It’s never been harder to trust what you see on the internet.

As artificial intelligence (AI) rapidly improves, so do the chatbots that can impersonate people online — increasingly sophisticated bots are now flooding our emails, social platforms, and even LinkedIn job postings. Suspicious text isn’t all we’re dealing with, either. AIs can also generate images, videos, and audio clips that seem like they were created by humans, but weren’t.

Tools for Humanity, a startup co-founded by theoretical physicist Alex Blania and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, is hoping to become the foundation of trust online — by verifying that the people using the internet are actually people

“The idea of a user, the idea of a person, is not really part of the internet, and that’s the core problem,” Adrian Ludwig, Tools for Humanity’s chief architect and chief information security officer, told Freethink. “In the physical world, you can tell that you’re interacting with a person, and you don’t have these problems, so we started to think about whether we could take that physical world identity and have it work in the online world.”

Look into the Orb

Tools for Humanity calls the solution it came up with the World Network, and a core element of it is a sphere-shaped device called the Orb.

People who want to become verified members of the World Network need to visit a physical location hosting an Orb so that a camera in the device can scan their eyes, a process that takes about 10 seconds. The Orb converts the texture of their irises, which is even more unique to individuals than fingerprints, into a code.

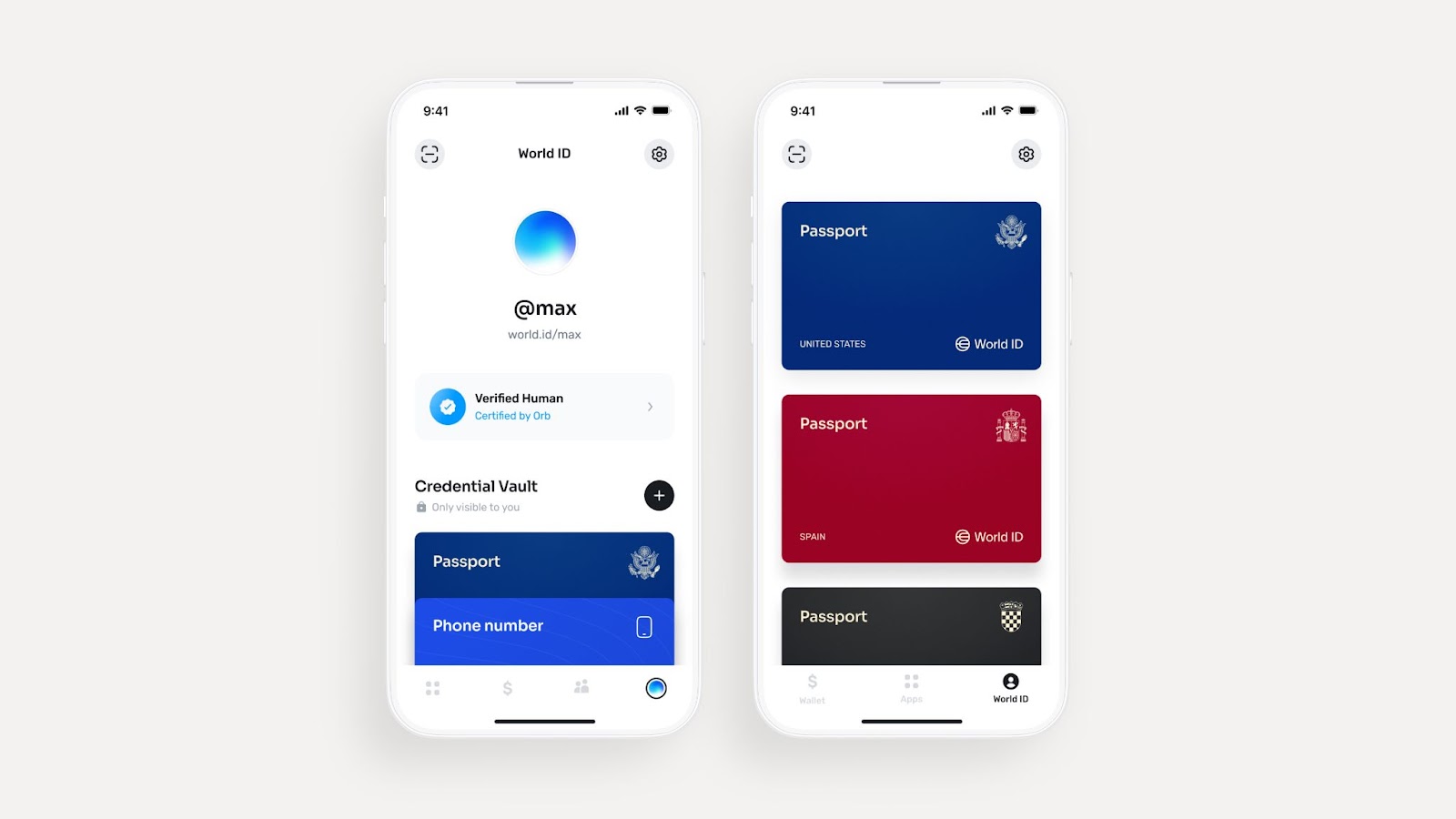

If it is a unique code — meaning one that isn’t already in the World Network — the person is issued a World ID. This proof-of-personhood is stored in the World App on their smartphone, and the idea is that it can function like a digital passport, giving them a way to prove that they are a real, unique person online without having to reveal anything specific about who they are.

“The iris can be turned into a code that reveals no other information about you other than that you’re unique, and the Orb is able to analyze that you’re human,” said Ludwig.

World IDs have myriad potential applications. A social media app could require people to share them in order to sign up, for example, ensuring that each user is a unique person. A website selling concert tickets could do the same thing, preventing bots from buying up all the good seats seconds after they’re available.

The rollout

Early testing of the Orb began in 2021, with a more official rollout beginning in 2023. Tools for Humanity has now launched the World Network in 23 countries, including the US — since April, Americans have had the option of having their personhood verified by Orbs in six US cities.

I recently visited the San Francisco location, where I chatted with employee Marlon Gomez in the middle of a wooden structure containing eight Orbs.

“As the technology develops, this is going to become more and more of a useful and necessary tool to distinguish us from computers, bots, scammers, and instances of fraud,” said Gomez. “I think the usability and necessity of this machine will continue to go up.”

“A little bit of skepticism is healthy.”

Marlon Gomez

Eventually, I walked up to one of the machines to get a closer look. At first glance, the Orb resembled a bigger, nicer version of a Logitech camera, similar to ones we had sitting on top of our computers in the early 2000s.

As I was checking out the Orbs, several bystanders walked into the store to ask about how the whole thing works. Many of them ultimately decided against it and walked out. It’s clear people are hesitant about the Orb, and I don’t blame them — “verifying your humanness” does sound rather freaky.

“A little bit of skepticism is healthy,” Gomez said, shrugging it off. “We’re just trying to educate the public and give them the confidence to research it themselves. We’re a completely open source project.”

Building trust

To have any hope of significantly reducing fraud and restoring trust online, Tools for Humanity will need a lot of people to overcome any initial skepticism they might have about the World Network.

“This technology, as well as many other technologies, only really matters and only really is powerful if it gets to wide adoption, if a lot of people actually use it,” Blania said during a keynote discussion at the IAPP’s Global Privacy Summit in April.

To encourage trust in its network, Ludwig told Freethink that the images captured by an Orb are instantly deleted and user data is never saved. A person’s World ID is only accessible on their own smartphone, and Tools for Humanity can’t access any information regarding the sites where it’s used to verify personhood.

Those sites, meanwhile, don’t get any information on the World ID user other than the fact that they are a verified human.

“We really do believe, in a pretty strong way, that the use of World ID reduces the privacy risk because you don’t need to have every single site retaining as much information as they’ve had to retain in order to fight the problem,” said Ludwig. “It’s actually less information.”

“It’s certainly been confusing for regulators.”

Adrian Ludwig

Creating the Orb in-house — rather than relying on an existing device — was also partially a trust-building move, according to Ludwig: “To be able to meet the uniqueness requirements, the security, and the privacy requirements, the only solution possible was to build our own hardware.”

And in case that’s not enough to encourage adoption, Tools for Humanity also gives people who join the World Network the option of claiming 40 tokens of its Worldcoin cryptocurrency (a total value of about $46 at the time of writing).

This token is central to the company’s plan to make World a new kind of financial network in addition to a system for verifying identity. As part of that, it recently announced a strategic partnership with Visa to release the World Card — a debit card that allows holders to spend their crypto anywhere Visa is accepted.

In addition to enticing individuals to participate in the World Network, Tools for Humanity also needs to convince government officials that it’s trustworthy. Since launching the project, it has faced ongoing pushback from regulators in certain nations, and Hong Kong has even banned the technology, citing privacy and data security concerns.

“It’s certainly been confusing for regulators,” Ludwig said. “There’s a belief that we must be retaining the images because they haven’t read the information.”

“I think a lot of it comes down to people becoming more familiar,” he added. “Just getting to the point where they realize, ‘This is a problem…that I encounter day in and day out,’ helps them feel more comfortable with the idea that they need to do something to solve the issue, and then having people be more comfortable with the solution.”

Looking ahead

As of May, 27 million people had signed up for the World Network online, and more than 12 million had been verified as humans by Orbs. To help scale up verification, Tools for Humanity recently unveiled the Orb Mini, a portable version of the Orb that looks like a smartphone.

The company’s goal is to deploy 7,500 Orbs across the US and verify 50 million people around the world by the end of this year. Helping it reach that goal will be the $135 million it recently raised from venture capital firms Andreessen Horowitz and Bain Capital Crypto.

In addition to increasing the size of the World Network itself, Tools for Humanity is also working to grow the number of organizations accepting World IDs as proof of personhood, as well as identify— over the past few months, it has partnered with Match Group and Razer to help verify people on the dating and gaming platforms, respectively.

“One really interesting feature that’s relevant for Tinder is called Deep Face,” said Ludwig. “The Orb takes a picture of your face and that is encrypted and signed, so you know it’s an image that was captured by a secure camera.”

“Later, you can have a challenge where you say, ‘Is the person that I’m interacting with online the same as the person that went to an Orb?’” he continued. “You could do a private check where you prove that the images this person is posting are the same.”

Eventually, World IDs could do more than give people the ability to verify that they are humans — once we get to the point that we’re comfortable allowing AIs to take action for us, they could also be linked to our AI agents.

“What does it mean to have a bot taking an action on my behalf and how can I do that in a trustworthy way? How can I know that it is a bot that’s acting on behalf of Adrian to perform a task that Adrian has said it’s okay for that bot to do?” said Ludwig.

“That kind of delegation is something that doesn’t exist right now,” he continued, “but it’s at the edge of the types of challenges that we imagine on the internet in the not too distant future.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].