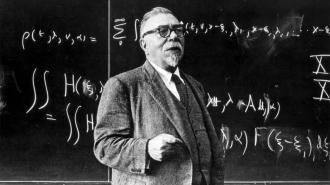

Long before Geoffrey Hinton and Eliezer Yudkowsky sounded warnings about artificial intelligence, there was Dr. Norbert Wiener in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Wiener was a pioneer in the field of artificial intelligence or, as he called it, cybernetics. His groundbreaking work laid the foundations that our current AI boom is built atop of, and his concerns about AI have no doubt influenced those being voiced by his successors in the field today.

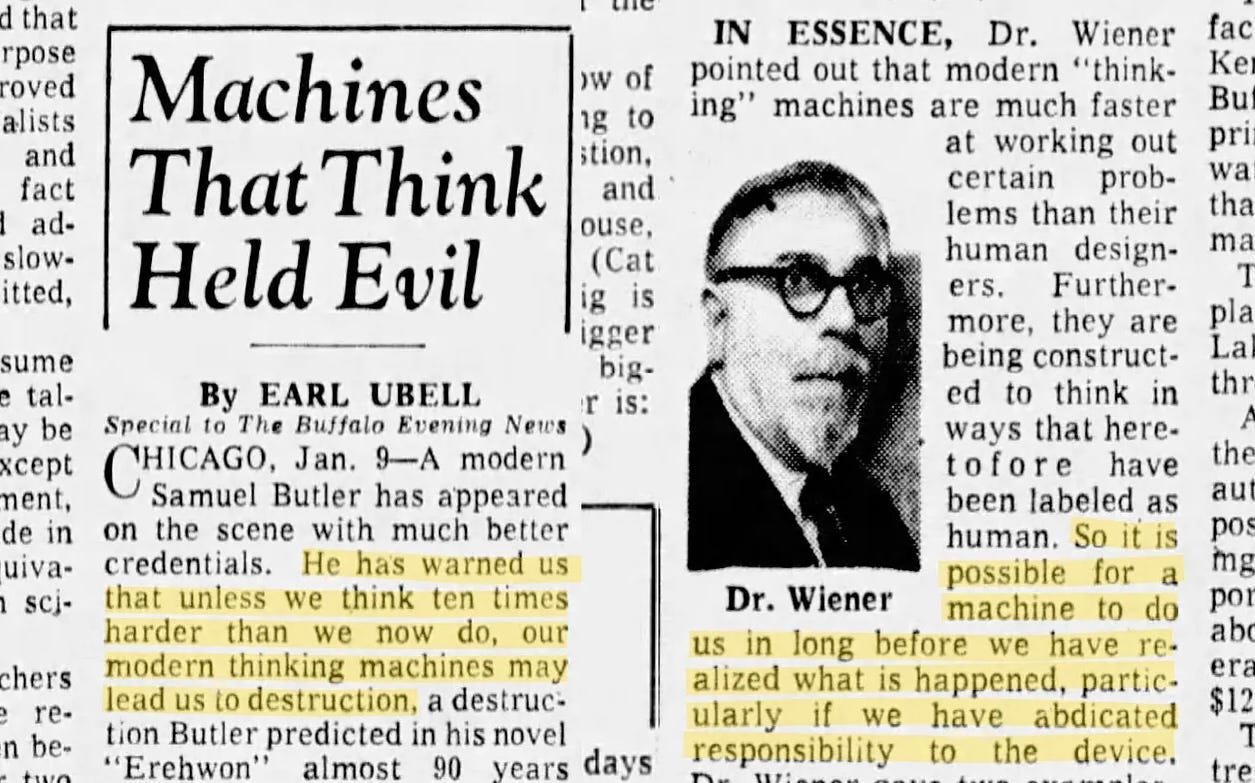

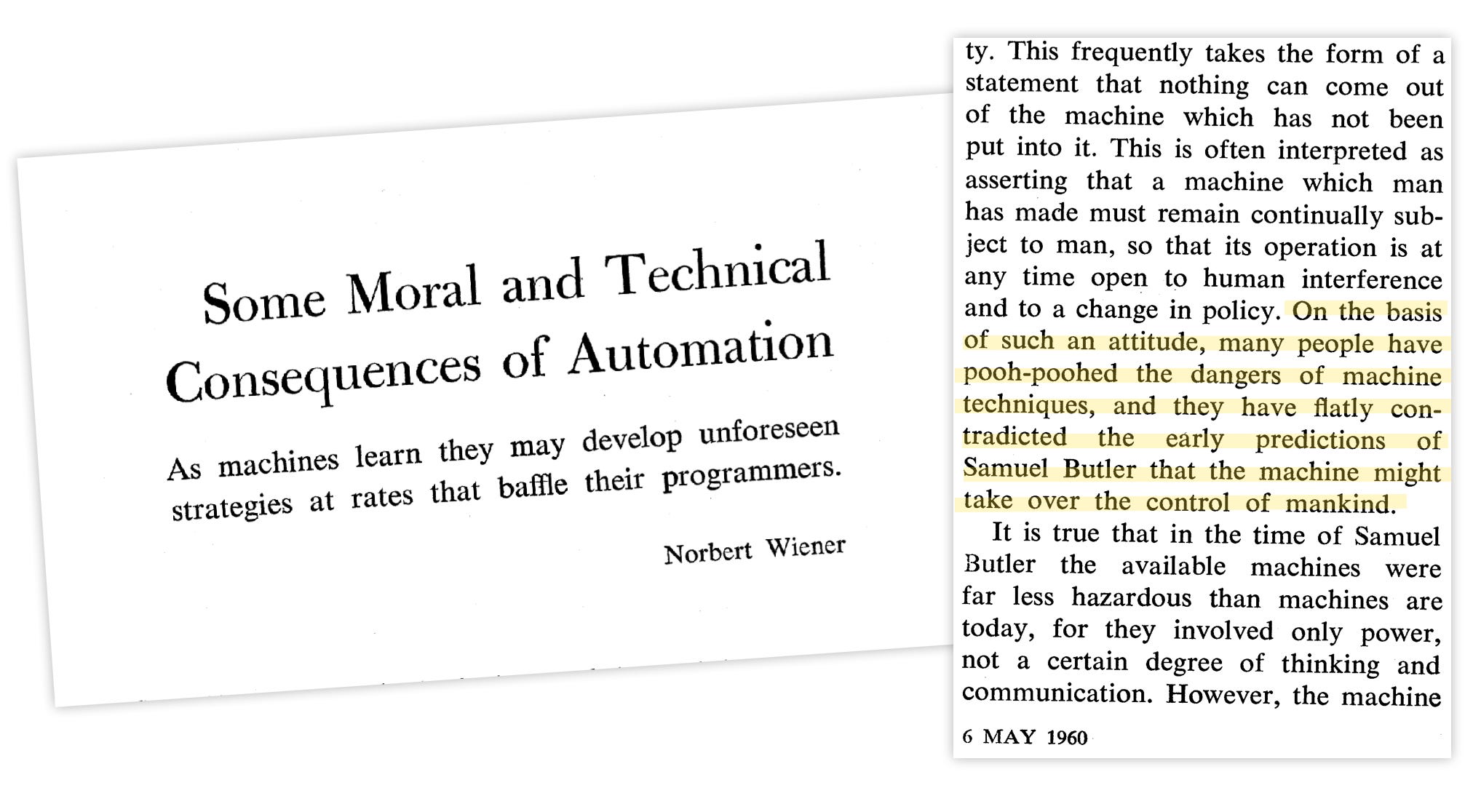

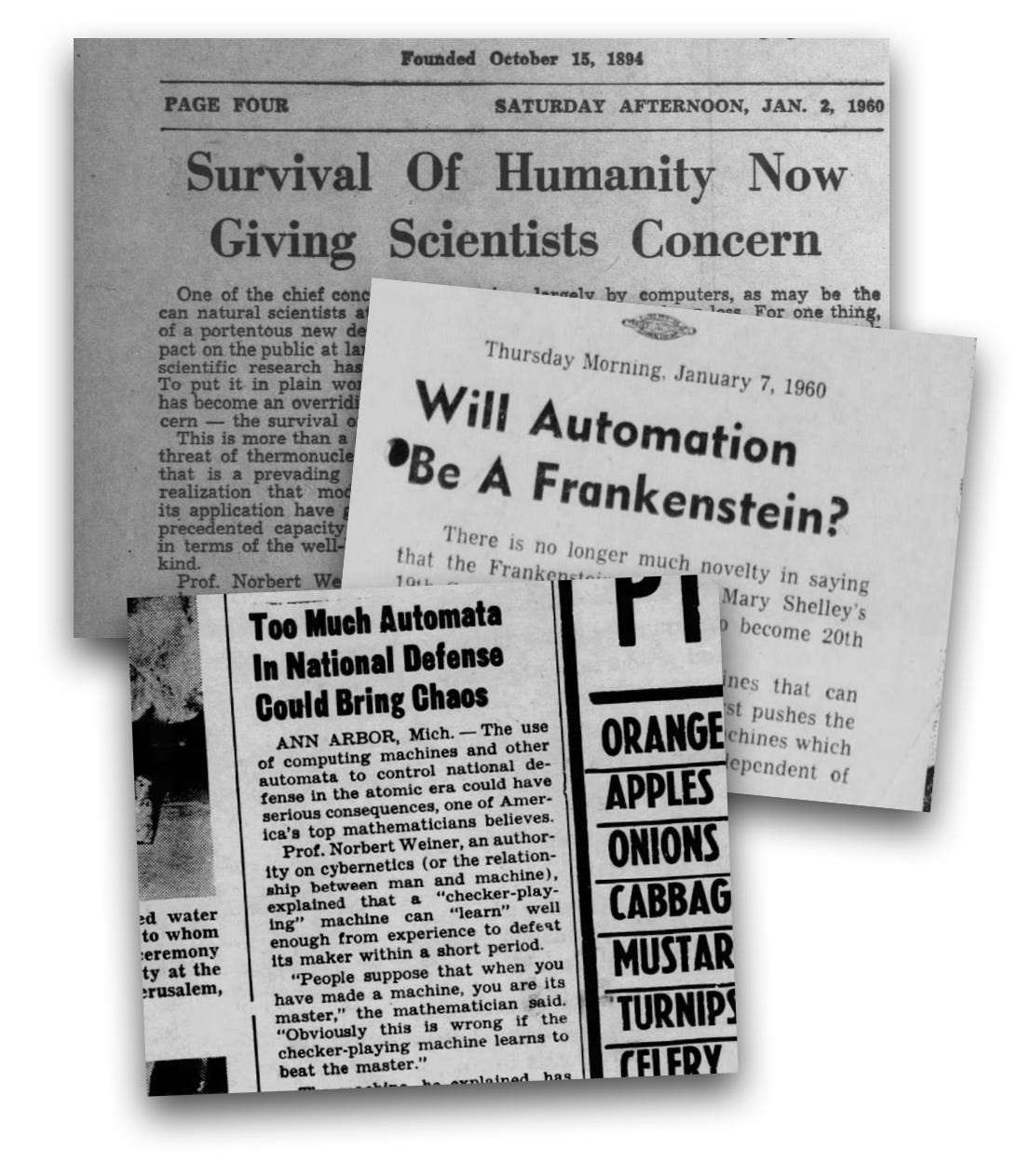

In late 1959, Wiener gave a speech to the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In early 1960, it would be adapted and published as a paper titled “Some Moral and Technical Consequences of Automation.” The speech began by citing the predictions of Samuel Butler in the 1860s, which foretold machines would eventually out-evolve and rule over man, noting they had not come to pass. However, he said it was different this time since machines had become so much more advanced at such a rapid pace.

Wiener observed that, generally, people wished slaves to be intelligent and subservient. However, “complete subservience and complete intelligence do not go together.” He’d posit that, like the philosopher slaves of Ancient Greece, machines would eventually outwit their masters: “If the machines become more and more efficient and operate at a higher and higher psychological level, the catastrophe foreseen by Butler of the dominance of the machine comes nearer and nearer.”

These scary predictions, from a pioneer in the field, were taken seriously and generated headlines, much like more recent concerns from AI experts have. Coverage of Wiener‘s warnings referred to him as a new, better-educated Samuel Butler. While Butler was a writer and cultural critic, Wiener was an expert and pioneer in computer science, so who were we — or anyone else — to question his well-informed prognostications?

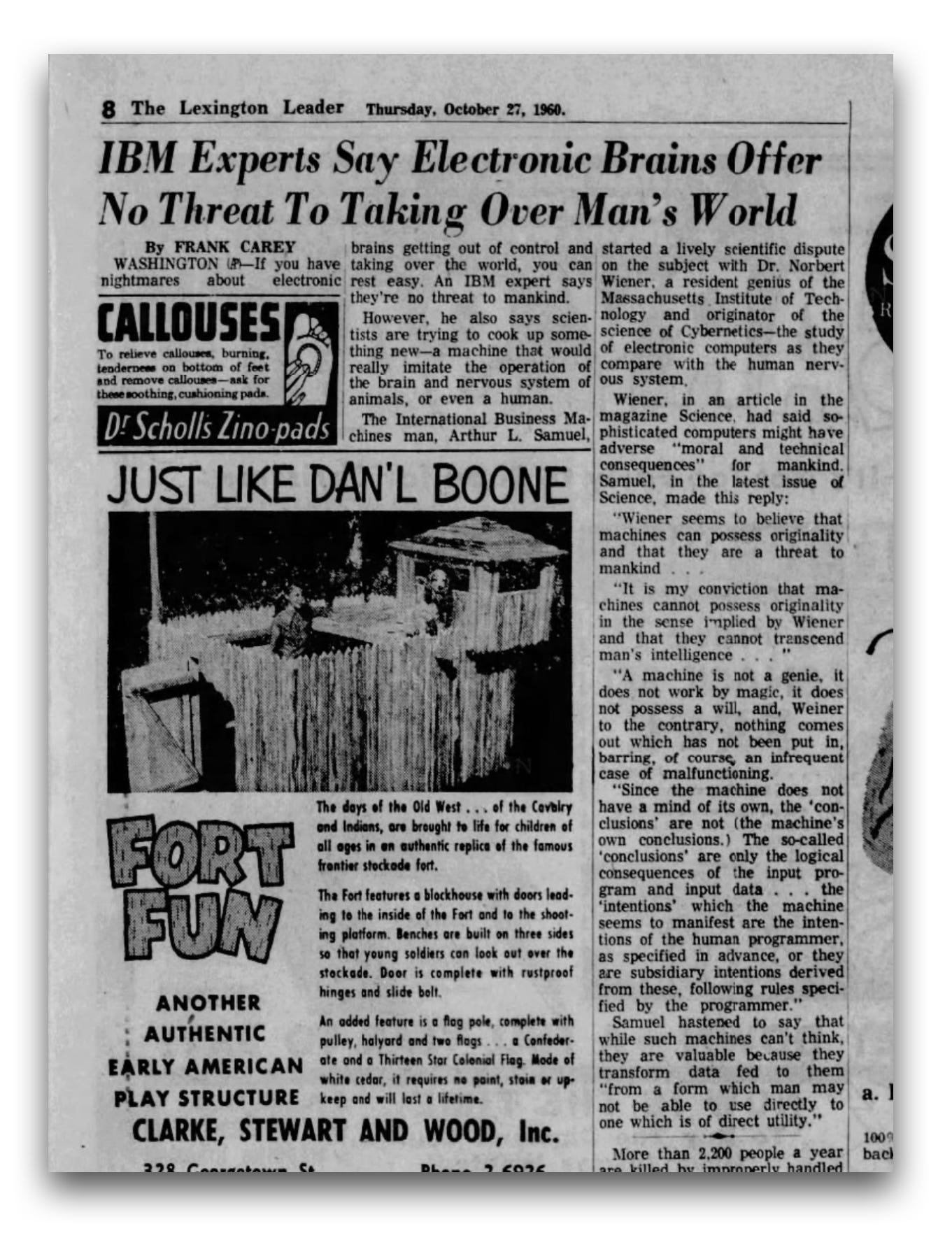

Larger players in the industry, such as IBM expert Arthur L. Samuel, would push back on this rhetoric, making Wiener appear like a conscientious Goliath versus a corporate David. Samuel’s retort to Wiener: “A machine is not a genie. It does not work by magic. It does not possess a will, and, Wiener, to the contrary, nothing comes out which has not been put in.”

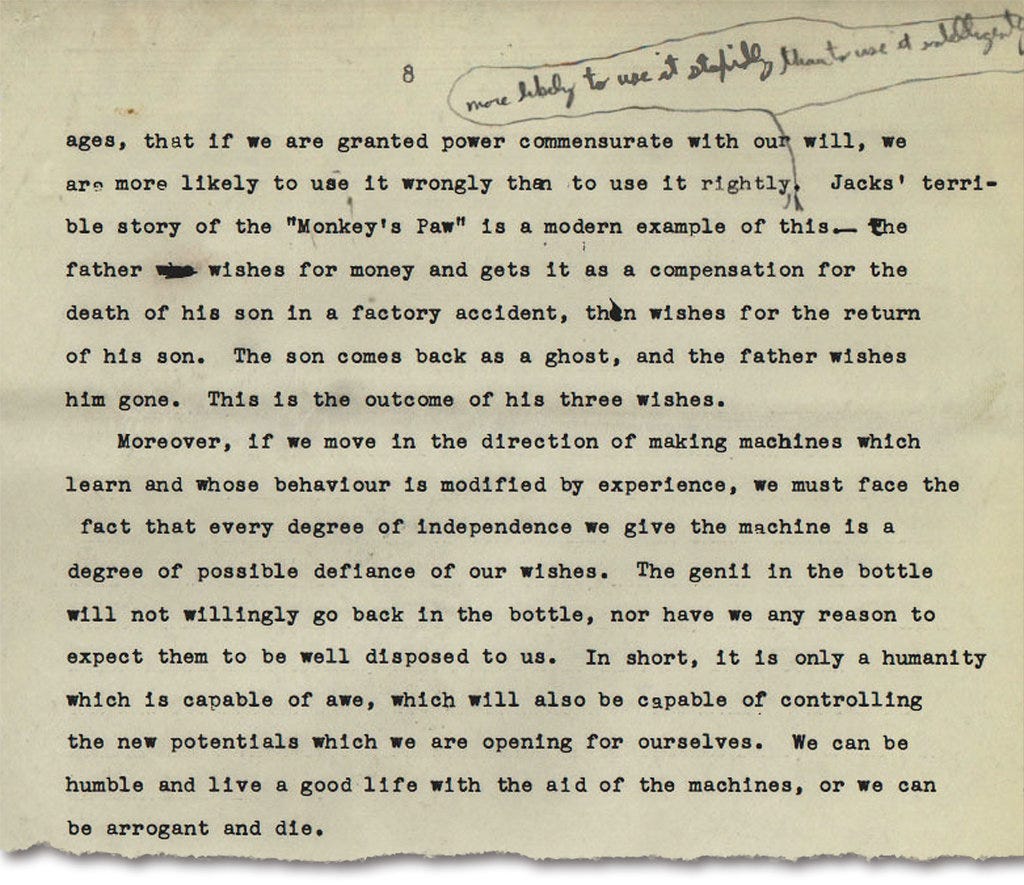

This wasn’t the first time Wiener had voiced concerns about thinking machines. A decade prior, his book “Cybernetics” (1948) would voice a number of dystopian predictions about AI. A year after its publication, in 1949, the editor of The New York Times asked Wiener to write an op-ed about “what the ultimate machine age is likely to be” exploring some of the key topics in the book. The first draft was rejected by the editor, who requested another draft, which was thankfully archived (unlike the first):

In the second draft, Wiener would cite old fables, such as genies in bottles, that he said contained a powerful lesson: If we have the power to realize our wishes, “we are more likely to use it wrongly than to use it rightly, more likely to use it stupidly than to use it intelligently.” His prediction, one familiar in the current dialog around AI: “The machines will do what we ask them to do and not what we ought to ask them to do.”

Wiener also predicted mass unemployment and an “industrial revolution of unmitigated cruelty” by making “possible the factory substantially without employees” — factories that could bankrupt their owners by taking orders too literally. He voiced similar concerns about autonomous weapons, too, which he said, “may produce a policy which will win a nominal victory on points at the cost of every interest we have at heart, even of national survival.”

His final line and parting message: “We can be humble and live a good life with the aid of the machines, or we can be arrogant and die.”

Three-quarters of a century on, the concerns and debates remain the same.

The editor of The New York Times would reject the second draft, too, requesting a copy of the first draft so the best of both could be combined into one piece. Wiener would decline the request, citing it would require an impractical amount of coordination, something unavoidable in a pre-internet age. If only they’d had the internet, Google Docs, and, even better, a large language model to help combine the first and second drafts, as we do 74 years later.

Three-quarters of a century on, the concerns and debates remain the same. While some experts like Yann LeCun push back and are labelled corporate stooges, others make wild prognostications, ones the press treat seriously. They are, in turn, heralded as new Samuel Butlers, as Norbert Wiener was. Wiener’s prophecies didn’t come true, like Samuel Butler’s before him, but this time — like last time — it is different.

This article was originally published on Pessimists Archive. It is reprinted with permission of the author.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].