In an effort to stem Brazil’s epidemic of dengue fever, the World Mosquito Project has announced an ambitious plan: a massive mosquito factory that would be capable of cranking out 5 billion specially-modified bloodsuckers every year.

While it sounds a bit counterintuitive to fight mosquito-borne viruses with more mosquitoes, it’s actually part of a disease control strategy which has shown huge promise.

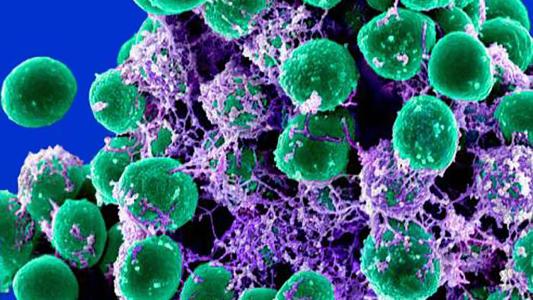

These mosquitoes, purposefully infected with a common (and harmless) bacteria called Wolbachia, become much less likely to transmit other infections, because the bacteria outcompetes them inside the mosquito. Wolbachia then tips the reproductive scales so that more eggs hatch carrying the bacteria, spreading it throughout the population.

“This will be the biggest facility in the world” producing Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, Scott O’Neill, a microbiologist and head of the World Mosquito Project, told Nature’s Mariana Lenharo.

“And it will allow us in a short period of time to cover more people than in any other country.”

To fight dengue virus, Brazil wants to release billions more mosquitoes.

Public enemy No. 1: Besides being annoying, mosquitoes carry a plethora of nasty pathogens, killing hundreds of thousands of people per year with malaria and dengue — which the WHO estimates causes 40,000 deaths a year — alone. Hundreds of millions of others are sickened every year. Mosquitoes also spread yellow, chikungunya, and Rift Valley fevers, and West Nile and Zika viruses.

As is common with infectious disease, the burden lies heaviest on the developing world, especially children.

Although it had been dengue-free for decades, the virus re-emerged in Brazil in 1981. Now, the nation can clock over a million infections per year — and cases are not only exploding but also expanding in area, putting ever more people at risk. Dengue has also proven difficult to make a vaccine for.

A little help: Wolbachia bacteria may help curb the spread of mosquito-borne diseases.

The bacteria specializes in infecting insects, and it’s got pretty broad taste — an estimated 6 in 10 of all types of insects harbor it. After a team at Brazil’s University of São Paulo discovered that the bacteria protected fruit flies from infection with RNA viruses in 2008, further research revealed that it could also stymie multiple mosquito viruses — including Zika, yellow fever, chikungunya, and dengue.

It does so by beating the viruses at their own game. Wolbachia outcompetes viruses in the same biological niches they need in the mosquito, making it hard for them to replicate; and the less the viruses are replicating, the lower the odds a mosquito spreads them.

The technique has been tested a few times, including in Brazil, and one extensive trial in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, provided very strong evidence that it works.

In their trial, the researchers split the city into 24 zones, with eggs of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes randomly placed in half of them. The Wolbachia zones had a 77% reduction in cases and an 86% reduction in hospitalizations from dengue, compared to the untreated zones.

Brazil’s mosquito factory: As Nature’s Lenharo pointed out, those excellent numbers don’t hold across the board, but instead vary with location. In Brazil, tests in the southeastern city of Niterói led to a 69% decrease in dengue cases, but across Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro, there was only a 38% reduction.

The differences may partly be due to environmental differences — for example, in places with bigger native mosquito populations, it may take longer for Wolbachia to take hold. Societal issues can hamper interventions as well; violence in Rio interfered with the project in some cases.

“While we’ve worked very closely with people in those communities, it can be slow work to build trust and to be able to operationalize plans,” O’Neill told Lenharo. The WMP is looking at how to automate the spread of the Wolbachia mosquitoes and various methods of doing so, including drones, cars, and motorbikes, Lenharo reported.

The mosquitoes, purposefully infected with a common (and harmless) bacteria called Wolbachia, become much less likely to transmit other infections.

Despite data suggesting it works, Wolbachia mosquitoes are not a “silver bullet,” WMP collaborator Luciano Moreira told Lenharo. “The Wolbachia method is complementary, and we should work with integrated methods to control dengue, Zika and chikungunya,” he said.

The location for the mosquito factory has yet to be determined, Lenharo reported, but WMP expects it to be operational by 2024.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].