In the fight against dengue fever, we may have a new — and powerful — ally: a bug that infects mosquitoes.

A new randomized controlled study has provided the best evidence yet that infecting mosquitoes with a bacteria, called Wolbachia pipientis, can dramatically cut down the rates of infections and hospitalizations caused by the “breakbone fever” virus.

University of Liverpool infection biologist Ewa Chrostek, who was not involved with the study, told Science that the results were a “breakthrough” that makes Wolbachia infection “much closer to … being an official strategy to control dengue.”

A nasty, tricky, and spreading foe: Dengue fever is caused by the dengue virus, transmitted to people via the bite of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Despite being widespread — and spreading — a dengue fever vaccine remains elusive; while there are pest control methods that help stop the virus’s spread by killing or repelling the mosquitoes, they simply aren’t enough.

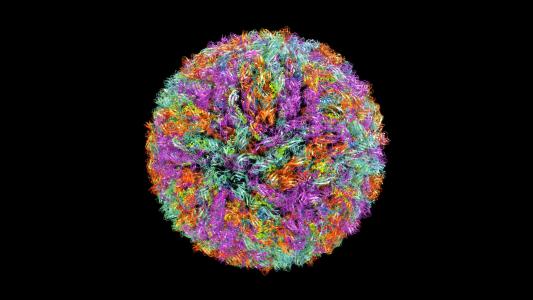

Bacteria vs. virus: Wolbachia is a bacterium that infects insects, and it’s not picky about it — roughly 6 in 10 of all types of insects harbor it. Research has revealed Wolbachia to be more than just a parasite, however; in 2008, it was shown to protect fruit flies from infection by RNA viruses. Shortly thereafter, researchers figured out that it can stymie the replication of numerous mosquito-borne viruses, including dengue, Zika, West Nile, yellow fever, and chikungunya.

Wolbachia does this by hanging out in the same places in the mosquito that the viruses do and outcompeting them, the BBC explains. This makes it hard for the virus to replicate, reducing the odds that an infected mosquito transmits the virus the next time it feeds. Best of all, the bacteria is an insect specialist and can’t infect mammals.

Release the Wolbachia: To put the bacteria to the test, researchers from the World Mosquito Program (WMP) introduced Wolbachia-infected mosquito eggs in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

The city was split into 24 zones, the BBC explains, and the bacteria-bearing eggs — five million in all — were randomly introduced to half of them. Every two weeks, researchers put the eggs into buckets of water placed in the zones; after nine months, a suitable population of Wolbachia mosquitoes was built up.

The results, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, were “better than we could have hoped for to be honest,” Katie Anders, WMP director of impact assessment, told the BBC.

After the infected mosquito population had been established, consenting patients with fevers were enrolled in a network of clinics monitored for three years. Zones seeded with Wolbachia mosquitoes had a 77% reduction in cases against all four varieties of dengue fever virus — and an 86% reduction in people needing hospital care.

“That’s really the big thing,” WMP investigator Cameron Simmons told Science. “It’s the weight of hospitalization … that really stretches health systems.”

Short-term excitement, long-term monitoring: “We are delighted with the outcome of this trial,” Yudiria Amelia, head of disease prevention in Yogyakarta, told the BBC. “We hope this method can be implemented in all areas of Yogyakarta and further expanded in all cities in Indonesia.”

Boston University professor of global health David Hamer — who wrote an editorial on the study for NEJM — told the BBC that Wolbachia infection had “exciting potential” for countering dengue and all its nasty brethren, including Zika, West Nile, and chikungunya.

“This is a great technology, but we need to think about the longer run,” Ary Hoffmann, a University of Melbourne researcher who worked on a previous Wolbachia release in Yogyakarta, told Science.

While Wolbachia levels have stayed strong for up to a decade in some areas they’ve been released, the genomes of the mosquitoes, the bacteria, or the dengue virus (and viruses just love to do this) could mutate and dampen the bacteria’s protective effect.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].