California is reconsidering a plan to shutter its last nuclear power plant in 2025, joining Japan, Germany, and other nations in reexamining nuclear’s role in our clean energy future.

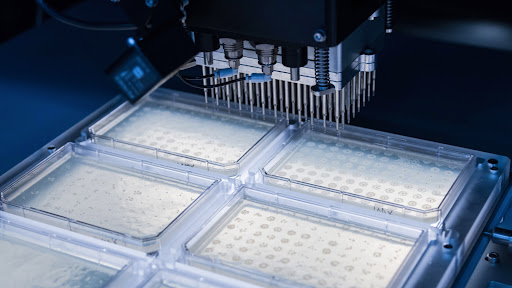

Nuclear power: When atoms are split, they release a tremendous amount of energy in the form of heat. That process is nuclear fission, and we can use the heat to boil water, creating steam to spin electric turbines.

A nuclear power plant doesn’t generate greenhouse gas emissions, making the energy source cleaner than coal or natural gas. Nuclear plants also take up much less space than solar and wind farms and are more consistent than those renewables, whose output varies based on the season and time of day.

California’s last nuclear power plant is scheduled to close in 2025.

The challenge: Today, approximately 440 nuclear power reactors are generating 10% of the world’s total electricity and 28% of its low-carbon power — but the energy source is on the decline, with more than 70 reactors shutting down since 2000.

The closures are typically financially motivated — electricity from renewables and natural gas is getting cheaper, and the aging plants are due for potentially costly upgrades and licensing renewals — or spurred by pressure from a public worried about meltdowns and radioactive waste.

Staying alive: California’s Diablo Canyon Power Plant is one of the next on the chopping block — in 2016, its operator, Pacific Gas & Electric Co. (PG&E), announced plans to close the plant when its licenses expire in 2025 rather than pay for needed environmental and safety upgrades.

California’s plan was to replace the plant’s capacity with renewables, but it doesn’t look like the state will be able to scale up its solar and wind farms fast enough, meaning it’ll have to lean more heavily on natural gas plants and importing power from out of state.

“The state is focused on maintaining energy reliability while accelerating efforts to combat climate change.”

Newsom administration spokesperson

To avoid that scenario, Governor Gavin Newsom’s administration has drafted a bill that would delay Diablo Canyon’s decommissioning until at least 2030 — by loaning PG&E up to $1.4 billion to help pay the cost of upgrades and licensing.

“In the face of extreme heat, wildfires, and other extreme events that strain our current electrical system, the state is focused on maintaining energy reliability while accelerating efforts to combat climate change,” said a spokesperson from Newsom’s office.

“[T]he Governor supports keeping all options on the table as we build out our plan to ensure reliable energy this summer and beyond,” they added.

Power trend: California isn’t alone in seeing the benefits of maintaining nuclear plants, either.

In November 2021, the US approved $6 billion in funding for nuclear power plants set to close prematurely due to financial issues, and concerns about grid stability and conflicts with Russia have Germany reconsidering plans to shutter its last three nuclear power plants at the end of 2022.

Japan, meanwhile, is restarting several aging nuclear reactors that had been shut down after Fukushima to help stabilize its grid and fight rising electricity prices.

“The risks of falling short of our climate goals exceed the risks of including nuclear energy as part of the zero carbon energy mix.”

Jason Bordoff

The bottom line: We know from disasters like Chernobyl and Fukushima that an accident at a nuclear power plant can be devastating, but nuclear still causes far fewer deaths than coal, gas, and oil, and we simply can’t meet our climate goals if we continue to shutter clean power plants prematurely.

While doing what we can to keep those plants operational, we need to continue ramping up other renewables and developing systems that will make new nuclear systems cheaper, safer, and cleaner, such as small modular reactors and advanced storage options for nuclear waste.

“We have to incorporate nuclear energy in a way that acknowledges it’s not risk-free,” Jason Bordoff, co-founding dean of the Columbia Climate School, told NPR in January 2022. “But the risks of falling short of our climate goals exceed the risks of including nuclear energy as part of the zero carbon energy mix.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].