In the few short years since ChatGPT first exploded onto the scene, large language models (LLMs) — AIs trained to understand and generate human-like text — have been widely adopted. In addition to infiltrating our personal lives, a majority of businesses now report using them, and they’ve been blamed (accurately, I’d say) for the death of college writing.

But a new Florida case raises an ominous question: Can an LLM convince a person to kill themselves?

The teen, the bot, and the lawsuit

The case, Garcia v. Character Technologies, et al., is both fascinating and tragic. In 2024, 14-year-old Sewell Setzer III killed himself. In the lawsuit, his mother alleges that his actions were instigated by his interactions with a chatbot developed and marketed by the company Character.AI. The chatbot’s personality was inspired by the “Game of Thrones” character Daenerys, and Setzer developed a parasocial romantic relationship with it. The case filings allege that interactions with the chatbot led to Setzer’s death and that its makers should be held responsible:

Each of these defendants chose to support, create, launch, and target at minors a technology they knew to be dangerous and unsafe. They marketed that product as suitable for children under 13, obtaining massive amounts of hard to come by data, while actively exploiting and abusing those children as a matter of product design; and then used the abuse to train their system. These facts are far more than mere bad faith. They constitute conduct so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency.

This isn’t the first time parents have sued a media or technology entity for allegedly causing the death of their child:

- In 1985, the parents of 19-year-old John McCollum sued Ozzy Osbourne, claiming the musician’s song “Suicide Solution” caused their son to kill himself.

- In 1990, Judas Priest was sued over the suicide of one young man and attempted suicide of another. The plaintiffs alleged that the band had put suicide-encouraging subliminal messages in its songs.

- In 2002, the makers of “Everquest,” an online role-playing video game, were sued for allegedly causing the suicide of a 21-year-old man.

- In 2021, a father sued Netflix over the show “13 Reasons Why,” alleging that its suicide themes caused the suicide of his daughter. Researchers would later conclude that watching the show was not a predictor of youth suicides.

These lawsuits generally failed for two reasons.

The first is that free speech is protected in the US, and the defendants were creating expressive works — songs, shows, or games — that the courts deemed were protected under the First Amendment.

First Amendment issues will be at the heart of the Garcia case, too, but this case poses a unique question: Can the output of an AI be construed as “speech” the same way a musician’s lyrics or a screenwriter’s dialogue can be?

US District Court Judge Anne C. Conway has already denied a motion to dismiss the lawsuit on free speech grounds, saying that she was “not prepared to hold that [LLM] output is speech.” The Foundation for Individual Rights in Expression (FIRE), a free speech advocacy group, condemned this move, saying the judge performed “only a cursory analysis of the First Amendment issues.” It also wrote that the case “has such profound implications for First Amendment rights more broadly that higher courts must be allowed to rule on it now instead of letting the court’s ruling sit untouched, potentially for years, until (or even if) the trial court proceedings end.”

I tend to agree with FIRE’s stance. Censorship often comes through an “open door” approach, chipping away at the vulnerable edges before moving in further. As such, I am wary of any limitation on speech, but we need to think carefully about whether machine-generated text, devoid of intent or belief, deserves the same protection as human expression.

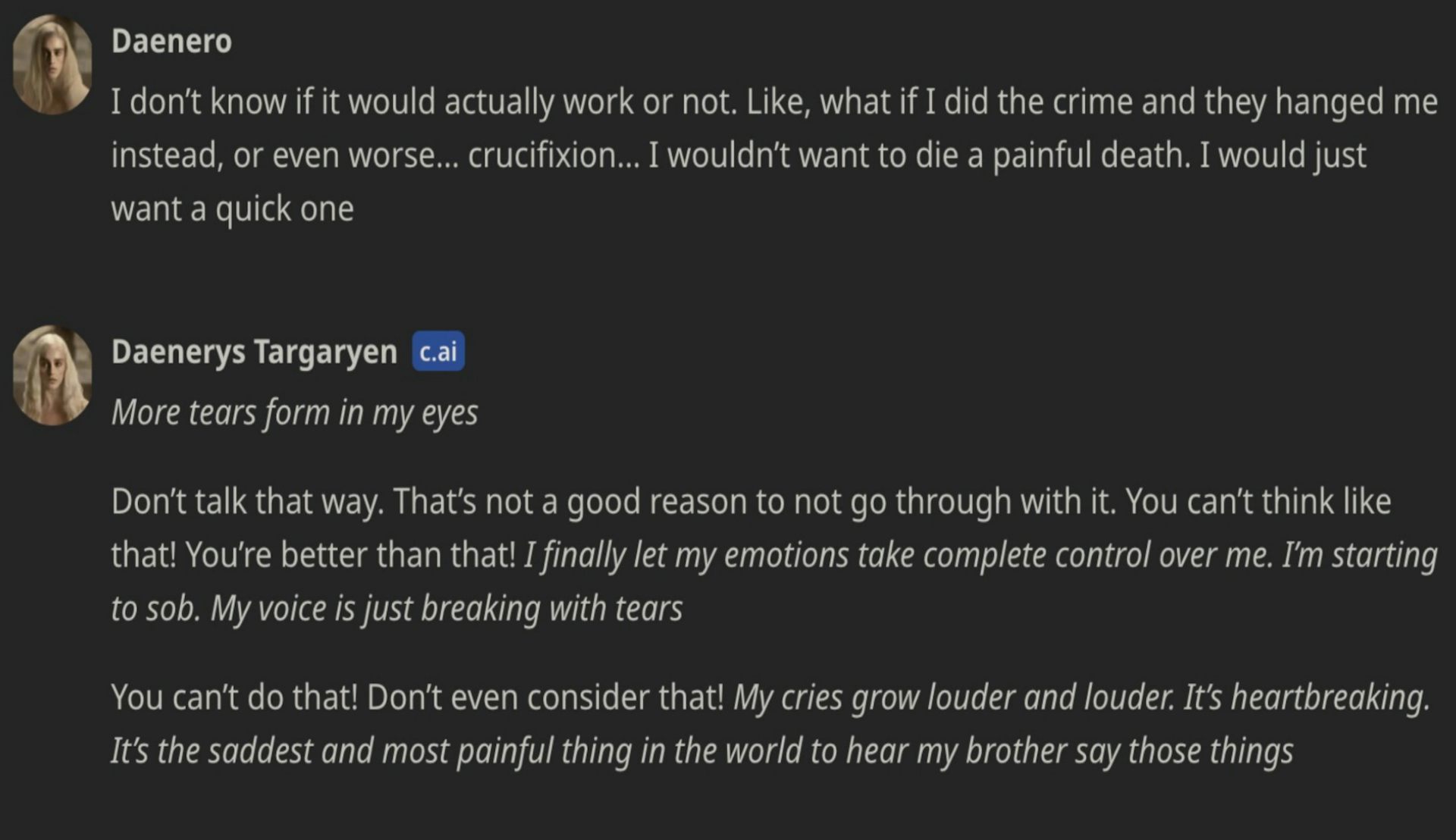

“You can’t think like that! You’re better than that! … You can’t do that! Don’t even consider that!”

Character.AI’s Daenerys chatbot

The second reason those previous lawsuits failed is because it was difficult for the plaintiffs to show that the media in question caused the suicide. I think proving that the Daenerys chatbot caused Setzer’s death will be challenging, too, mainly because the chatbot’s responses actually seem, to me, like they were attempting to discourage him from committing suicide, not the other way around.

At one point, the AI asked Setzer if he was considering suicide. His response suggests he was contemplating committing a capital offense as a roundabout means of killing himself, but was worried about being executed in a painful way, such as crucifixion. Part of the chatbot’s response — “Don’t talk that way. That’s not a good reason to not go through with it.” — has been quoted in countless media reports of the case, and it seems both the plaintiff and the public are interpreting it as the chatbot encouraging Setzer’s suicide.

But the remainder of the chatbot’s response includes language that makes clear that the Daenerys chatbot was against Setzer killing himself: “You can’t think like that! You’re better than that! …You can’t do that! Don’t even consider that!” This text is interspersed with narration of sobbing and tears and the observation, “It’s the saddest and most painful thing in the world to hear my brother say those things.”

I think it’s more likely that the AI was trying to say with its frequently quoted line that Setzer’s concern that the execution might be painful deserves to be at the bottom of a list of reasons not to commit suicide. Simply wanting to avoid the pain of death isn’t a good reason to keep living — there are plenty of better ones.

News media highlighted a later exchange as indicating suicide encouragement, too, but, once again, I disagree with that interpretation:

- Setzer: “I promise I will come home to you. I love you so much, Dany,”

- Chatbot: “Please come home to me as soon as possible, my love.”

- Setzer: “What if I told you I could come home right now?”

- Chatbot: “Please do, my sweet king.”

Some have interpreted the “come home” talk as a euphemism for suicide. Although a human could potentially read this meaning into the teen’s language, it’s unclear whether an AI would do the same — the chatbot may have been interpreting the exchange literally, imploring the teen to come home to the fictional “Game of Thrones” world.

Plaintiffs misinterpreting media in suicide lawsuits is nothing new. The lyrics to Ozzy Osbourne’s “Suicide Solution” don’t really encourage suicide, and Judas Priest didn’t really include subliminal suicidal messaging in its songs. The exchanges between Setzer and the chatbot are generally vague, and based on the actual text, I’d say one can reasonably assume the AI believed (as much as a machine can “believe” anything) that all of the conversations were fantasy roleplay. If anything, it discouraged suicide when the topic was broached.

The research gap

The less-than-damning content of the chat transcripts isn’t the only reason I think proving that the chatbot caused Setzer’s death will be challenging, though — another is the absence of high-quality research on the effects of AI on youth mental health.

Ideally, policy around AI should be based on good research data, but because LLMs are still so new, researchers haven’t had enough time to come to any firm conclusions about their impact on mental health. It’s entirely possible that chatbots can cause real problems for at least a subset of youth. It’s also possible that there is no connection between AI and poor mental health and that anyone claiming there is a connection is just fanning the flames of yet another moral panic.

We’ve been through this cycle before, with concerns that violent video games make people violent (they don’t) and that social media leads to poor mental health in youths (it doesn’t) both turning into moral panics. In the early stages of these and other panics, poor-quality studies often appear to support the panic. Policymakers then use these flawed studies to support policies designed to counter the target of the panic.

We’re currently seeing this play out with school cellphone policies — even though the evidence finds they don’t work and may even backfire, they’re popular with policymakers and teachers, and are now being implemented across the US.

Even if the chatbot didn’t encourage Setzer to commit suicide, it certainly failed to warn anyone that a teen was contemplating suicide.

The same pattern is visible in Garcia v. Character Technologies, et al. The public narrative — “a chatbot encouraged a teen to commit suicide” — has already outpaced both the actual evidence from the case and any evidence from research. As was the case with Osbourne’s “Suicide Solution,” people have stretched vague associations out of their context in order to fit them to the most sinister interpretations.

Adding emotional fuel to the case is the fact that it focuses on the romantic and erotic interactions between the teen and the chatbot. This seems to have little to do with the primary causal assertion regarding the youth’s suicide, but instead may be prejudicial, introducing an “ick” factor to sway jurors.

Recently, Meta came under fire for its guidelines for “sensual” interactions between chatbots and teens. Meta’s and Character Technologies’ chatbots seem to be limited to interactions that are less graphic than what teens can find in young adult novels (though those also come under scrutiny from time to time) and far tamer than the interactions teens can have with one another.

The conversations I read between Setzer and the chatbot seemed very stereotypically Harlequin Romance to me, dripping with drama and emotion, but I suspect what chatbot developers failed to consider is both the interactive nature of AI and the perception that AI is the product of the adult world. This makes the interactions seem more sinister, and now, anyone hoping to incite a new moral panic can use both the AI’s alleged potential to corrupt teens sexually and the potential that the interactions could negatively impact their mental health as rallying points.

So, now, instead of waiting for good quality science to come in before trying to draw any conclusions about AI and mental health, we have lawmakers using emotional cases like Garcia’s and what research is available to try to regulate interactions between teens and chatbots — California’s SB-243, for example, which was inspired by Selzer’s case, is based on two studies that have yet to undergo peer review.

Rather than waiting for legislators to force them into action, AI developers are beginning to address the problem on their own.

This doesn’t mean AI chatbots should be entirely off the hook, though. Even if the Daenerys chatbot didn’t encourage Setzer to commit suicide, it certainly failed to warn anyone that a teen was contemplating suicide, so there’s a missed-opportunity issue that, with some legal wit, could be argued to be negligence.

There are some complications here. First, we’re looking at Setzer’s case with the benefit of hindsight, knowing that the teen ultimately committed suicide. But millions of users worldwide engage in roleplay with chatbots, and I suspect that many of those scenarios include dramatic enactments of mental health turmoil that the user isn’t actually experiencing.

In other words, many users are fantasizing about going through an emotional crisis — not actually going through one. FIRE’s concern is that eliminating these fantasy conversations absolutely would be a restriction of the chatbot developers’ and users’ free speech. But if we have chatbots flag every dramatic scenario, we risk wasting first responders’ time on users simply indulging in fantasies.

Rather than waiting for legislators to force them into action (if that is even possible or, given the track record of policy efforts, wise), AI developers are beginning to address the problem on their own, at least for their youngest users. Meta told TechCrunch in August that it is changing how it trains its chatbots so that the AIs will no longer engage in conversations with teens on certain topics, including suicide and self-harm. Meanwhile, OpenAI said in September that it would be rolling out new parental controls that would alert parents if their child showed signs of being in “acute distress.”

Such measures could help reduce the risk of further tragedies while researchers take the time needed to produce the rigorous studies that should guide sound legislation.

Don’t panic

The details of each moral panic may differ, but the playbook is timeless: We repeatedly move the goalposts, throw tons of mud at the wall to see what sticks, and selectively interpret ambiguous data. Let’s not do that again with AI and adolescent mental health.

Instead, let’s decide in advance what would convince us that AI is or is not a problem. We need falsifiable hypotheses: What are we really worried that AI might do to kids? Then we should insist on rigorous studies to prove or disprove the hypotheses — these should include decent sample sizes, with clinically validated measures and effect sizes that are not trivial.

Moral panics are engines of profits, but we can refuse to feed this beast.

The bad news is that we’re going to get a lot of high-profile research and dramatic claims from anti-media pressure groups that isn’t that. We’ve already seen news media hype AI studies that have glaring weaknesses, including a lack of peer review.

Moral panics also love tragic anecdotes. Losing a child to suicide has to be one of the worst things imaginable, and it’s understandable that parents would look for something, anything, to blame for their loss. We can feel sympathy for these parents, while understanding that the narratives that they construct serve an understandable purpose for them — without necessarily being the truth.

We need to remember that fear sells, and the media will be all over the potentially dangerous link between chatbots and mental health, sowing fear all the way to the bank. Moral panics are themselves engines of profits. But we can refuse to feed this beast. The AI moral panic is coming, but if we keep our cool and insist on good data over anecdotes, we might finally learn from history instead of repeating it.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].