These three play different roles: the scientist discovers new knowledge, the inventor creates new technology, the founder establishes a new business. But they have this in common: their challenge is to tackle Knightian uncertainty. They face a field of unknown unknowns, and no one can calculate the probability or predict the timing of their success. They stand alone against critics who say they’re idiotic or deluded, and they manifest unshakeable confidence that they will succeed, despite having no map of the path to their destination.

These roles deserve to be lionized. They should be glamorized as heroic archetypes. Children should look up to them and pretend to be them. Young adults should read their biographies and hang posters of them on the wall. Not because every individual scientist, inventor or founder is a hero—many are not—but because of the heroic potential in their work.

For one, it is the work that moves humanity forward. The scientist who discovers a material or a virus, the engineer who turns that into an engine or a cure, the founder who makes that available to the world, affordably, through a new business—those feats improve lives more than any charity.

But also, the work of science, engineering and business demands virtue. Ayn Rand wrote that all productive work “is the road of man’s unlimited achievement and calls upon the highest attributes of his character.”9 To push forward the frontiers of science, technology and industry, in particular, requires a certain energy, an ambition to not just coast doing comfortable work, but to do something new and important, even though that will be far more difficult. It requires the vision to see what to strive for, when no one else can. It requires independence of mind, to find your own vision instead of following the herd. It requires the courage to devote yourself to such an effort, with no guarantee that you will succeed and with no one believing in you but yourself. It requires the strict rationality and ruthless honesty to admit to yourself what is working and what is not, and which of your cherished ideas you must discard. It requires focus and dedication over many years of effort. It requires persistence and resilience in the face of setbacks. “All material production,” Rand concluded, “is an achievement of the spirit.”10

You in these fields should see your work imbued with moral meaning. You are engaged in a noble quest, continuing the grand project to better the human condition—no matter whether you are curing cancer or building virtual reality games—and your calling has never gotten its due.

Your work is lonely, difficult and uncertain—and you will get little support from society. Until you succeed, they will ignore and ridicule you. Once you succeed, they will fight and denounce you. And when you win, someone will try to steal the credit.

You will need to seek courage in difficult times. Seek it in the struggles and eventual triumphs of the great creators, from Archimedes to Pasteur to Steve Jobs. Seek it in the epic of human progress. Seek it in the moral meaning of your work.

All of this is not to praise your choices, but to inspire your efforts. This quest demands the best you have to offer: the best of your intellect, your conscience, and your spirit. You must remember your responsibility: to see that technology is used for good, to ensure that it is developed and deployed safely, to refuse to deliver it into the wrong hands. But if you show that courage and that integrity—then you may one day take your place among our greatest heroes.

1: Hall, Where is my Flying Car?, 303.

2: Douthat, Decadent Society, 5.

3: Ashlee Vance, “This Tech Bubble is Different.”

4: Karp, The Technological Republic, 20, 29.

5: Chesterton, The Thing, 29.

6: “Paul Dirac”; “Boltzmann’s Grave.”

7: See discussion in Chapters 3 and 7.

8: The Chemist, 251. See Chapter 9.

9: Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 18.

10: Rand, Journals of Ayn Rand, 616.