The bottom fell out of the video game industry last year, though you’d be forgiven if you find that news surprising.

Just two years prior, the industry earned an estimated $184 billion in revenue. That’s more than the music industry and global box office combined. Around 60% of Americans play video games, and while teen boys are still the most likely to identify as gamers, the average player is 36 years old and has been stomping goombas and throwing hadokens for 17 years. Even video game movie adaptations haven’t been that bad lately.

All of this points to the fact that, despite their humble, hobbyist origins, video games have become an economic force and cultural touchpoint in the 21st century. Why the rough times, then?

Economic headwinds, for a start. The industry defied expectations and grew steadily during the 2008 recession and the 2020 pandemic. These feats led some to herald video games as recession-proof. However, post-pandemic woes and the call of the outdoors after lockdown led to slumping sales in a long-overdue market correction.

Those sales slumps couldn’t have come at a worse time, either, as rising development costs are plaguing studios.

“Game design is often no longer predominantly the task of crafting challenges that elicit joy, delight, and surprise.”

Simon Parkin

While prestige titles like Call of Duty, Final Fantasy, and God of War, known in the industry as “AAA games,” make millions in revenue, they also cost millions to make. Activision’s Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War (2020), for instance, had a development price tag of around $700 million. That figure is double some of the most expensive movies ever made, and it doesn’t even account for the marketing budget.

To improve the odds of recouping such investments, publishers are increasingly turning to games as a service. This model seeks to continually monetize a game after its initial launch or sale through practices such as subscriptions, season passes, microtransactions, and various (occasionally scammy) blockchain hijinks. The strategy can be a windfall for any game lucky enough to strike a chord with a large audience, but disastrous for anything less than a hit.

“Game design is often no longer predominantly the task of crafting challenges that elicit joy, delight, and surprise (or the noblest of creative goals, encouraging people to see the world from an unfamiliar perspective),” journalist Simon Parkin wrote in an op-ed for the New York Times. “It is primarily the job of building machines to keep players engrossed and spending, in many cases, by grinding out repetitive tasks rather than ones that encourage creative or exploratory play.”

Pair these trends with high investor expectations and an increasingly saturated market, and it didn’t take a financial prophet to see hard times coming. Between 2023 and 2024, the video game industry laid off an estimated 25,000 people, and several studios shuttered their doors. An inventive, well-regarded game with healthy sales is no longer a guarantee of survival. Today, success must be stratospheric.

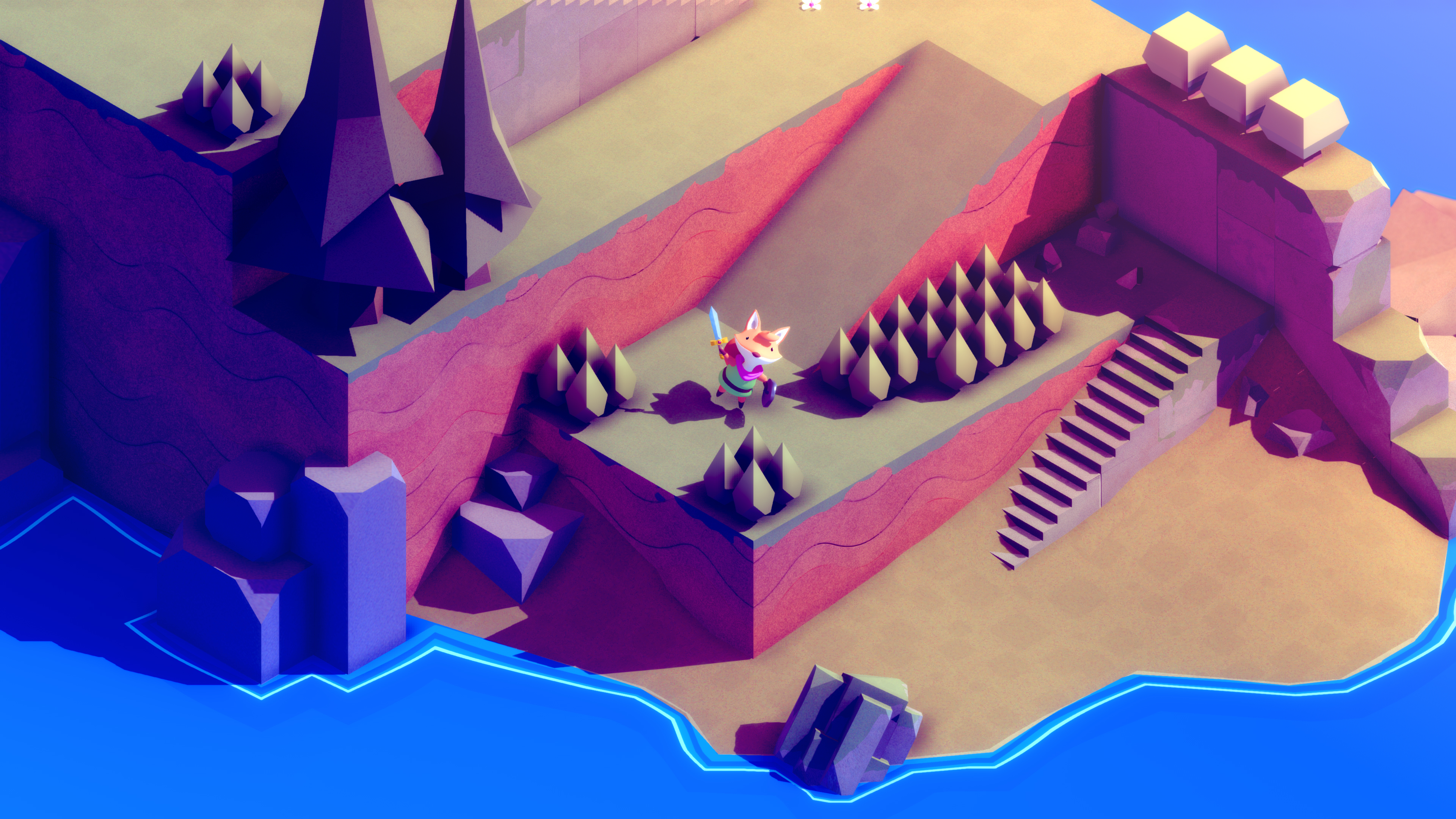

If there’s a silver lining, it’s to be found in the industry’s indie space.

Indie developers push the medium forward as big-name publishers focus on safe bets.

Independent developers are crafting smaller, more economically viable games that are not only experiencing commercial success, but also garnering recognition as some of the best games of their respective release years — or even as stone-cold classics worthy of a place in the pantheon of Mario and Sonic.

Perhaps more importantly, these developers continue to push the medium forward as big-name publishers focus on safe bets and machine-pressed sequels.

This turn of events is the result of the right technologies reaching the hands of a culture of passionate creators who were willing to take risks to share their visions with players worldwide. However, the indie scene is not isolated from the larger industry, and the very trends and technologies that raised it up may now threaten its future.

A short history of early indie games

Deciding who qualifies as an indie developer isn’t an exact science. For many, indie games are made by small teams with equally small budgets (though how small is up for debate). Others don’t care about size as long as the developer isn’t bound to outside stakeholders, and for some, being “indie” is more about style or vibe than anything else.

Ultimately, the boundary is breathable, and the distinguishing mark is more a communal spirit of creativity and experimentation than something calculated. Or, as Christian Tuttle, the solo developer who founded Imaginary Game Studios, told Freethink, “I think what many people call ‘indie development’ now is just what game development was in the past.”

From this viewpoint, the rise of the indies is the story of video games coming full circle, as that creative spirit was certainly the force that energized gaming’s early hobbyists.

Back when the arcades were booming and the first gaming consoles were finding their way to market, a subculture of garage programmers began using their state-of-the-art VIC-20s and PMC-80s to homebrew original video games. They designed sports simulators, Dungeons and Dragons-inspired adventures, and any other experience they wanted to try but couldn’t get elsewhere. They then shared their creations with one another.

Many programmers were content simply to shuffle cassettes between friends or pin diskettes to the dorm’s community corkboard, but the more entrepreneurial among them began to sell their creations. They offered mail-order delivery through ads. Gamer magazines featured “type-in software” articles, which, as the name suggests, provided a series of instructions readers could hard-code into their home computers to build a game. A really industrious programmer might have even distributed their game over radio waves.

As the subculture grew, the industry’s big players took notice. Atari, for example, began an exchange program through which programmers could submit video games and other software for inclusion in quarterly catalogs. A particularly popular title might even be bought and released on a home console.

But by 1983, Atari and other companies had flooded the US market with a torrent of titles, many of them shoddy cash grabs. Customers grew irritated, and the hobby’s popularity plummeted. While video games remained fashionable in other countries, the industry wouldn’t dig out of the New Mexico landfill Atari buried it in until Nintendo’s US launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) several years later.

“Atari collapsed because they gave too much freedom to third-party developers and the market was swamped with rubbish games.”

Hiroshi Yamauchi

Not about to repeat the mistakes of the past, Nintendo exerted tight quality control.

It was picky about which studios received development kits and limited how many games a publisher could release each year. The console’s hardware featured a lockout chip that prevented third parties from developing games for the system without approval, meaning publishers had to purchase cartridges directly from Nintendo. The company also protected its technology and branding with litigious zeal.

“Atari collapsed because they gave too much freedom to third-party developers and the market was swamped with rubbish games,” Hiroshi Yamauchi, Nintendo’s then-president, told The Vindicator in 1986.

The strategy worked.

While the NES hosted plenty of stinkers (as anyone who recalls the ominous letters LJN can attest), the Nintendo Seal of Quality reinvigorated the industry’s tarnished reputation, and console gaming entered its golden era. Sega followed Nintendo into the US market, first with the Master System (1986) and later the Genesis (1989). Nintendo released the Super Nintendo (1991) and the Nintendo 64 (1996). Sony then transformed the industry again with the wildly popular PlayStation (1994).

An unfortunate side effect of this era, however, was the marginalization of smaller studios, which often lacked the resources needed to market and publish games on physical media. They also couldn’t compete with bigger studios when it came to bargaining with console makers for development kits or retail chains for shelf space.

“The early 2000s was a very difficult time for smaller dev companies.”

John Baez

With the barriers to entry set so high, big-name publishers became the industry keyholders. To minimize risk and maximize profit, these companies often relegated smaller studios in their orbit to supportive roles, tasking them with porting games or handling licensed titles.

“The early 2000s was a very difficult time for smaller dev companies because there wasn’t a full-blown indie scene yet,” John Baez, co-founder of indie game studio The Behemoth, told Freethink. “[D]isk-based distribution required a publisher, and they only funded known dev teams.”

The indie spirit lived on, however, in the modding scene.

In 1994, computer programmer Brendon Wyber released a public version of the Doom Editing Utility, which allowed fans to create and share their own Doom levels. Team Fortress (1999) began life as a mod for Quake (1996) before Valve hired the creators to port their work to the company’s own engine.

And with Adobe Flash, just about anyone could create games and animations that could then be shared across user-generated content sites, such as The Behemoth co-founder Tom Fulp’s Newgrounds, which became the Greenwich Village of early internet culture.

Many of today’s indie developers began building their skills during this time.

Adam Saltsman, co-founder of collaborative game studio Finji, designed Canabalt (2009) in Flash and created an open-source game library called Flixel to help others make games with the software. The Behemoth’s Alien Hominid (2002) was also a Flash original before being redesigned for the PlayStation 2 in 2004 — it then became one of the first indie-developed games to find major success on a home console.

“I didn’t think of us as indie — I just thought of us as a very small development studio driven to create something special because otherwise we’d have to look for a job at another company,” Baez told Freethink.

“The new wave of game engines has been an absolute boon.”

Eric Studer

The year after The Behemoth’s watershed release was something of a turning point for indie games. Unity Technologies put out its namesake game engine, giving anyone with a computer and enthusiasm the ability to design a game at little cost. RPG Maker, another popular game-making engine, toured outside of Japan for the first time.

“The new wave of game engines has been an absolute boon,” Eric Studer, senior producer at Turning Wheel Games, the six-person indie studio behind Barony (2015), told Freethink. “It kind of brings things back to the days of just two guys in the garage [making games].”

Valve also retrofitted its software client, Steam, into a digital storefront and distribution platform in 2005. The first indie games on offer were Darwinia and Ragdoll Kung Fu, and while those are more curios than classics today, they kickstarted a trend. Thousands of games are now released on the Steam platform every year, and many are independently developed.

“Back in the day, even if you created an indie game, there was no way to distribute it on platforms like Steam,” Shunji Mizutani, executive producer at Playism, an indie-focused publisher, told Freethink. “So, when that became possible, it presented such a huge and valuable opportunity to indie developers.”

Recognizing that opportunity, Microsoft built the Xbox Live Arcade, a digital marketplace for Xbox games, and promoted the service through the Summer of Arcade. During that annual series, which ran from 2008–13, Xbox would release and promote five digital-only marquee titles, and many indie creations made the cut.

The first summer featured designer Jonathan Blow’s Braid and The Behemoth’s Castle Crashers. Both titles were well received by critics and players and went on to become classics of that generation. Later Summers would highlight such indie darlings as Limbo (Playdead, 2010), Bastion (Supergiant Games, 2011), Dust: An Elysian Tail (Humble Hearts LLC, 2012), and Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons (Starbreeze Studios, 2013).

Not only did the Summer of Arcade series showcase how small teams and solo developers could design unique and engaging experiences, but the featured games also helped shape the indie style, put promising development teams on the map, and set new expectations for an already-ossifying AAA scene.

“Microsoft was able to prove that gamers were willing to download games directly onto their Xbox 360s,” said Baez. “After that, the landscape for indie development completely changed.”

A new challenge approaches

By 2011, the indie game scene had entered its own golden era.

The hardware and software necessary to design games was more powerful and widely available than ever before — notably, Epic Games had unlocked its Unreal engine in 2009, releasing a free version of its award-winning development kit for hobbyists and indie developers.

Online distribution meant indie developers didn’t have to fight for limited shelf space. They could deliver and market their games directly to players. Seeing that success, the very keyholders of the 1990s and early 2000s unlocked the gates and threw them wide open for indies.

However, the tools and trends that gave rise to today’s robust indie game development scene have also created challenges, including the one hinted at during our short history tour: Players are now inundated with video games.

“Even if we manage to create a lot of buzz for our game, it gets drowned out in a matter of days.”

Shunji Mizutani

Today, Steam serves as a sort of worldwide dorm corkboard where professionals, students, and hobbyists can all share their passion projects. In 2024 alone, nearly 19,000 games were released on it, and it’s not the only distribution platform, either — even more games can be found on itch.io and other websites.

This means that shelf space is no longer the barrier to entry into the gaming industry. Player attention is. Simply getting people to notice your game exists can be a significant undertaking for an established indie studio, to say nothing of an up-and-comer.

“It’s incredibly hard these days because of the sheer amount of new information constantly becoming available,” said Mizutani. “Even if we manage to create a lot of buzz for our game, it gets drowned out in a matter of days.”

The digital nature of these gaming platforms also makes them susceptible to bad actors who further crowd the online space with thousands of “shovelware” titles — low-quality games made with cheap assets and then “shoveled out” to make a hasty buck — and scammy games that host malware and are made from stolen assets.

While Valve has worked to crack down on these bad actors, the trend of many bad games drowning out the good ones has unsettling echoes with the pre-’83 crash, and unlike AAA studios, which can cut through the noise with gigantic marketing teams, indie developers often go it alone.

“It isn’t for the faint of heart. It’s hard and getting harder,” Tuttle told Freethink. “You’ll spend a lot of time and money and get nowhere fast, but you have to keep trying anyway. This part of indie game development will drive you to a therapy office the quickest.”

“One of the biggest challenges is that you can’t do everything.”

Hiroyuki Kobayashi

As is their way, indie developers have to get creative.

One tactic is to take advantage of the infrastructure built by the industry’s big players. For instance, Binary Haze Interactive marketed its most recent release, Ender Magnolia (2025), by giving away its previous game, Ender Lilies (2021), through PlayStation Plus. This had the added benefit of strengthening the brand in Europe, where the PlayStation is incredibly popular.

“One of the biggest challenges is [that], within such a limited time and number of people, you can’t do everything,” Hiroyuki Kobayashi, Binary Haze Interactive’s CEO and creative director, told Freethink. “There’s so many ideas floating around, so it’s really important to decide what you’re not going to do and focus on improving the quality of the things that you are going to do.”

Another way to spread the word is to go directly to the players. Indie developers are a common sight at convention booths, on Discord channels, and on social media through YouTube videos and Reddit AMAs.

“We don’t have this massive network or infrastructure of people whose only job it is to deal with these relationships,” said Studer. “You have to do it yourself.”

“We’re providing a product that represents a relationship with our customers,” added Studer’s colleague Josiah Colborn, who serves as the creative lead at Turning Wheel. “They can come to us and talk about [our game]. We’re accessible. [They can] ask us questions or receive ideas or whatever. That’s just something you don’t get with a AAA studio.”

Still, the big challenge, as always, is money.

“I wish I could paint a prettier picture here, but indie game development isn’t something you get into for the money,” said Tuttle. “Making video games is like being a musician — you don’t get into it just because you want to. It’s something you need to do. You would lose yourself without it.”

“This grind is never-ending.”

Rebekah Saltsman

To understand the market’s shape, Simon Carless, founder of GameDiscoverCo, recently calculated the gross revenue of Steam’s new releases in 2024. According to his estimates:

- The 25th-ranked game grossed roughly $33.5 million.

- The 50th grossed $12.2 million.

- The 100th grossed $5 million.

- The 250th grossed $1.43 million.

- The 500th grossed $457,000.

- The 1,000th grossed $118,000.

The long tail continues until you get to the 2,500th game, which earned an estimated $11,000. If this seems a low ranking, recall it’s 2,500th out of roughly 19,000 — placing it in the top 13% of Steam earners for that year. Even for a small studio with just a handful of employees, $11,000 won’t cover costs.

“It is a constant stress because people’s lives and homes are reliant upon you making sure the studio and projects are funded,” Rebekah Saltsman, CEO and co-founder of Finji, told Freethink.

“This grind is never-ending, and we spend a lot of time identifying the best possible thing to do with our resources that will both be the most fun and have the most impact,” she continued. “It is very stressful to chip away at studio goals like ‘drive wishlists,’ ‘increase engagement,’ ‘pitch stories for the press,’ and so on. All of this requires an enormous amount of work.”

“It is likely that someone else is working on a game very similar to yours, so yours will need to be the best it can be.”

John Baez

To keep the shingle hung, many indie studios seek out multiple sources of revenue beyond selling games. The Behemoth sells merchandise online and at trade shows, a revenue stream important enough for the team to maintain a “resident plushsmith” on staff. Others, like Finji, play dual roles as a developer and publisher.

Speaking of, a cottage industry of publishers specializing in working with indie studios, such as Finji and Playism, has also arisen in recent years. These publishers offer funding assistance, quality assurance, partnership negotiation, and marketing and public relations services. They also help with language localization, something that games have historically struggled to get right.

“When I first started, there weren’t many companies or translators offering localization services for indie games,” said Mizutani. “It was evident because I used to play a lot of indie games by overseas developers, and a lot of them had terrible Japanese localization, but nowadays, most indie games that support Japanese have decent localizations.”

For some indie studios, these publishers are a godsend — knowing that the indie scene celebrates originality and creativity, they tend to favor more of a hands-off approach than other publishers, and they free the developer to focus on what they love: designing video games.

However, for other studios, the idea of tying oneself to an outside organization defeats the purpose of working independently in the first place.

Whether an indie developer chooses to face these challenges with or without a publisher, though, one thing is for sure, according to Baez: “‘Good enough’ usually isn’t, especially these days when the barrier to entry is lower than it has ever been. It is likely that someone else is working on a game very similar to yours, so yours will need to be the best it can be.”

Game on

Laid out like that, the challenges indie studios are facing right now reflect those of the mainstream. They’re dealing with the same economic headwinds and the same struggle for player attention. Some will have to shutter their doors after disappointing sales.

For commentators like Parkin, this means that, while indie games have been a bastion of invention and creativity, they alone aren’t enough to turn the tide of hardship the gaming industry endured in 2024.

“For the health and survival of the industry built on imagination and invention, the most moneyed publishers, as leaders within the field, must take an enlightened lead and invest in projects that prioritize creativity and long-term cultural value as much as shareholder value,” he wrote in his NYT op-ed.

He’s correct, but his conclusion also misses a vital point. While no individual indie developer has the leverage of an EA or Sony, the indie scene as a whole is now a bellwether for the gaming industry.

Indie developers can keep niche genres alive long after AAA studios have abandoned them.

Because of the astronomical price tags of AAA games, big publishers are more risk averse than ever and seem content to tread in the safety of the creative shallows (with notable exceptions like Nintendo and Team Asobi). Meanwhile, indie developers have used their sleeker budgets and nimbleness to sail ahead and chart the paths that others later follow.

For instance, Fortnite (2017) is a hugely popular battle royale that earns billions in revenue for its developer Epic Games. However, the battle royale genre began as a series of user-generated mods for Arma 2 (2009), Minecraft (2011), and other games.

And speaking of Minecraft, it was developed by indie studio Mojang Studios — after the title’s popularity soared, Microsoft purchased the studio for $2.5 billion in 2014. Along with other indie darlings, such as Terraria (2011), Minecraft created the modern survival sandbox genre.

Indie developers can also keep niche genres and artistic styles alive for fans long after AAA studios have abandoned them due to a lack of broad appeal.

Nonlinear platformers, such as Nintendo’s Metroid series, were popular in the 1980s and ‘90s, but largely abandoned by the mainstream by the early 2000s. However, indie developers continued to innovate in the genre with titles like Guacamelee! (2013), Axiom Verge (2015), and Hollow Knight (2017). This reinvigorated player interest, and games in this genre are now selling better than ever.

“If you make a good game, the players will find it.”

Hiroyuki Kobayashi

The indie scene’s value to the industry runs much deeper than charting popular trends, though. It has afforded a generation of talented, creative people the freedom to make the games they want by defining success how they want.

Many of the indie developers I spoke with for this article started their careers at large studios where they were members of massive teams structured within rigid hierarchies. They said this limited their ability to pursue interesting ideas, but now that they work in smaller teams, they’re able to enjoy greater control over their work and see the impact of their ideas on the final game. Such psychological ownership has been shown to boost motivation, engagement, and work outcomes.

“The appeal is you have more control over what you do,” Adam Saltsman told Freethink. “You’re often not just working on solving problems in your game or designing a cool level or programming a cool mechanic. You’re also thinking about and actively deciding ‘Is this a good idea?’ or ‘Is this worth it?’ and then doing something about it.”

Studer and Colborn admit that their company’s game Barony isn’t for everyone. The voxelated first-person roguelike adventure co-op game is so niche that all of those words are needed to succinctly describe it — and even then, you have to know what they mean in context. Still, the studio has found a passionate community of players who enjoy and support their ideas. Thanks to that support, Turning Wheel has been able to build on Barony for years and is currently planning its next game.

Similarly, Binary Haze’s Kobayashi noted how he had previously worked for studios where leadership wanted to chase what was popular, which, in Japan, meant bright, colorful anime-style games. He decided to pursue his own vision, and the result of his and his team’s efforts was Ender Lilies, a game set in a dark, rain-soaked medieval dystopia. Like Barony, it has found a community of fans who cherish it.

“If you make a good game, the players will find it — they’ll share it with others, and the media will pick it up, too,” Kobayashi told Freethink. “That’s something that we were really honored about that happened with Ender Lilies. It’s a great situation at the moment for indies, and you just really have to take advantage of that.”

Granted, as Rebekah Saltsman noted earlier, staying in business is the priority. Still, for indie developers in the land beyond investor expectations and Metacritic scores, success can include reaching new audiences, learning new skills, expanding a genre, or simply finishing a passion project.

“What’s considered success can vary greatly from one developer to another,” said Mizutani. “Selling a certain number of units is the most common measure, but some developers are simply happy to complete and release their game.”

“I consider it a success if the developer starts creating their next indie game,” he continued. “As an avid gamer myself, it’s also my earnest wish for talented developers to continue making games.”

With the tools and technologies necessary to design games more widespread than ever, almost anyone can make a game if they love the medium and have a desire to experiment or express themselves. And if the tools and tech don’t exist, they can even make what they need themselves. They just need to start.

“Making games doesn’t have to be a big complicated job with lots of unique opportunities and challenges and publishing deals and whatever!” said Adam Saltsman. “It can also just be something that you do with your friends in your spare time to make each other laugh or get inspired or prove a point or fail gloriously or accidentally popularize a forgotten genre.”

“Some of the best games of all time were made by so-called unprofessionals, hobbyists, or modders, and making games is fun,” he continued. “I hope that folks keep getting to do it and sticking with it as much as they can!”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].