The following is Chapter 9, Section 2, from the book The Techno-Humanist Manifesto by Jason Crawford, Founder of the Roots of Progress Institute. The entirety of the book will be published on Freethink, one section at a time. For more from Jason, subscribe to his Substack.

In part 1 of this chapter, we saw the deep belief in progress that existed in the late 19th century and in some forms through the mid-20th. What happened to that spirit?

The first thing we should realize is that this belief in progress was historically unique. In most places and times before the modern West, the concept of progress did not exist.1

Many ancient cultures viewed history as a cyclical pattern of ups and downs, or even as a story of decline: the past as a golden age, from which we have fallen. Europeans in the Middle Ages, looking upon the ruins of coliseums, aqueducts, and pyramids, understandably thought that their ancient ancestors must have been the greatest people ever to have lived. As they rediscovered ancient texts, some thought that those ancestors must have possessed all knowledge of consequence as well. They—the “moderns”—thought themselves unable to surpass those achievements or that learning. Economic historian Joel Mokyr, taking a phrase from historian Carl Becker, calls this “ancestor worship,” and it is the antithesis of the idea of progress.2

Ancestor worship in Europe, Mokyr says, began to weaken around the end of the 1400s, with the voyages of discovery. An entire continent was discovered that had never been mentioned in the classic texts: apparently the ancients had not possessed all knowledge of consequence. Those ancestors also didn’t know about the compass, gunpowder, or the printing press.3

Francis Bacon, for one, took inspiration from this: in Novum Organum, he wrote that “noble inventions may be lying at our very feet”—that is, if these possibilities lay undiscovered for so long, what else might be out there, just waiting to be found?4 From these early examples, Bacon and his contemporaries extrapolated out a vision of a scientific and industrial revolution—a vision that eventually came true, although its realization took centuries. He counseled courage, saying that “by far the greatest obstacle to the progress of science” is “that men despair and think things impossible.”5

If by the late 1600s there was any doubt about the ancients vs. the moderns, Isaac Newton laid it to rest. His theory of universal gravitation and explanation of the solar system were so clearly superior to anything that had been offered before that there was no question left: the moderns had surpassed the ancients. The pattern of history was neither endless cycles nor a long decline: it was an upward trend. Progress was possible.6

In the era that followed, an unbridled optimism was expressed by leading intellectuals, such as the French Enlightenment thinker Nicolas de Condorcet. In 1794, he wrote a Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind, in which he forecast virtually unlimited progress in every dimension—not only in science and technology, but in morality and society. He spoke of the equality of the sexes, and peace among nations. And he believed that all forms of progress went together, saying that prosperity naturally disposes people to “humanity, benevolence, and justice,” and that “nature has connected, by a chain which cannot be broken, truth, happiness, and virtue.”7

Amazingly, he wrote these words while hiding out from the French revolutionary government, which was hunting him down to execute him because he had dared to criticize the Constitution of 1793. Unfortunately, he could not hide out forever: he was captured, and soon died in jail.8 Evidently the moral perfection of mankind was slow in coming.

But technological progress was racing ahead. After the railroad, the telephone, and the light bulb, progress was no longer a possibility for philosophers to theorize about, but a reality being brought daily into the homes and lives of ordinary people. The flowering of the industrial age, and the fruit it bore for the average person, engendered the popular belief in progress that we have just seen. At the end of the 19th century, it seemed as if the optimism of the Enlightenment had been justified after all.

But, flush with the grand success of reason and science to improve human life, society stumbled into some critical errors. These errors would create a crisis of optimism, one that posed a mortal challenge to the idea of progress.

One of those errors arose out of an excess of enthusiasm for “scientific management,” the imposition of order and system by technical managers. This approach had achieved great success in the Ford assembly line and production system, and was championed by Frederick Taylor in his popular 1911 book Principles of Scientific Management. But Taylor and others decided that scientific management should be applied to everything—not just to factories, but to all of society. Taylor wrote that its principles “can be applied with equal force to all social activities” including the management of “our churches, our philanthropic institutions, our universities, and our government departments.” The Progressive party that Teddy Roosevelt ran under in 1912, writes historian Thomas Hughes, “was not content that experts bring order, control, system, and efficiency only to resources and work; they wanted social scientists—also ‘scientific experts—to direct their reforming zeal to city, state, and federal government.’” Even the conservationist movement of the time “advocated that decisions about conservation be made scientifically by experts. … This approach expressed a technological spirit spread by engineers, professional managers, and appliers of science, a belief that there was one best way.”9

This belief in the “one best way,” imposed top-down by “scientific management,” was called “high modernism” by James C. Scott.10 I will call it “technocracy”: rule by a technical elite.

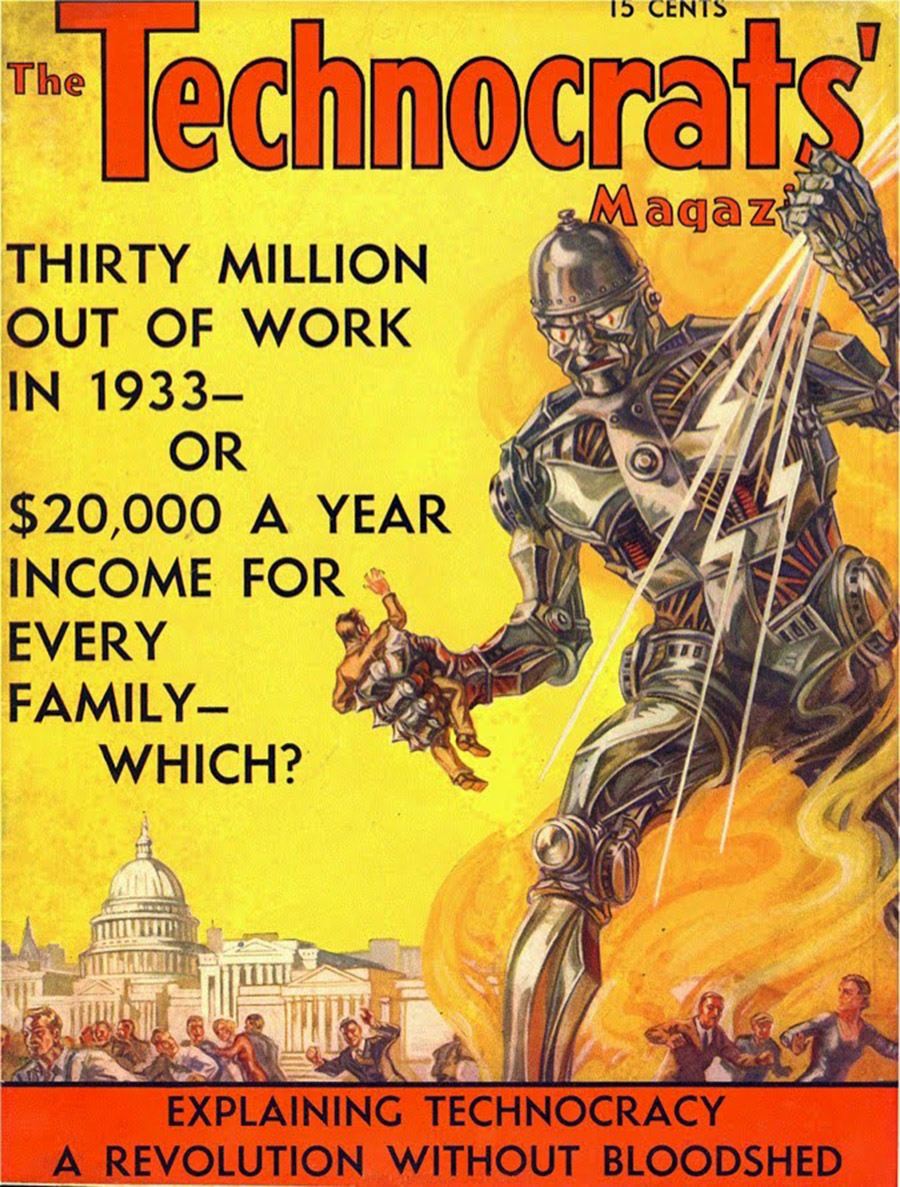

The economist Thorstein Veblen took technocracy to the extreme: “the entire industrial system of the country,” he said, should be controlled by “industrial experts, skilled technologists, who may be called ‘production engineers.’” Veblen was widely read, he was covered in Vanity Fair, and for a short time around 1920 he became “required reading among intellectuals.”11 H. L. Mencken wrote, in a mocking essay, that there had been “Veblenists, Veblen clubs, Veblen remedies for all the sorrows of the world.”12 In the 1930s, writes Charles Mann, there was “a crusading effort to establish a government of all-knowing, hyper-logical engineers and scientists,” inspired in part by Veblen. “Rather than allowing economies to dance to the senseless, febrile beat of supply and demand, Technocrats wanted to organize them on the basis of a quantity controlled by the eternal laws of physics: energy. … The leader of the system, the Great Engineer, would oversee a new nation, the North American Technate, a merger of North America, Central America, Greenland, and the northern bits of South America.” The organization pushing this program was called Technocracy, Inc.13

The new technology of electrical power was seen by politicians and social theorists as a chance to remake industrial society—and to do it right this time. They looked at the industrial areas of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Ohio and “blamed the growth of these congested, grim, and grimy regions on the lack of vision and effective leadership among social reformers during the first Industrial Revolution.” They “believed in the beneficial potential of modern technology,” but only “if it were kept under the control of planning and reforming social scientists supported by enlightened civic leaders rather than under the aegis of profit-motivated capitalists and industrialists.”14 Their visions were enacted in the 1930s under FDR and the New Deal, most notably in the Tennessee Valley Authority program to provide hydroelectric power from the Tennessee River.15

In the Soviet Union, the notion of centralized, top-down control reached a fuller expression in totalitarian communism. The Soviets were great fans of Fordism and Taylorism, and studied their works. The Communist Party translated and published Taylor’s book on scientific management; Ford’s autobiography went through at least four printings in the Soviet Union, and “was read with a zeal usually reserved for the study of Lenin.”16 In the 1920s, Stalin even named “American efficiency” as a characteristic feature of Leninism, praising it as an “indomitable force … without which serious constructive work is inconceivable.”17 The Soviets, naturally, sought to extract this industrial muscle from the individualism and capitalism of America and place it on a socialist foundation—which would not only, they believed, better benefit workers, but would be more efficient as well. (Of course, they were wrong: Communism never even came close to overtaking capitalism; indeed, millions died in famines, and the USSR eventually collapsed.)

A second grave mistake of the late 19th and very early 20th century was assuming that social progress would go hand-in-hand with material progress; that these would move almost in lockstep.

Condorcet had demonstrated an extreme commitment to optimism when he asserted, during the Reign of Terror, an unbreakable connection between truth and virtue. It was more plausible, however, to believe this in 1910. There had been four decades of relative peace since the end of the American Civil War in 1865 and the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.18 Slavery had been ended in the West; democratic republics and representative government were gradually replacing monarchy.19

Further, the expansion of trade was increasing peaceful ties between nations, and new inventions such as the telegraph were connecting far-flung peoples. The growth of communication networks in particular was seen as a powerful force for international unity, understanding, and brotherhood. One contemporary observer wrote that the telegraph “joins the sundered hemispheres. It unites distant nations, making them feel that they are members of one great family.” An ocean cable is “a living, fleshy bond between severed portions of the human family, along which pulses of love and tenderness will run backward and forward forever.” Another said that the electric spark of the telegraph “is the true Promethean fire which is to kindle human hearts. Men then will learn that they are brethren, and that it is not less their interest than their duty to cultivate goodwill and peace throughout the earth.’’20

Progress, up through this era, was conceived of as a unity: material and social progress were advancing together, driven by fundamental causes. And if the scientific and technological progress prophesied by Bacon had finally arrived, perhaps the moral and social progress prophesied by Condorcet would soon come as well.

Some thinkers saw progress as not just possible but inevitable, the product of cosmic forces or divine will.21 Herbert Spencer saw moral progress as a form of natural evolution, writing in 1851 that “the ultimate development of the ideal man is logically certain … Progress, therefore, is not an accident, but a necessity … surely must the things we call evil and immorality disappear.”22 H. G. Wells also saw progress as driven by impersonal forces, and said in 1902 that (absent some asteroid impact or fatal pandemic): “Everything seems pointing to the belief that we are entering upon a progress that will go on, with an ever-widening and ever more confident stride, forever.”23

In particular, many at the time foresaw the end of war. A traditional, pessimistic view, in contrast, had held that war was inevitable, because all nations were driven to territorial expansion and profited by conquest. Norman Angell, in his 1910 book The Great Illusion, argued that this was no longer true in an industrialized society: when wealth is based on credit or contract, it can either be left to its owners or be destroyed, but it cannot be seized; and even enforcing morals or social institutions on a conquered people was impossible in the world of the printing press. Angell didn’t claim that the end of war was at hand, but by arguing that “[t]he warlike nations do not inherit the earth,” he showed how lasting peace was possible.24

Others who were even more optimistic dared to hope that world peace could in fact be achieved soon. Stanford president David Starr Jordan was reported to have said: “Future war is impossible because the nations cannot afford it.”25 Alfred Nobel, in 1893, wrote: “It could and should soon come to pass that all states pledge themselves collectively to attack an aggressor. That would make war impossible.”26 Andrew Carnegie, dedicating a new Peace Palace at the Hague in 1913, said that the end of war was “as certain to come, and come soon, as day follows night,”27 and as late as January 1914, he was “strong in the faith that International Peace is soon to prevail.”28

They were wrong.

The World Wars of the 20th century violently shattered those naive illusions. Technology and economic growth had not led to an end to war: they had made war all the more horrible and deadly. They had given us the machine gun, chemical weapons, and the atomic bomb—the most destructive weapon the world had ever seen, a product of modern science, technology, and industrial capacity.

Technology also wrought “creative destruction” in the economy, rendering entire professions obsolete, from blacksmiths to lamplighters. As early as the 1600s and continuing into the 1800s, angry groups of workers such as the Luddites smashed and burned machinery in protest.29 Further, technology and industry seemed to be concentrating wealth and power into a new elite: Rockefeller, Morgan, Carnegie. A country that just a few generations ago had fought a war to throw off monarchical rule was suspicious of what looked to many like a new aristocracy—especially as many city-dwellers were still living in cramped tenements, without even toilets or clean water. When the Great Depression hit, many decided that the management of the economy could no longer be trusted to these capitalists. Indeed, in the 1930s, there was a widespread belief that if the economy were run efficiently, the work week could be reduced to around 15 hours; economist Stuart Chase (who coined the term “New Deal”) claimed that the only thing preventing this was the “waste” produced by capitalism.30

Technology and industry also created new risks to health and safety. Large factories and plants, with heavy, powered machinery and high-temperature furnaces, led to an increasing scale of accidents; workers and their families were the ones who suffered.31 Other factories used chemicals that caused long-term health problems, such as necrosis of the jaw from the phosphorus used in matches.32 There were no standards for the handling of food and drink: meat packing plants were filthy, and milk was transported warm in open containers, literal breeding grounds for disease.33 There were no testing or safety standards for drugs, either, or even enforcement of truth in labeling, and patients suffered or died for it.34 Scientific discoveries sometimes held hidden dangers: x-rays were initially thought harmless, and were used at parties and carnivals as amusements; later they were found to cause radiation burns and sickness and even cancer.35

The change in sentiment after WW1 is stark. In a 1923 essay “Daedalus: or, Science and the Future,” biologist J. B. S. Haldane asked: “Has mankind released from the womb of matter a Demogorgon which is already beginning to turn against him, and may at any moment hurl him into the bottomless void?”36 And by 1935, historian Carl Becker was able to assert that “the fact of progress is disputed and the doctrine discredited,” and ask: “What, if anything, may be said on behalf of the human race? May we still, in whatever different fashion, believe in the progress of mankind?”37

Much of the rest of the 20th century can be understood as a response to this crisis. To be precise, two waves of responses.

The first response, in the mid-20th century, was to lean harder into technocracy. People still believed in progress—but felt it could no longer be trusted to the chaos of democracy and free markets. It had to be managed by a central authority.

In the 1920s, influential journalist and commentator Walter Lippmann wrote a number of books arguing that democracy was a “false ideal,” at least if it required an “omnicompetent, sovereign citizen” who was informed on and could judge all issues. “The individual man does not have opinions on all public affairs. He does not know how to direct public affairs. He does not know what is happening, why it is happening, what ought to happen.”38 And public opinion is too easily manipulated by the press and by political leaders, a process he called the “manufacture of consent.”39 Thus: “We must abandon the notion that the people govern … people support or oppose the individuals who actually govern.”40 “Executive action is not for the public,” he posited, nor are the merits of specific questions; the public’s only role is to align itself behind one leader or another.41 Lippmann was part of a school of “democratic realists,” who believed, according to one contemporary scholar, that democracy “must be redefined as rule for the people but not by the people. Rule would be by informed and responsible ‘men of action.’”42

In the US, progress in the mid-20th century often took the form of large federal projects: the work programs of the New Deal, the industrial mobilization for WW2, the interstate highway system, the Apollo program. The success of military research during WW2 led to a massive ramp-up in federal funding for science starting in the 1950s; today large central funders like the NIH dominate funding for basic research.43 Builders like Robert Moses in New York were popular because they could figuratively and literally bulldoze through opposition. And when the public wept for joy at the polio vaccine in 1955, it was an expression not only of a belief in science and technology, but of trust in public health authorities and the scientific establishment.

The technocracy also tried to guard against the hazards of progress through new regulatory agencies and commissions that would exercise top-down oversight, from the FDA (1906) to the SEC (1934) to the FAA (1958).44 The Federal Register, an official publication of rules and regulations, ran 2,620 pages when it was first published in 1936, and had grown to over ten times that size by 1972.45

All of this made sense to the generation immediately after the wars, who still believed in progress. Many of the leaders of that era, including FDR, Truman, and Eisenhower, were born in the 19th century and came of age in the pre-war culture of optimism. But the generation that came next was raised in an atmosphere of fear and soul-searching, in a culture that was questioning the very idea of progress—and they decided to learn a very different lesson.

Progress had always had its critics. As early as 1750, Rousseau had declared that “the progress of the sciences and the arts has added nothing to our true happiness,” adding that “our souls have become corrupted to the extent that our sciences and our arts have advanced towards perfection” and that “luxury, dissolution, and slavery have in every age been the punishment for the arrogant efforts we have made in order to emerge from the happy ignorance where Eternal Wisdom had placed us.”46

Rousseau was only one of the earliest in a long line of such critics, stretching across centuries. Thomas Carlyle, in the mid-1800s, said that while the English had become wealthier, they were not happier, wiser, or better.47 He lamented the philosophic materialism of his age, the decline of the religious and the spiritual, complaining: “Men are grown mechanical in head and heart, as well as in hand.”48 He was criticizing not just literal machines but all of scientific and rational culture. Thoreau, writing around the same time, said that modern improvements were “an illusion” and that inventions were “pretty toys, which distract our attention from serious things”; he warned that “men have become the tools of their tools.” He famously promoted a minimalist lifestyle of acquiring only the bare necessities, in order to achieve true freedom.49 Tolstoy asserted that “progress has not so far improved, but it has rather rendered worse, the position of the majority, that is to say, of the workingman”: it had given him railways and cheap cloth, but it has also “brought his condition very near to slavery”; it had created art, music, and theater, but left these inaccessible to him. He thus saw all of the professions of science, art, engineering, and medicine as a fraud: claiming that they have “aided in the forward march of mankind,” he wrote, is like claiming that “an unskilled banging of oars … is assisting the movement of the ship.”50 Authors and poets added their criticism, from Mary Shelley’s vision of science creating hideous monsters, to Wordsworth’s warnings that industry is a “false utilitarian lure” and that in pursuing science, “we murder to dissect.”51

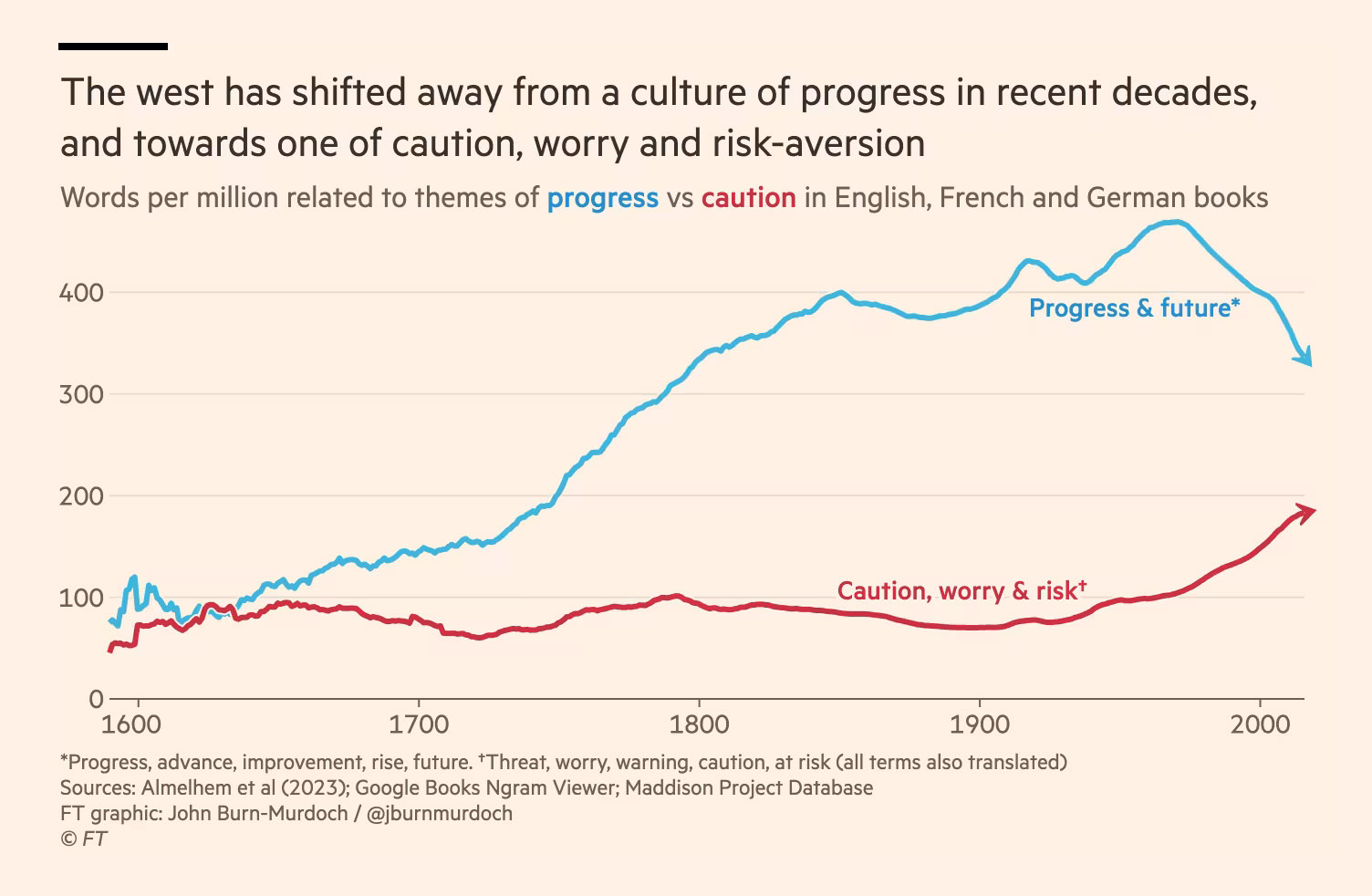

Through the 19th and early 20th century, voices like these had been in the background; if the intellectuals knew them, the common man could barely hear them above the sound of the parades and the fireworks for new bridges and inventions. One analysis of word frequencies in English, French, and German books shows that in the early 1600s, words related to progress and the future were about as common as words related to caution, worry, and risk; in the late 1800s, the latter themes had not increased, but themes of progress and the future were four times more common.52

The problems of the 20th century, however, gave critics of progress a new opportunity to come to the fore. The second response to the crisis of optimism, then, was a growing strain of anti-establishment thinking that criticized both the techno-industrial capitalism that had created material progress and the supposedly enlightened technocratic leaders who claimed to be protecting us from the problems of progress.

Those leaders had not solved the problem of war. War was still around, and it had become increasingly mechanized and technical. Philosopher John McDermott, writing in 1969, saw the Vietnam bombing program as the perfect example of the meaning and results of technology, a program “able to suppress the humanity of its rank-and-file and to commit genocide as a by-product of its rationality.” Advanced management techniques and industrial capital, including “enormous stocks of rockets, bombs, shells and bullets, in addition to tens of thousands of technical specialists; pilots, bombardiers, navigators, radar operators, computer programmers, accountants, engineers, electronic and mechanical technicians,” all came together so that “the farmers may be bombed according to the most advanced statistical models.”53 Lewis Mumford stressed the mutual reinforcement of industry and war: not only do technology and industry make war more destructive; war also motivates technological advances and industrial economies of scale: “war has been perhaps the chief propagator of the machine.”54

Nor had technocratic leaders taken care of the environment. Pollution and health hazards were still with us, and new hazards were being created all the time. Resources seemed to be dwindling—recall the fears of overpopulation and the “limits to growth” discussed in Chapter 7. In the early 20th century, environmental issues had been addressed with a technocratic conservationist mindset that sought to wisely manage resources for human purposes: in 1913, “preservationist” John Muir, who wanted to protect nature for its own sake, lost the fight against Hetch Hetchy Dam in Yosemite to conservationist Gifford Pinchot.55 But by mid-century, many more people believed in the intrinsic value of nature. Worries about pollution, health, and resources had melded into a general concern about “the environment,” a “mother nature” to be honored and obeyed.56 Stewart Brand says that the environmental movement has been driven by both romanticism and science;57 in the 20th century, the balance of power in the movement tipped to the romantics.

Further, the “scientific management” of the technocrats had become an oppressive, even authoritarian regime that robbed individuals and local communities of autonomy. As early as the 1910s, factory workers were affronted by Taylorism, which viewed them as simply parts of a machine. Taylor explicitly prioritized the system over the individual: “In the past, the man has been first; in the future the system must be first.” Workers protested, calling his time-and-motion studies “humiliating” and “un-American.” Samuel Gompers, the famous labor leader, once lambasted scientific management in a speech: “So, there you are, wage-workers in general, mere machines—considered industrially, of course. Hence, why should you not be standardized and your motion-power brought up to the highest possible perfection in all respects, including speeds? … Science would thus get the most out of you before you are sent to the junkpile.”

As anti-establishment thinking grew, it turned a skeptical eye on technocratic projects. Robert Moses, hero of New York, was criticized by Jane Jacobs and Robert Caro for overriding local control and the will of communities.58 Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring is remembered for warning of the dangers of pesticides such as DDT, but she was also criticizing the government programs that sprayed pesticides from airplanes on wide regions, even against local objections—literal top-down control.59

At the same time, the philosophers of the counterculture bemoaned the loss of what they called “freedom.” Herbert Marcuse “argued that the systems of production in modern capitalist and socialist societies repress the spirits and constrain the freedom of individuals”; Jacques Ellul “suggested that … the price we pay for a cornucopia of goods and services is slavery.” Charles Reich, in The Greening of America, wrote: “What we have is technology, organization, and administration out of control, running for their own sake. … And we have turned over to this system the control and direction of everything—the natural environment, our minds, our lives.”60

In identifying its antagonist, the counterculture did not distinguish between science, technology, industry, corporations, government, media, and universities—those institutions were all complicit together. Lewis Mumford called it “the megamachine,” saying that “to become the lords and possessors of nature was the ambition that secretly united the conquistador, the merchant adventurer and banker, the industrialist, and the scientist, radically different though their vocations and their purposes might seem.” (And in a perfect expression of fatalism and defeatism, Mumford described society using “the metaphor of an automobile, filled with passengers and without a steering wheel, rushing downhill toward an abyss.”)61

Technocracy had bundled progress and authoritarian control, and the counterculture opposed both, as a package. If the technocracy claimed that its authority was necessary to make progress, the counterculture rebelled against authority, and rebelled equally against progress. Ellul lamented the kinds of celebrations of progress common in the 19th century, writing that Sputniks “scarcely merit enthusiastic delirium,” and that “it is a matter of no real importance whether man succeeds in reaching the moon, or curing disease with antibiotics, or upping steel production. The search for truth and freedom are the higher goals….” He did not mean political freedom, but freedom from the forces of technology.62

Not all writers of the era rejected technology as such. Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog envisioned self-sustaining communities using small-scale “appropriate technology,” minimizing their dependence on large-scale infrastructure and systems. Energy policy writer Amory Lovins advocated turning away from the “hard path” of large, centralized power plants using fossil fuels and nuclear to serve a wide-area grid, and towards a “soft path” of small, decentralized generation from “sustainable” sources like wind and solar.63 But others embraced a more romantic view of nature and a more biocentric ethics. The “deep ecology” movement “freely criticizes so-called advanced technology and concepts of ‘progress,’” wrote philosopher Arne Naess. “The destruction now going on will not be cured by a technological fix.”64

Seeds of this thinking appear as early as the 1930s and ‘40s, in authors such as William Vogt and Lewis Mumford. By the 1960s, the counterculture was a major social force—but the US was still led by technocrats. But by the early 1970s, the credibility of technocracy had suffered an accumulation of blows, including the Watergate scandal, the oil crisis, and the growing opposition to the Vietnam War. By the mid-1970s, many people had decided that our leaders were unfit to govern, both practically and morally: they could not handle affairs either at home or abroad, and they were plagued by scandal. Trust in government, which polled at 77% in 1964, had fallen to 36% a decade later.65 Belief in progress, too, began to plummet: the same textual analysis showing the rise in themes of progress and the future before the mid-20th century shows a 25% drop in those words in recent decades, while at the same time themes of caution, worry and risk have plummeted:66

Skepticism of technocracy and of progress was soon embodied in regulation and activism. The technocracy had created federal agencies in the name of health and safety; the growing anti-establishment sentiment saw them as ineffective or corrupt, believing, in the words of one historian, that “those agencies were no longer representing the public interest and that citizen groups needed to force the government agencies to do the right thing.”67 Ralph Nader pioneered a strategy of “public interest law,” and he and his allies helped to create a “vetocracy” that empowered activists to slow, obstruct, and kill projects they saw as harmful.68 The motivation was explicit: a 1971 court ruling, enforcing the new National Environmental Policy Act against a proposed nuclear plant, stated that the recently enacted laws “attest to the commitment of the Government to control, at long last, the destructive engine of material ‘progress.’”69

And so we end up at today, and the situation I described in the introduction: where The Atlantic asks whether progress is good for humanity, and serious historians call agriculture a “mistake” or say that the idea of progress has been “refuted”; where the public believes that energy usage is “shameful,” and young people believe that “humanity is doomed”; where TFP growth has fallen by almost a factor of four, and our most prosperous states struggle to build even popular projects such as solar power or mass transit; where our planes fly slower and our rockets soar lower than they did over 50 years ago.

The 19th-century philosophy of progress was naive, perhaps hopelessly so. But the 20th century left us with something worse: fatalism, defeatism, and a hollowed-out vision of the future.

We need a new philosophy of progress for the 21st century. One that corrects the errors of the 20th: the naive optimism of the pre-war era, the attempt to achieve security through authoritarian control, the wholesale rejection of progress by the counterculture.

Techno-humanism is that philosophy. It reaffirms that progress is real, important, and good; that we have agency to solve problems and to shape our destiny. It paints an inspiring vision of the future: one where we cure disease and aging, expand our knowledge and abilities using AI, harness massive amounts of energy, and expand to the stars.

At the same time, it acknowledges that progress comes with costs and risks—pollution, health hazards, economic upheaval—and that moral progress does not automatically come with technology, which can be used to enable empire, wars of conquest, and totalitarian oppression. We must be solutionists, rather than complacent optimists or defeatist pessimists, about these problems.

In short, techno-humanism combines a deep belief in the power of science, technology, and industry together with a commitment to use those for the advancement of human well-being.

Progress is not automatic or inevitable. It does not unfold according to a divine plan or cosmic will. It requires choice and effort. Above all, progress requires that we believe in it. Techno-humanism is the foundation for restoring that belief.

Parts of this essay were adapted from “We Need a New Philosophy of Progress,” “The Lure of Technocracy,” and “From Technocracy to the Counterculture.”

1: Bury, Idea of Progress, 8–15.

2: Mokyr, Culture of Growth, 248; “Progress isn’t Natural.”

3: Mokyr, Culture of Growth, 153.

4: Bacon, Novum Organum, 47.

5: Bacon, Novum Organum, 39.

6: Mokyr, Culture of Growth, 101.

7: Condorcet, Outlines of an Historical View of the Human Mind, 279.

8: “Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, marquis de Condorcet”

9: Hughes, American Genesis, 246–7, 48.

10: Scott, Seeing Like a State, 87.

11: Hughes, American Genesis, 247.

12: Mencken, “Prejudices.”

13: Mann, Wizard & Prophet, 272.

14: Hughes, American Genesis, 355.

15: “Tennessee Valley Authority Act.”

16: Hughes, American Genesis, 269.

17: Stalin, “The Foundations of Leninism.”

18: There were regional conflicts and colonial wars, but no war between great powers. This period was called the “Belle Époque” in France and in Europe more broadly, and is remembered as a time of peace, prosperity, and “the feeling that progress was all-powerful” (Kalifa, The Belle Époque, Prologue).

19: Brazil was the last Western nation to abolish slavery, in 1888: Salles, “The Abolition of Brazilian Slavery, 1864–1888.”

20: Standage, Victorian Internet, 85.

21: Van Doren, The Idea of Progress, 30.

22: Spencer, Social Statistics, Chapter 2, Part 4.

23: Wells, The Discovery of the Future, 59.

24: Angell, Great Illusion, xii.

25: Nye Jr. and Welch, Understanding Global Conflict and Cooperation, 12.

26: Quoted by Bertha von Suttner in her 1905 Nobel acceptance speech. Von Suttner, “The Evolution of the Peace Movement”

27: Tertrais, “As Day Follows Night.”

28: “Andrew Carnegie’s New Year Greeting, 1914.”

29: Horn, “Machine-breaking in England and France during the Age of Revolution.”

30: Chase, Economy of Abundance, 14–19.

31: Mark Aldrich, Safety First, 76ff.

32: Devlin, “A Historical Review of ‘phossy jaw.’”

33: Reynolds and Neill, “Conditions in Chicago Stock Yards”; Beaver, “Population, Infant Mortality, and Milk.”

34: Hopkins Adams, “The Great American Fraud”; Ballentine, “Sulfanilamide Disaster.”

35: Pamboukian, “’Looking Radiant’: Science, Photography and the X-ray Craze of 1896.”

36: Haldane, “Daedalus, or Science and the Future. “

37: Becker, Progress and Power, 6.

38: Lippmann, Phantom Public, 38–9.

39: Lippmann, Public Opinion, 248.

40: Phantom Public, 61–2.

41: Phantom Public, 144, 68.

42: Bybee, “Can Democracy Survive in the Post-Factual Age?”

43: American Association for the Advancement of Science, “Trends in Nondefence R\&D Funding by Function.”

44: “FDA History”; “Securities and Exchange Commission Is Established”; “A Brief History of the FAA.”

45: National Archives, “Page Count by Category.”

46: Rousseau, “Discourse on the Arts and Sciences.”

47: Carlyle, “Midas”.

48: Carlyle, “Signs of the Times.”

49: Thoreau, Walden, 41, 57.

50: Tolstoy, On the Significance of Science and Art, Chapter IV.

51: Shelley, Frankenstein; Wordsworth, “On The Projected Kendal And Windermere Railway,” “The Tables Turned.” Note that elsewhere Wordsworth’s sentiment was more mixed, see for example “Steamboats, Viaducts and Railways.”

52: Burn-Murdoch, “Is the West Talking Itself into Decline?”

53: McDermott, “Technology: The Opiate of the Intellectuals.”

54: Mumford, Technics and Civilization, 86, more broadly see 81–94, 164–5; also Pentagon of Power, 239–41.

55: Smith, “The Value of a Tree: Public Debates of John Muir and Gifford Pinchot.”

56: See discussion in Chapter 2.

57: Brand, Whole Earth Discipline, 207.

58: Gopnik, “Jane Jacobs’s Street Smarts”; Caro, Power Broker.

59: Silent Spring, 54 ff.

60: Hughes, American Genesis, 446, 452; Reich, The Greening of America, 93.

61: Hughes, American Genesis, 448, 450.

62: Hughes, American Genesis, 452.

63: Hughes, American Genesis, 454.

64: Naess, “The Deep Ecology Movement.”

65: “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2024.”

66: Burn-Murdoch, “Is the West Talking Itself into Decline?” For commentary and further investigation into how much to trust this analysis, see Clancy, “The Decline in Writing About Progress.”

67: Gonzalez, “The Rise of Public Interest Advocacy.”

68: Klein, “Francis Fukuyama: America is in ‘one of the most severe political crises I have experienced.’”

69: “Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Committee v. US Atomic Energy Commission.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].