Concern about deceptively edited photos feels like a very modern anxiety, yet a century ago similar worries were being litigated.

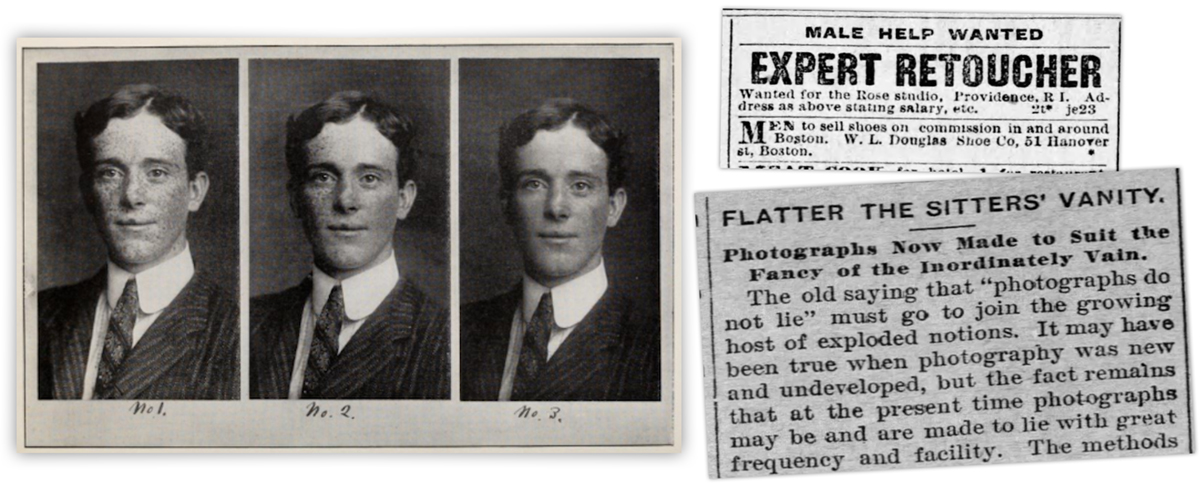

Portrait photography gave rise to an industry of photo retouching — analog “beauty filters” — to flatter subjects in a way portrait painters once did. This trend led to questions about technology distorting our perceptions of beauty, reality, and truth.

An 1897 issue of the New-York Tribune would declare the assumption “Photographs Do Not Lie” an “exploded notion,” saying that “…at the present time photographs may be and are made to lie with great frequency and facility.”

Other commercial applications of photo retouching emerged. In 1911, tourists visiting Washington DC could acquire fake photographs of themselves posing with then-President of the United States William Taft. This troubled government officials. Upon discovering the practice in 1911, a US attorney ordered it stopped.

One (literal) photo-shop offering the novel souvenirs appealed to the White House for its blessing to continue the trade, but was denied. (The practice was not against the law, but pressure from the White House appeared effective, if only temporarily, in the capital.)

Photographic crimes

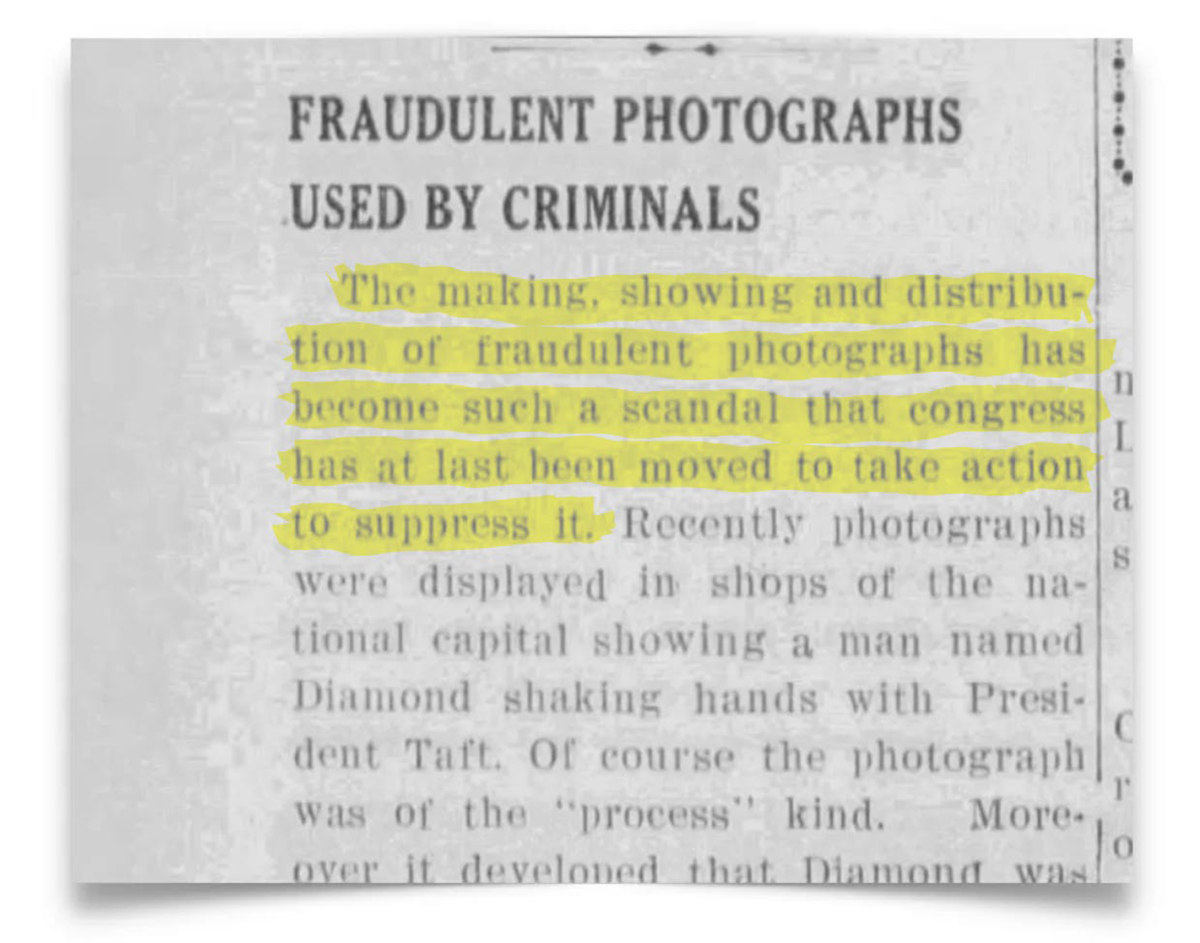

The following year, a fugitive wanted for people trafficking was found in possession of a fake photo posing with President Taft. It was reported he’d used it to buy the trust of his victims.

That this seemingly benign practice had been weaponized prompted some to demand it be regulated against abuse. The Justice Department prepared a law that was introduced by then-Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who’d similarly been troubled after reportedly finding a photograph of himself with someone he’d never met.

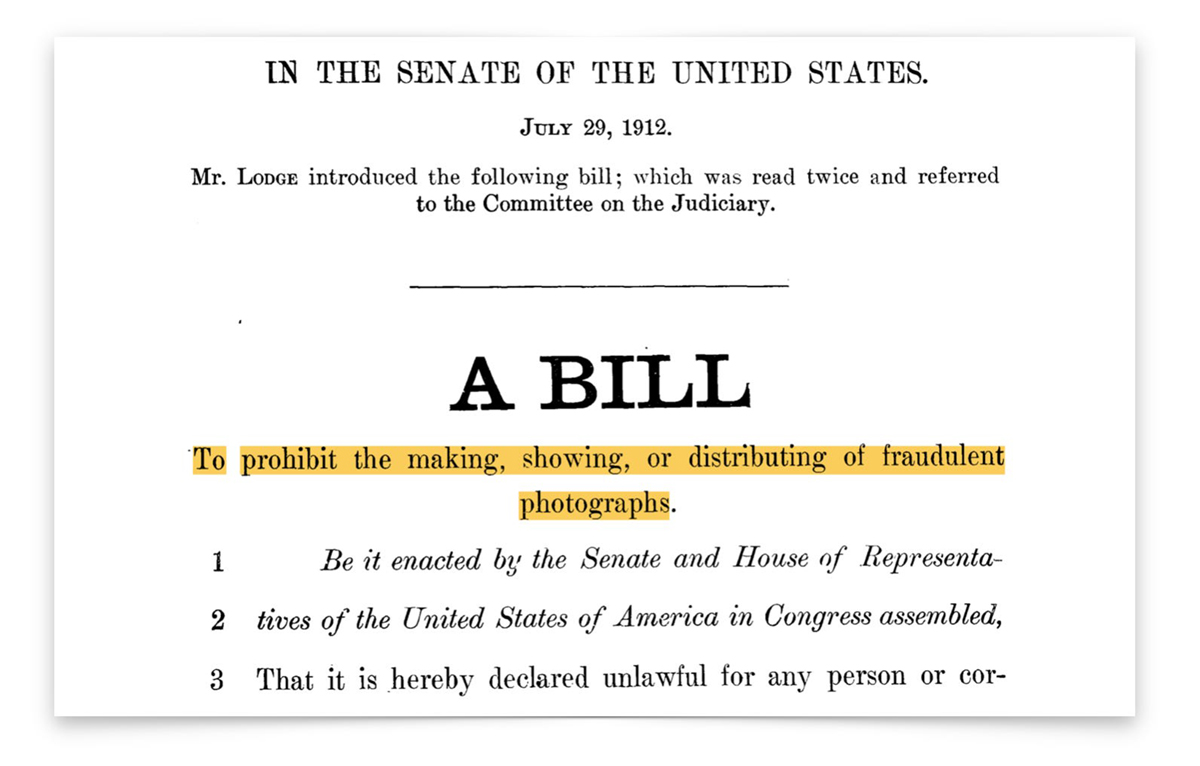

On July 29, 1912, the bill was introduced to the Senate “to prohibit the making, showing, or distributing of fraudulent photographs.”

The law would make it illegal “to make, sell, publish, or show” any “fraudulent or untrue photograph, or picture purporting to be a photograph” of anyone who had not first given permission. Violation would see punishment of up to six months in jail or a fine up to $1,000 (~$31,800 adjusted for inflation).

The proposed rules made headlines across the US, bringing the topic of fake photographs to wider attention.

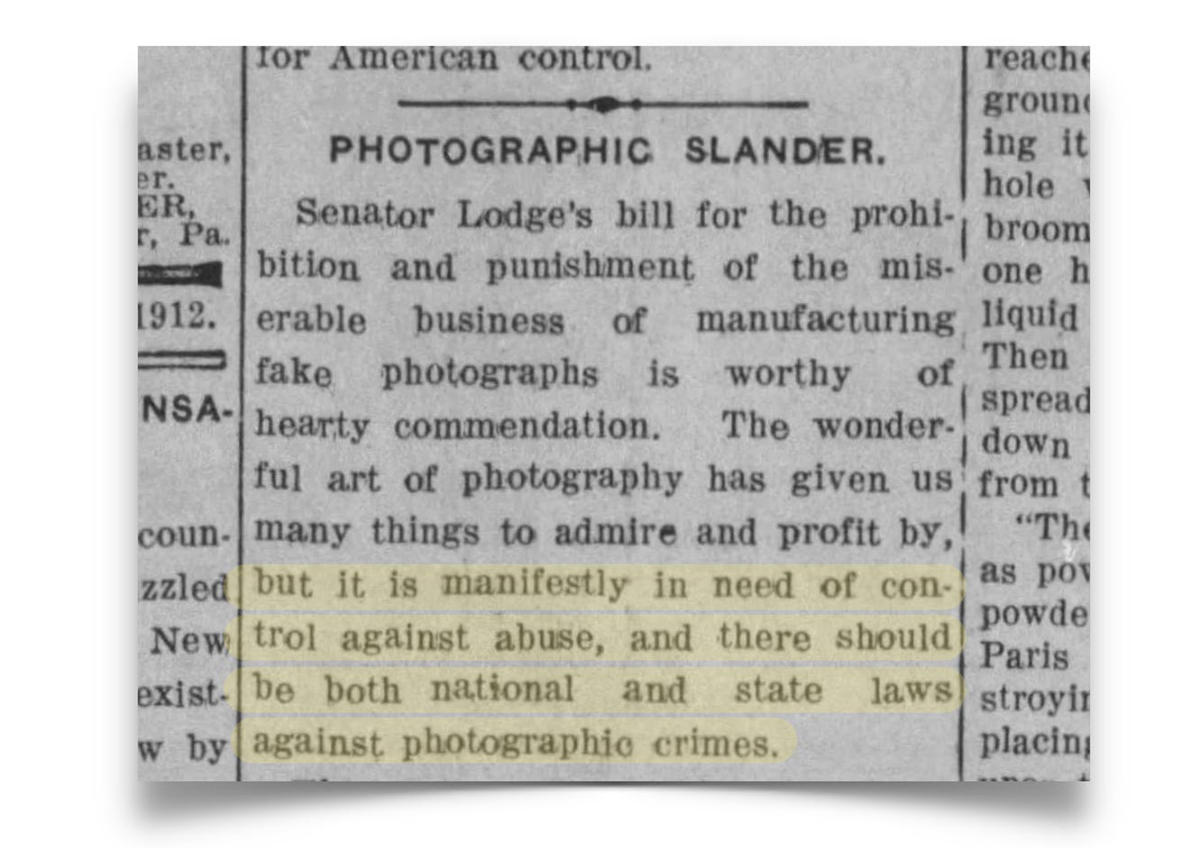

The Intelligencer Journal of Pennsylvania applauded Senator Lodge’s efforts to combat the “miserable business of creating fake photographs,” saying that while the technology of photography was a “wonderful art,” it was “manifestly in need of control against abuse.”

The piece emphasized the need for “national and state laws” to address negatives “artfully combined to tell pictorial lies” something the author called “photographic crimes,” warning that anyone was now vulnerable to slander from fake photos “apparently faithful and exhibited as the testimony of the innocent sun.”

Not everyone was a fan of the proposed law, however — some representing the photography community worried about the bills’ unintended consequences. A 1912 edition of the publication “American Photography” called it “indefensible,” saying that the law would make photographers and publishers “continually liable to blackmailing suits” — we assume by those claiming to have never given permission.

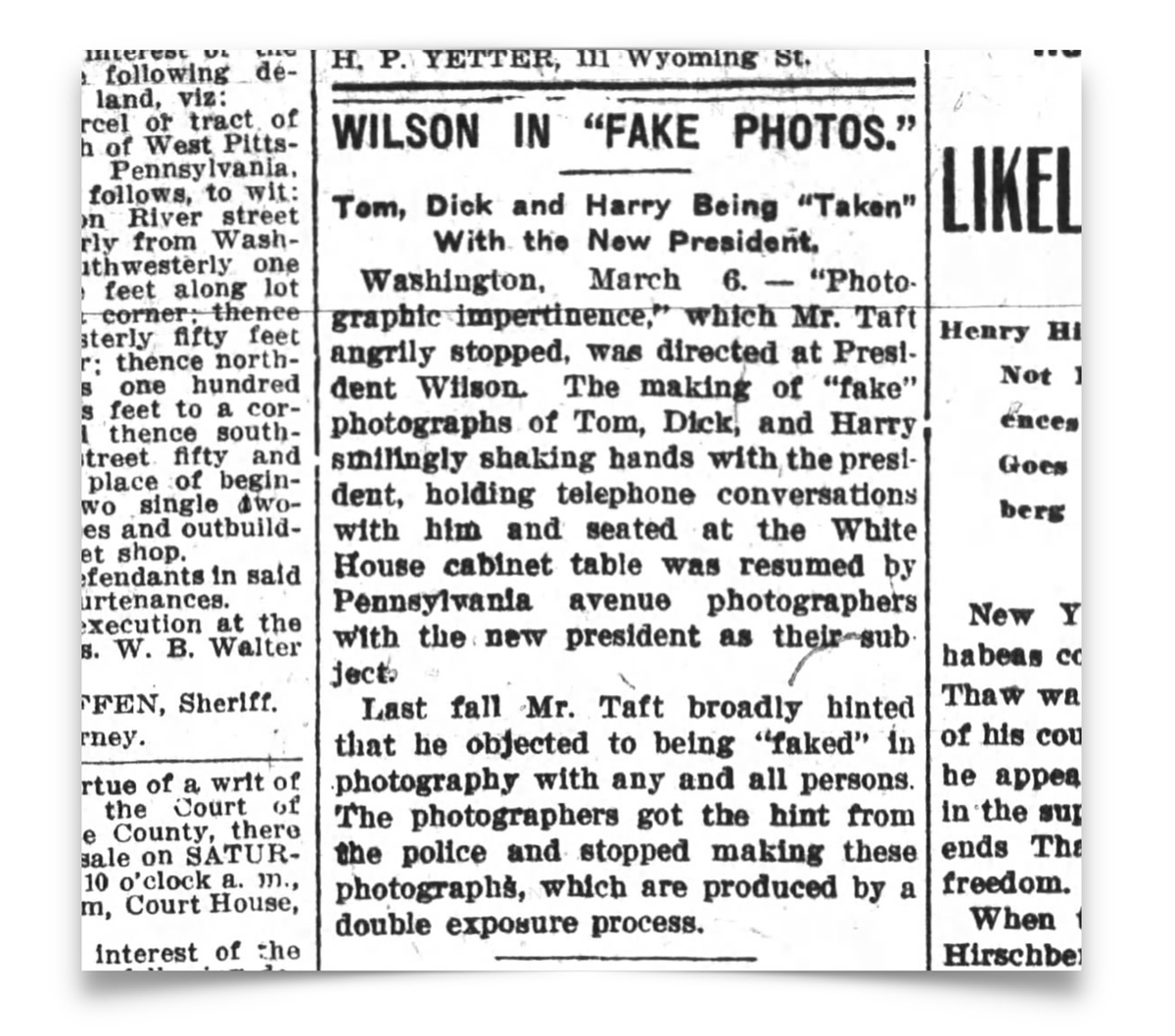

It appears the bill was never voted on and died in the Senate. The following year, President Taft would lose an election to Woodrow Wilson, and reports of a renewed trade in fake photos of President Wilson in the Capital would soon appear.

What if…

Had the law passed, it would have been very relevant in the 21st century, with the rise of digital photography, Photoshop, and, more recently, AI-enabled image editing.

It would have made a federal crime of removing an object from a photo for Instagram without permission of everyone in it. On the other hand, recent efforts to legislate against fake nude images would be unneeded — those would be illegal already.

Surprisingly, this latter issue was also present in prior centuries.

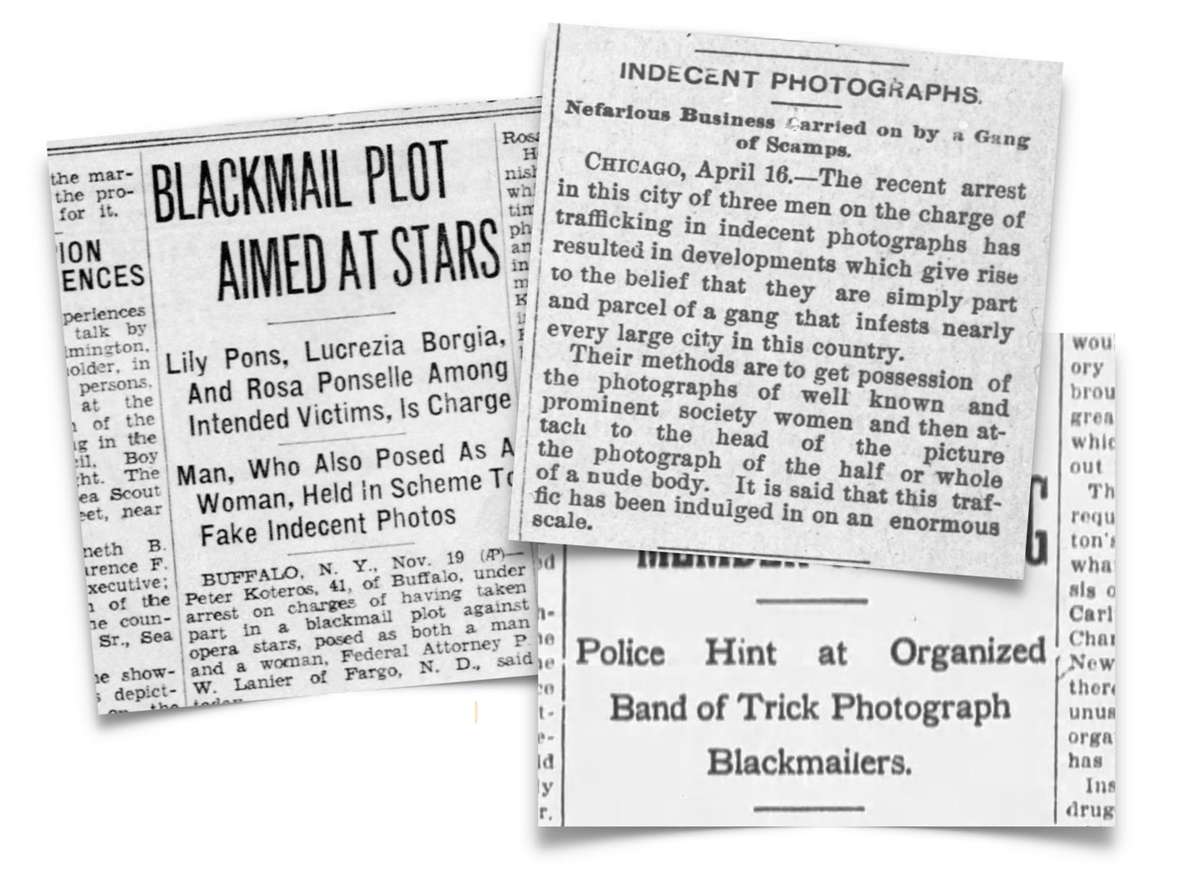

Unmentioned in defense of the proposed law were real cases of “photographic slander” against women. In 1905, a gang was using the threat of “the circulation of indecent trick photographs for the purposes of blackmail.” A 1891 report out of Chicago noted the arrest of a “gang of scamps” selling fake nude images of high society women, and 1936 would see a blackmail plot against opera stars.

Fake nudes could have been banned over a century ago, but the law was too broad, focusing on more speculative harms rather than specific proven ones. A similar critique is made of some AI regulation proposed today, potentially making this a good lesson for the best way to approach AI regulation.

Side note: hypocrisy

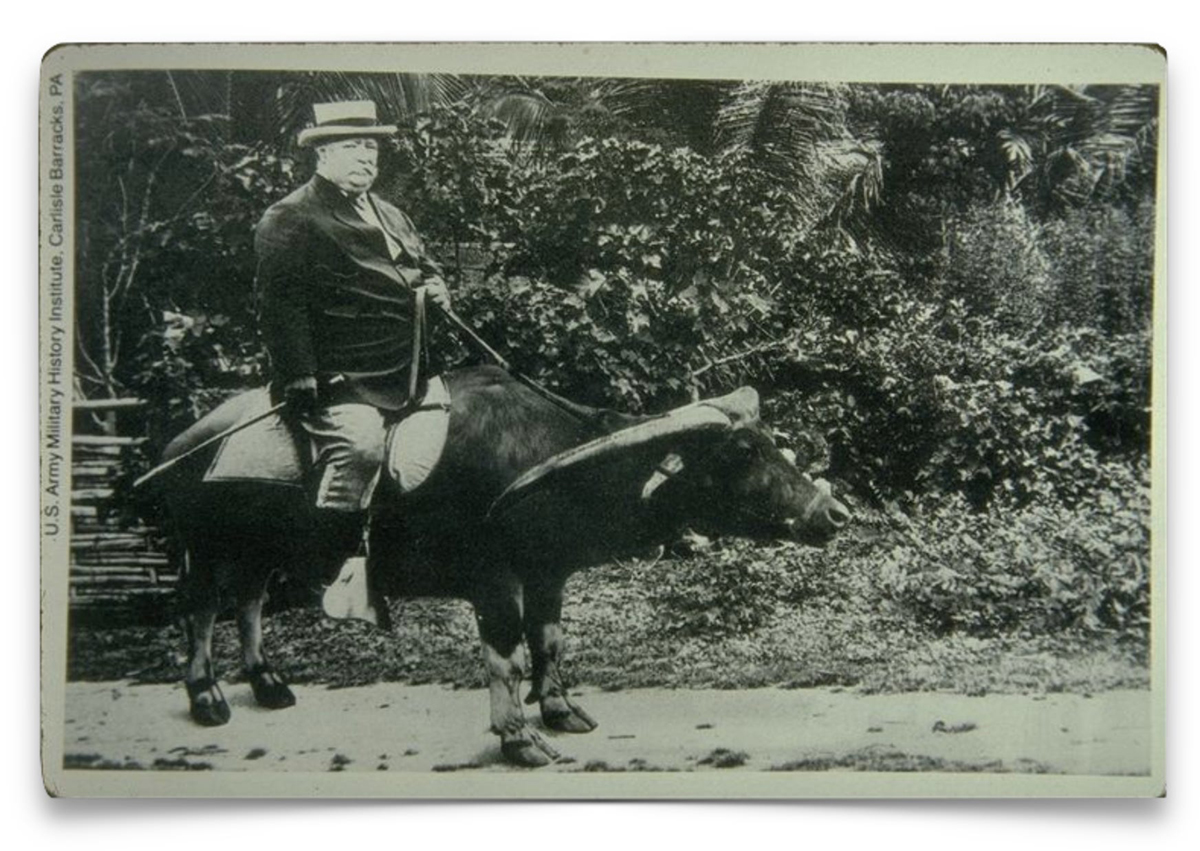

In 1923, a year after the law was proposed, a photo would appear of President Taft atop a Carabao, the national animal of the Philippines. It was thought to have been part of an effort to buy goodwill with a nation seeking independence from the United States.

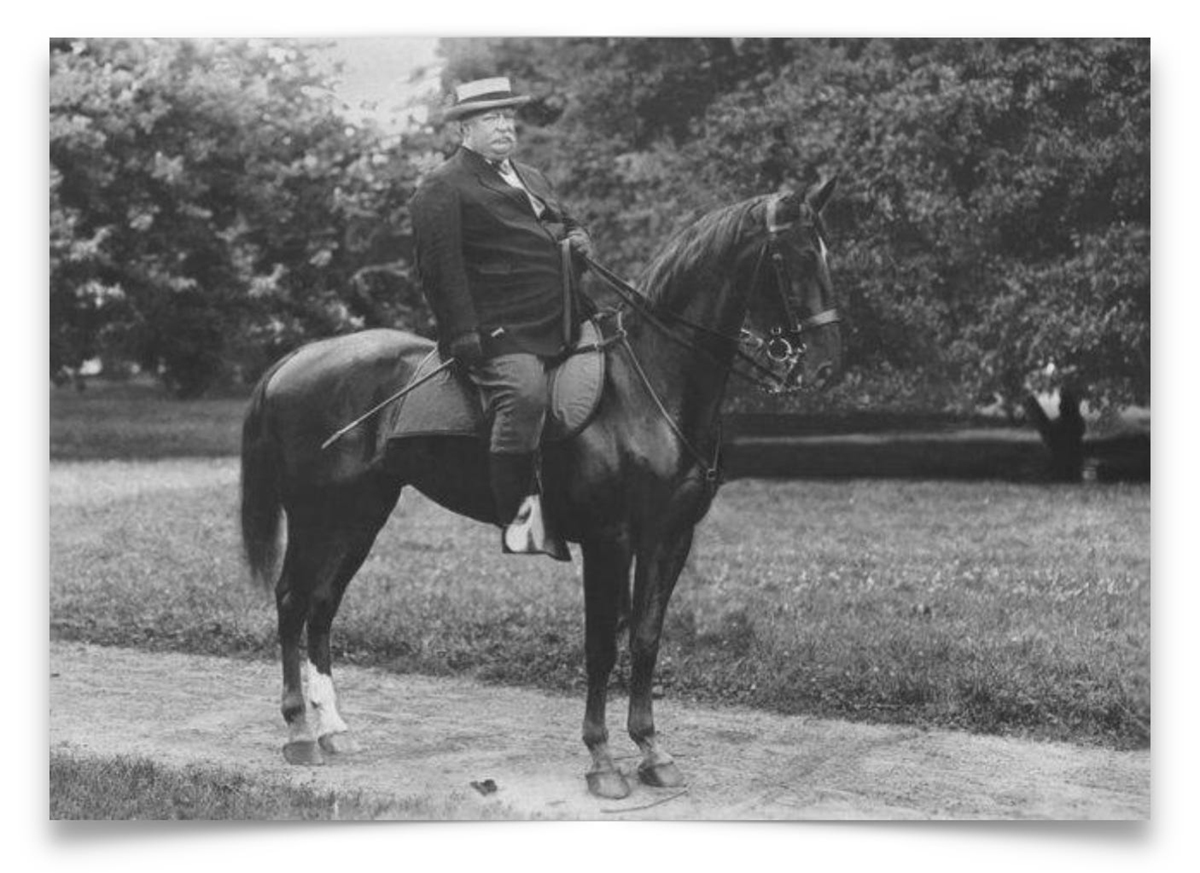

It turns out, it was the very kind of fake photo the Taft administration was railing against. In 2018, history researcher Bob Couttie discovered a 1908 photo of President Taft astride a horse in an identical pose: comparing the images, it seems undeniable that Taft had been cut and pasted onto a different image — literally.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].