There’s one book about sports that gets brought up on almost weekly basis in Freethink’s office: David Epstein’s 2013 best-seller The Sports Gene.

Thoroughly reported and engaging, Epstein’s book explores human performance through a scientific lens, mows down countless sacred cows, and answers questions most people don’t ever think to ask about why and how human bodies work the way they do. Want to know why the best professional baseball sluggers always strike out against female softball pitchers? Or why world records for women’s track and field are stuck in the 1980s? The Sports Gene can tell you.

I found it to be so integral to understanding why some humans are better than others at various physical activities that interviewing Epstein for our Superhuman series felt like a no-brainer.

Freethink: After reading your book, I feel like my eyes have been opened to a bunch of dumb myths I previously believed. I’m also impressed that you were able to write about some hot-button issues without getting an aggressive pushback.

David Epstein: The reporting process taught me I was wrong about a lot of things, and I thought people were going to get really angry about the reporting on race and gender. But what actually made people angry was the stuff about the 10,000 hour rule (popularized by Malcolm Gladwell). I still get hate mail about that, which is not what I expected.

The 10,000-hour rule says that expertise in a given activity is the result of 10,000 hours of practice. On the one hand, that means you have to spend a lot of time practicing. On the other, it means if you spend that much time practicing, you’re all but guaranteed to be the best at that activity. But you provided data showing that the 10,000 hour rule doesn’t apply to everything and everyone.

Most people seem to be upset that I’m saying not everyone can do everything, but that’s what the research says. Maybe they’re having a reflexive reaction to everything in life not being within their control?

It does seem to be an American notion that if you work hard enough at something, you can be good at it.

I was a walk-on athlete in college, so I’m a huge believer in training. I think I can train literally anyone to complete a marathon in six months. I also think most people vastly underestimate how good they can get at most things, so it’s weird to become a spokesperson for the idea of “talent” as opposed to hard work.

My feeling is that you want to know which differences between people are real and not just folklore, bigotry, intuition, or whatever; you also want to know which of those differences matter for outcomes that we care about; and then how to work within the real world to get the optimal outcomes for individual people.

During the Rio Olympics, you participated in a forum for Outside about saving sports from doping. And it felt like a weird perspective shift. In the 1970s, steroids were having a huge impact on sports, but doctors said they didn’t work and thus didn’t affect sporting outcomes. Now there’s a recognition that they did affect sporting outcomes , but we’ve almost reached a point where we can say performance enhancing drugs aren’t having an outsized effect anymore because of our ability to test for them. That’s a huge shift.

It’s funny that you mention the medical community saying for a long time that steroids don’t work. I once wrote a story about a guy who sabotaged a seminal steroid study by buying the drugs off the study subjects. So this study reported no difference between placebo and treatment, while he was selling the treatment.

Imagine being a kid and saying you want to be an explorer, but the teacher pulls down the map and says, “Sorry, everything has already been found.”

But yeah, I think you’re right about the perspective shift. I’ve been following doping for a long time, and every time the World Anti-Doping Agency announced a new technological improvement in testing, it basically didn’t move the needle at all. The percentage of tests in any given sport that came back positive was still one to two percent worldwide. The dopers were basically in technological lockstep with the anti-dopers.

But recently I was able to read translations of the secret recordings made by the people involved in Russian state sponsored doping. Did you read about that?

Yeah, they were sneaking athletes’ samples through a hole in the wall of the testing facility.

Exactly! So I got to see these transcripts and I learned that the reason they hatched that plan to sneak stuff through the wall is that they thought they were not going to have positive tests because of the way they were doping, but people kept getting caught by the biological passport. Not everybody was getting caught, but more than they expected. That’s why they decided to do all that cloak-and-dagger stuff with the lab.

But usually, when there’s an organized effort like the biological passport, people find a way to get around the tests. So it was actually a positive sign to me that they felt they had to cut a hole in the wall of the lab. They weren’t consistently getting past the biological passport. That’s the first instance in the years I’ve covered doping that a country was genuinely worried about failing a doping test. I think that’s new. I’m not sure it’s going to continue, but it’s a big advance.

If you take two Olympic competitors, one with some sort of innate advantage and one without, and dope both of them, the person with the innate advantage still comes out on top. That’s probably true for the athlete who has access to better nutrition or better training equipment. Aptitude matters, but so do resources. Do you feel like the conversation about fair and unfair advantages should include things that aren’t related to drugs?

I think people are talking about that a little bit more, particularly since science has accelerated the differences. As major car companies get involved in events like bobsledding, not very many countries are even in the competitive pool anymore.

Like, the Cool Runnings story would be infinitely more difficult today (ed: Cool Runnings was a movie from the 1990s about Jamaica’s first-ever bobsleigh team competing in the 1988 Winter Olympics). The Cool Runnings team were actually having some decent runs. But you wouldn’t see that today because the technological gap is so huge.

Australia started to figure out the technical side for skeleton, a sport where you sled face-first. They took a beach sprinter who’d never done skeleton, and 18 months later had her competing in skeleton at the 2006 Winter Olympics. Then the Brits started thinking about skeleton that way, too. The last time I spoke to someone in Britain’s skeleton program, he said they’d figured out 80% of the science behind skeleton. They can select the ideal athlete for that event and get them Olympic-ready within a year. They can probably get them on the medal stand.

Now when I look at Olympic sports, I try to figure out which event has competitors from every populated continent. For Rio, I could come up with long jump and maybe the 1,500-meter race, which is a middle distance race. But for every other sport, you see maybe two or three continents represented, because of the technical advantage you now need to compete at a high level in most sports.

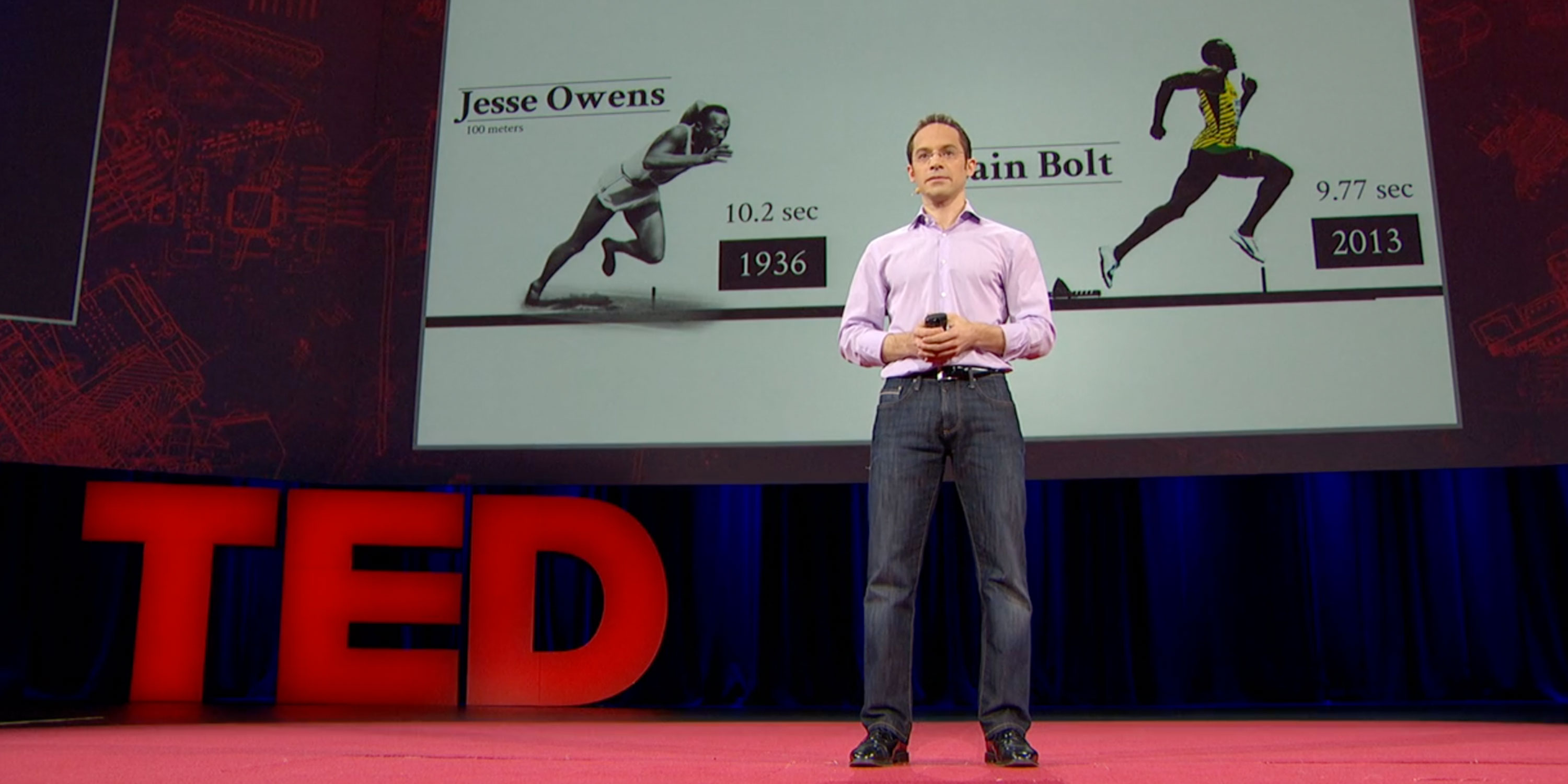

That focus on marginal performance improvements does raise the question of what we expect from sports. Like, we don’t just want to see people perform well or even win medals, we want to see all-time, record-breaking performances. What are the odds we’re approaching the ceiling for international sporting records?

I think improved drug testing has already capped the performances in a lot of events in women’s track and field, Most of the records for those events date back to the 1980s when there was a ton of doping and no effective testing. If you look at women’s track and field events today, even with training methods getting better and many more women coming into the training population, the world records for women’s track and field remain completely untouchable.

Lorenzo Cain was the best player on a team that won the World Series last year, and he didn’t start playing baseball until he was 16.

In other sports, like in swimming, the technological changes make a bigger difference than the athlete changes. Every time there’s a pool innovation, the records in swimming come down in these punctuated drops, as opposed to something gradual. The introduction of the flip-turn created one of these drops, and then when gutters were added to the sides of the pool to give turbulence somewhere to go, that caused another drop. And then pools started getting deeper to minimize turbulence in the lanes, and then they started calibrating the temperatures in the pools. So I think we’ll keep seeing world records in swimming, but it’ll largely be because there’s still technological opportunities to improve the pool.

As we get closer and closer to the limits of what’s possible, we’re not only going to keep experiencing diminishing returns, but the design of the course is going to matter more than the athletes.

Would you put Ryan Lochte’s maneuver of staying under for longer in that realm of technical improvements?

I would. And there’s also the huge ones, like the Fosbury Flop, which shows that skill changes also then cause a change in the competitive population. The Fosbury Flop changed the advantage from being able to get higher off the ground to having a high center of mass. Within two Olympics cycles, the average high jumper was five inches taller.

That’s happened in Tennis, too. As rackets have gotten lighter and the game has become focused on power serves, players have gotten taller and their limbs have gotten longer. So sometimes technological changes advantage or disadvantage people with certain physiological traits.

That reminds me of Bill Simmons’ argument in the Book of Basketball that there are NBA legends from the 60s, 70s, and 80s who wouldn’t be superstars today, not just because of rule changes, but because players are bigger and stronger. There’s something exciting about the idea that sports can improve organically over time, but it’s also weird that we’re obsessed with asking athletes to constantly get better.

I have to say that I understand why people who tune in for big events want to see records broken, but on a granular level, that falls by the wayside. With the athletes I follow in track, I want to know if they’re going to make the Olympics at all, if they’re going to make the finals. I want to watch how they run. And record races can actually be pretty boring. There’s no drama in watching someone blow the rest of the field away.

Records in sports are really only a early-to-mid 20th century thing. It happened really fast, and then it slowed down really fast. It’s far from a linear trajectory, and we’re way into the flat part of the curve in most sports.

The imposition of superlatives on sports does kind of diminish the other things that sports are good for, personal health and keeping kids out of trouble. What do we lose by obsessing at being the best as opposed to promoting those other benefits?

Imagine being a kid and saying you want to be an explorer, but the teacher pulls down the map and says, ‘Sorry, everything has already been found.’ I love high performance, but I do get concerned that we don’t put our money where our mouth is with these things we claim to most value about sports. Youth sports in particular are becoming more and more exclusionary. We’re trying to do selection of kids when they’re five years old.

I know the AAU system has been integral to the last couple generations of NBA caliber talent, but it’s disconcerting that we tell kids that they’re “too late” if they start playing a sport at age 13 as opposed to years earlier.

Totally. And for a lot of kids, early specialization is not even the right thing to do for skill acquisition.

In something like golf, for example, early specialization does work. But for sports that require more dynamic action and interpretation, having a more diverse experience–even within a single sport–is probably better. Which is the approach they take with kids and soccer in Brazil. You’ll see kids practicing on cobblestone in a narrow alley, and so the field is a different shape and the ball doesn’t work the same way as it would in a game. And that’s totally the opposite of what I see when I go to really technical youth soccer training camps in the United States.

It makes me think of Joel Embiid, who’ll be playing his first season of pro basketball for the Sixers this year. When he was drafted, all anybody could say was that it was crazy how good he was considering that he’d mostly played soccer. But after reading your book, I realized he was probably good at basketball because he’d played soccer, not despite the fact.

And nobody ever touts those stories! Lorenzo Cain was the best player on a team that won the World Series last year, and he didn’t start playing baseball until he was 16. Nobody even mentions it, because it doesn’t fit into the easy narrative we have about what makes someone good at a given sport.

In that vein, I was hoping we could close out with the finding in your book that surprised you the most.

One part that really surprised me was the work on voluntary physical activity. I knew that physical activity we undertake can have really profound effects on dopamine and other chemical messaging systems in the body, but I didn’t know there was this big body of work showing that the reverse is true: That your physiology partially determines the kind of physical activity you find the most rewarding and the most enjoyable to do.

(Y)our physiology partially determines the kind of physical activity you find the most rewarding and the most enjoyable to do.

I was surprised to see all the evidence supporting the idea that it’s a two-way system, and that it’s modifiable to a certain extent.

But the biggest revelation is the one I started the book with, which is the idea of perceptual expertise. The open secret of the book is that it’s just 15 open questions about the balance between nurture and nature in sports. And when I saw Jenny Finch pitch to Major League Baseball players, and 63 miles per hour flashed on the screen, I figured they should be hitting her pitches with no problem, but they weren’t, and I just couldn’t figure out why.

Diving into that, the answer wasn’t what I was expected. But now I see that explanation in play everywhere.

Homepage and feature image from Flickr