When based on a solid foundation of high quality, replicable data, a consensus statement among scholars who study a field can be powerful.

Likely the most well-known in recent decades have been the consensus studies on global warming. These show that perhaps 97% of climate scientists agree global warming is caused by human action, and they are often cited by politicians in their calls for climate action.

Argument from consensus is a well-known logical fallacy, though — a lot of people believing something doesn’t automatically make it true — and most scientific consensus claims have been proven wrong. Until the mid-19th century, for instance, it was the consensus of medical professionals that handwashing by surgeons was not necessary.

Even the global warming claim is not without contention — perhaps skeptical scholars are just edged out of publishing due to publication bias.

So, does consensus even matter?

My argument here is not against human-caused global warming (I suspect that it’s real but have no expertise), but rather to question the value and, indeed, intent of consensus statements. Their main objective appears to be to reduce doubt, allowing public policy to move forward without further debate. Yet, debate is central to science, and consensus statements may stifle scientific inquiry, given the obvious professional and social costs of questioning a consensus statement.

Indeed, I worry that, global warming aside, consensus statement efforts most often come from a position of scientific weakness rather than strength. That is to say, they too often appear to be a deliberate effort to quash debate in favor of accepting one side of a contentious issue — most often one with a moral cause pushing for more stringent government intervention.

Consensus statements on media’s effects on mental health

Attempts to communicate some kind of academic consensus on media effects began largely in the 1970s as concerns about television violence grew. Such efforts were typically led by the US surgeon general or professional guilds, such as the American Psychological Association.

Analyses of such statements have generally found them to have distorted evidence, typically claiming it was more consistent, stronger, and higher quality than it actually was. This may be due to the function of guilds, which is to promote the profession, as well as political pressure on political functionaries, such as the surgeon general.

Attempts by individual scholars themselves often appear to reflect a frustration when a consensus isn’t forming. For instance, a 2003 paper by eight prominent media violence researchers explicitly expressed dissatisfaction with a Department of Health and Human Services review of youth violence that downplayed media violence as a contributing factor.

The paper was, in part, an attempt to “set the record straight,” arguing that the authors’ view of media effects should be the default view — in the language of their essay, no scientific doubt about such effects is permitted. In another essay, published in 2009, some of these same scholars argue that “the vast majority of social scientists working in the area now accept that media violence poses a danger to society” and cast any doubt as irrational or conspiratorial.

By the 2010s, however, more disagreement had emerged between scholars on various media effects issues. This seemed to increase the number of false consensus statements.

For instance, several video game scholars conducted a survey of researchers in 2014 that they claimed indicated a broad consensus that video game violence caused societal aggression. This was immediately criticized by other scholars, in no small part because the survey data itself actually indicated a lack of consensus.

Further studies also indicated that scholarly opinion on the topic was not only mixed, but could be predicted based on age, familiarity with video games, and attitudes toward youths. Scholars who were older, didn’t play video games, and had more negative attitudes toward youths tended to worry about violent video game effects more.

Proponents of a “consensus” will use it to bully skeptics, arguing that they are irrational “denialists.”

By the late 2010s, the issue had shifted to video game “addiction.” In 2014, a group of 14 scholars claimed an “international consensus” on the topic of video game addiction: it existed and was bad. Immediately, a group of 28 scholars responded that no such consensus existed and that the original group of 14 had simply excluded anyone who might disagree with them.

The debate over video game “addiction” continues to the present day, with large groups of scholars on both sides, often with varied and conflicting opinions (i.e., some scholars worry about video game addiction, but also about moral panics about video game addiction). To date, no consensus has emerged.

These issues seem to set up a pattern: A concern about media emerges. Evidence to support the concern is inconclusive. Scholars who support the concern appear to try to circumvent the data by forcing a consensus, typically by excluding more skeptical scholars from the process. Concerned scholars then try to bully skeptics with the “consensus,” arguing they shouldn’t be listened to or are irrational “denialists.”

In 2015, I compiled examples of bullying statements by scholars attempting to force a consensus. As I noted in that study, a group of scholars from the University of New Mexico School of Medicine said of more skeptical researchers:

Despite thousands of research studies on media effects, many people simply refuse to believe them. Some academics may contribute to this because they like to “buck the establishment,” which is an easy way to promote themselves and their research. Of course, many people still believe that President Obama wasn’t born in the United States, President Kennedy wasn’t assassinated, men didn’t walk on the moon, and the Holocaust didn’t occur.

Another statement, made by Craig A. Anderson, former president of the International Society for Research on Aggression, in 2013, said, “…I hope that the [American Psychological Association] Task Force … successfully distinguish between the true experts and the industry apologists who have garnered a lot of attention with faulty methods and claims.”

Yet another statement, this one made by researchers Rowell Huesmann and Leonard Eron, critiqued a specific scholar (a public link for this article appears to have been removed):

It is also clear that Mr. [Richard] Rhodes is not an unbiased observer. He has a conflict of interest when he writes on violence. Not only is his own ego wrapped up in the view that he has been damaged by being abused as a child, but his own financial wellbeing depends on the sales of his book, “Why They Kill,” which takes the viewpoint that media violence is unimportant and being violently abused is important.

It is remarkable to read these statements from media researchers who are ostensibly concerned about youth aggression as they are remarkably aggressive. But I believe aggression underlies most consensus statements.

A new “consensus” with the same problems

While issues around video games and television have receded in the public consciousness, a new concern has emerged: Today, scholars furiously debate the potential impact of social media on youth mental health.

In Fall 2024, Italian researcher Valerio Capraro led an attempt to see if there was a consensus on social media effects by inviting scholars who’d been involved in social media research to answer a series of questions on youth mental health and social media/smartphones. (Full disclosure: I was invited to participate, but dropped out after the surveys as I felt the process had been biased.)

These questions were based on Jonathan Haidt’s book “The Anxious Generation,” which has become (in)famous for stoking fears about modern technology. Haidt’s name and that of Jean Twenge, author of “iGen,” a book on the dangers of smartphones and social media for youth, were listed as part of the coordinating team on the recruitment emails.

Given their books, both Haidt and Twenge have potential financial conflicts of interest in the study, and this likely biased response rates. I had people tell me they did not participate because they did not trust the objectivity of the team or dropped out due to low faith in the process.

Although they started the process with a list of about 250 experts, the final list of participants included just over 100. (It’s worth noting that I also heard from some people who are scholars in the field that they never actually received an invitation.)

Capraro’s team shared their paper as a preprint (meaning it hadn’t been peer-reviewed), claiming in the abstract a fair amount of consensus on multiple issues related to youth and social media.

One of the organizers of the paper, Jay van Bavel, claimed on Bluesky that journalists listening to any scholar outside this “consensus” was tantamount to “platforming a climate denialist when 97% or [sic] climate scientists agree on the state of the science.” He later deleted the post and claimed it was a joke.

In May 2025, Haidt published a newsletter arguing that the paper proved a consensus consistent with his best-selling book and that policymakers should lower the standards of evidence required to enact anti-technology policies. Many scholars speculated that being able to write this post was likely the purpose of creating the paper in the first place — or at least a predictable use of it.

“As the draft started to come together, it became more clear to me that there was a specific agenda in mind for this piece…”

Rachel Kowert

The paper created a firestorm.

The abstract and title seemed to exude an aura of consensus that, as psychologist Ruben Arslan outlined in an exhaustive series of posts and reanalyses, was not really supported by the study’s own mixed data. Many scholars reported feeling that they had been deliberately excluded from participating, while others confirmed that they had chosen not to participate due to the perceived biases of the organizing team.

The paper ironically made clear the lack of consensus in the field, not only with the tsunami of responses it triggered among scholars who weren’t involved, but also with the responses of some of the paper’s own authors, who publicly questioned the framing and reliability of the study.

I asked several of the paper’s authors about their experience participating in its creation, and their responses varied. (Note that these four are people I know and respect, and I don’t claim they represent all of the paper’s authors. The quotes below are also compiled from longer answers they sent in response to a series of questions.)

Rachel Kowert, who has done considerable research on media, told me:

As the draft started to come together, it became more clear to me that there was a specific agenda in mind for this piece that was not made clear to the contributors from the outset. For example, throughout several stages in the process I strongly suggested that they include information that screens can be used for play and other positive outcomes, but this was never incorporated.

In the end, some of the language did get tampered down, but I was disappointed in the disproportionate focus on demonstrating “ill effects” rather than balancing with positive outcomes (which, in my view, is a stronger position with greater scientific evidence behind it) in the final product. …

Many researchers dropped out during the process — I myself almost dropped out several times both from the sheer magnitude of the process (it took a lot of time) but also dissatisfaction with the direction the work was going. While I do think the first author did try to earnestly address people’s qualms (mine included), I think that the hyper focus on “proving” Haidt’s claims, rather than exploring the breadth of our understanding on this area of research, made this process flawed from the start.

I asked media psychologist Pamela Rutledge about an earlier draft of the paper’s abstract, which happened to have been forwarded to me. That draft appeared to include far more qualifiers about uncertainty in the data, but those qualifiers were removed in the posted paper:

I did see comments from Haidt in the iteration before the final version, urging a clearer statement of consensus that I did not feel the data warranted. … This was a combination of word limitations in Nature, the intended publisher, and pressure to solidify the consensus into a consensus.

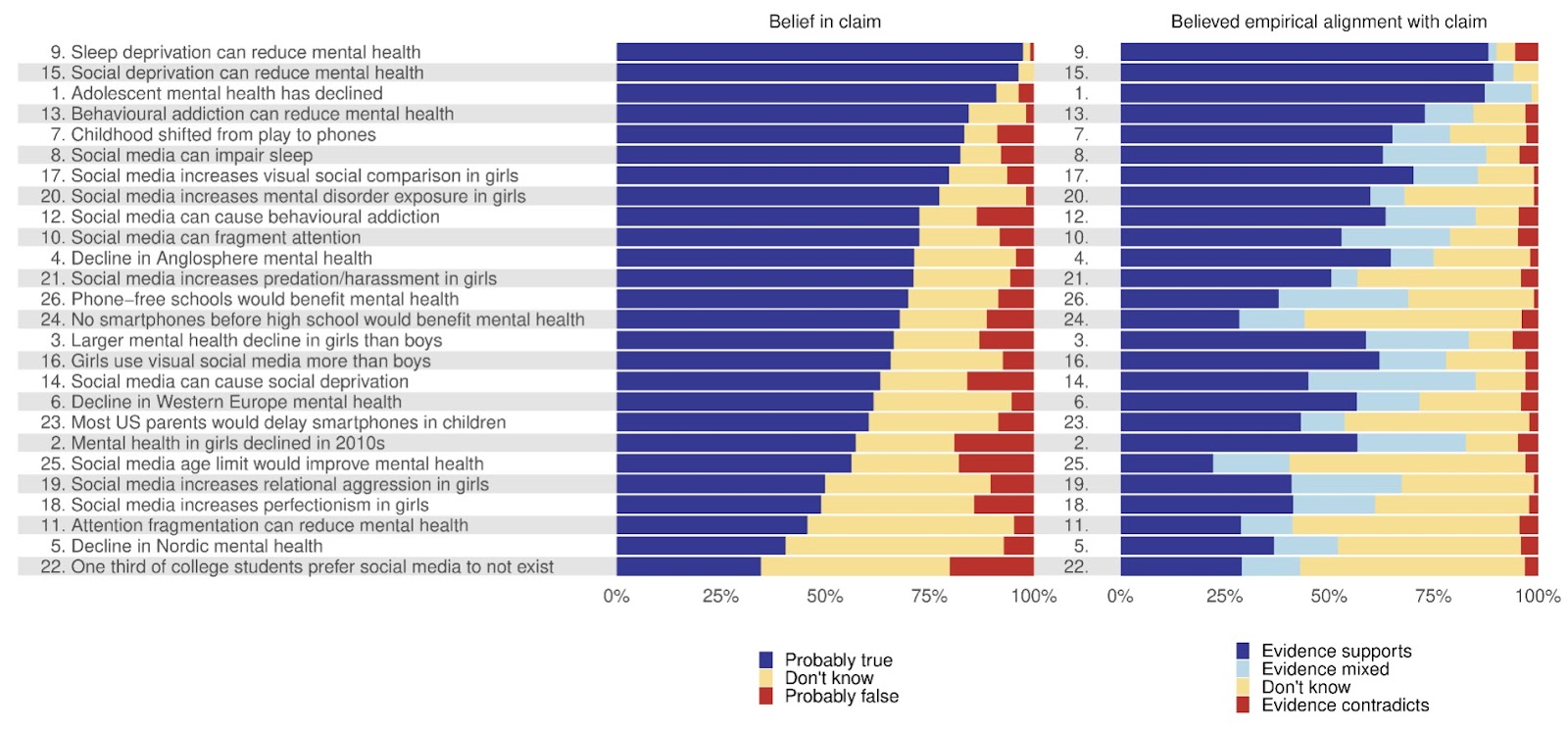

I doubt that this paper will change the minds of any participants, given that it measured beliefs. The effect of this is likely more PR than science, as it will be used to further the reductionist view of technology use and its relationship to teen mental health, which is detrimental to both issues. The irony is that this perspective will likely alienate the very young people it is intended to protect. You’ll note the wide discrepancy on the chart between beliefs about a claim versus beliefs that there is empirical support.

I asked Dylan Faulkner Selterman, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, about his experiences with the project. He emphasized positive aspects of it, believing that the organizers did listen to his voice and at least tried to get a balanced set of views, even if they ultimately failed to do so. Selterman’s concerns were mainly that a representative sample of scholars was not achieved and that the abstract failed to convey the nuances of the study:

[Lack of falsifiable claims] was a significant problem, and I pointed this out in several of my survey responses to the study team as we went through the Delphi process. The final paper does capture some of this nuance, but not enough in my opinion. For instance, one of the claims deals with something that they labeled as “behavioral addiction,” but we can’t even agree on what “behavioral addiction” actually is!

The paper reads, “Another key issue is the lack of standardized definitions and measurements for ‘social media addiction.’ Experts noted that the very definition of ‘social media addiction’ is under debate. … Yet, the lack of an agreed-upon definition complicates the interpretation of the literature and has fueled some debate over the term ‘addiction’ itself and its distinction from bad habits. Several experts argued that excessive smartphone use may be better understood as a bad habit rather than a true addiction.”

One could argue that this renders the claim unfalsifiable if we don’t have internally consistent and clear definitions for our constructs, the way we do for other psychological constructs. …

[T]hose scholars who have skeptical views on the link between digital technology and well-being were disproportionately (and conspicuously) absent from this project. That may have been by choice, and I do think the authors made an effort to include dissenting voices, but ultimately that effort was not successful. This makes it very difficult for us to establish any kind of “consensus” which is how the paper is framed.

Mark Coulson, my colleague and occasional coauthor, had perhaps the most sanguine thoughts on the consensus paper:

There was abundant evidence that throughout the process the aim of the lead authors was to listen to all voices and quantify both consensus and disagreement. The production of the MS was handled in an entirely transparent way, and all the comments I made were addressed. It felt like an extremely inclusive project, even when there were many voices that needed to be heard.

Prompted by a question regarding Jay van Bavel’s climate science comparison, Coulson responded:

The main difference as I see it here is that consensus statements about climate science arise from a pretty mature, highly rigorous, and pretty compelling position. They have the data, and the models, and it is clear what’s happening. The question is also reasonably simple — “Are human activities causing climate heating?” — to which the answer is “yes.”

The social media consensus statement is less mature, the data are less convincing, and the questions are complex. So, there are many different questions we can ask about the effects of different kinds of media and patterns of consumption, across diverse geographical areas, on different people, on different outcomes. And the data are mixed, with many of these questions not yet addressed by the kinds of high-quality randomised longitudinal studies which provide the most compelling evidence.

Of course, these are only four perspectives and hardly randomly selected, but it is interesting to see the variance in experience among coauthors on a paper about consensus. In such a context, what does “consensus” really mean?

How false consensus can shape public health narratives

One might reasonably argue that squabbles over video games or social media are low stakes, even if they are presented with a “save the children” intensity, but false claims of consensus could have serious implications for other fields, including public health.

We saw this during the early years of COVID-19, with an attempt to create “consensus” around the idea that the virus spread via Chinese wet markets rather than via a lab leak.

“There were people that did not talk about this because they feared for their careers. They feared for their grants.”

Filippa Lentzos

Whether COVID-19 had emerged naturally from transmission via animals or via escaped viral experiments from a lab in Wuhan has been an intense subject of debate.

In March 2020, a paper published in Nature claimed a natural origin for COVID-19. A letter published in the Lancet that same month would explicitly call the lab-leak explanation a conspiracy theory and imply it was racist. Signed by 27 scholars, it asserted a consensus that the lab-leak theory was false.

Emails between the authors of the Nature paper would later be used as evidence that it was designed to stifle debate over the lab leak theory. Meanwhile, reporting by journalist Paul D. Thacker would suggest that the Lancet letter was deliberately crafted to stifle scientific debate.

Ultimately, the science would change, with the lab-leak theory becoming as viable as the natural origin theory.

I’m not a medical scientist and have no real opinion on the origin of COVID-19, but what is interesting here is the attempt to cast one possible explanation as a racist conspiracy theory. It was alleged in reporting that this was done to hide an embarrassing and costly scientific mistake involving both American and Chinese researchers that cost the lives of millions.

At least some of the authors signing the Lancet letter allegedly had ties to the Wuhan lab in question, and as medical researcher Filippa Lentzos told reporters, “There were people that did not talk about this because they feared for their careers. They feared for their grants.”

As with so many other consensus statements, the authors appeared keen to cast skeptics as kooks and dangerous conspiracy theorists, even as the evidence was ambiguous.

Let the data convince, not the crowd

Perhaps trying to quantify “consensus” is the wrong approach. Such efforts are always likely to be biased by who conducts the study and who responds to it, and the very argument that a consensus exists may put social pressure on scholars to conform to it. Indeed, I submit that this has been the intent more often than not.

It may be more valuable to try to understand why scholars disagree rather than to claim they do not. When a consensus does emerge, it is more likely to do so organically and be evidenced in the absence of scholarly papers that contradict the theory under consideration. Even then, that consistency may change with new methods, new data, and new questions.

In science, the pursuit of consensus is ill-conceived. Our goal should be the pursuit of truth. The more certain we are of something, the more we should encourage others to critically evaluate our beliefs to see if they withstand rigorous testing and, indeed, skepticism. Let skeptics be convinced by good data, not social pressure.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].