Australian researchers have developed a way to study the structure of a flavivirus, without the need for high-security biocontainment, Monash University announced.

Their technique uses a flavivirus that is harmless to vertebrates — including humans — modified to express an outer shell that looks identical to dangerous mosquito-borne viruses, like dengue.

Wearing its nasty little getup, the researchers can study the structure of flaviviruses that can infect humans, without risking infection. The incognito virus will be a huge boost to labs studying vaccines and treatments for these diseases.

Pests and pestilence: You may not recognize the word, but you’ve likely heard of a flavivirus or two. Carried by infected mosquitoes, flaviviruses include such public health menaces as dengue, Zika, and yellow fever.

Already, nearly a third of the Earth’s population is at risk of flavivirus infection, Monash points out — and there’s been an increase in cases of dengue, as well as viruses popping up in new places.

It’s a lowball, but the WHO estimates that there are around 390 million cases — and 20,000 deaths — due to dengue alone every year. And that’s just one flavivirus.

Despite their well-documented nature, there’s little we have currently to fight them, except for pest control — which works, but has its own challenges.

“With limited vaccines and no targeted therapeutics available, flaviviruses continue to pose a significant global threat to human health,” the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Nature Communications.

Knowing the structure of the viruses can help researchers identify vulnerabilities, which in turn can help them develop flavivirus antivirals and vaccines.

But mapping out the 3D shell of a virus requires specialized microscopes, and if the flavivirus in question is pathogenic — capable of causing disease in humans — you’re going to need those microscopes to be in special labs designed to contain such pathogens.

And there’s apparently not many of them.

A chimeric model: To get around this problem, the researchers turned to another Australian resident for help: Binjari virus. The Binjari virus is a flavivirus that only infects insects, making it safer to handle, and can’t be transmitted to people.

Wearing its nasty little getup, the researchers can study the structure of flaviviruses that can infect humans, without risking infection.

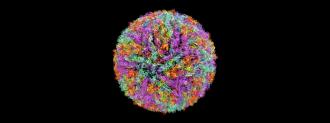

To help get a better molecular map for flaviviruses that do infect people, the teams at Monash and the University of Queensland modified the benign flavivirus so that it carries an outer shell nearly identical to medically important viruses, including dengue.

Viruses that combine genetics like this are known as chimeric viruses, in honor of the hodgepodge beast of Greek mythology.

“Because the structural proteins are derived from the human-infecting virus, the particles look like the pathogenic virus,” Watterson said.

And that means they can reveal their weaknesses.

How to kill a virus: To find out just how accurate their chimeric flaviviruses were, the researchers turned to Monash’s Ramaciotti Centre for Cryo-Electron Microscopy to analyze the chimeras.

The chimera’s shells mimicked their infectious cousins’ down to minute details, allowing the researchers to identify potential target sites in dengue virus.

“We show that these sites are essential for viral growth and important for viral maturation,” the researchers wrote in their study. “These findings define a hallmark of flavivirus virions and a potential target for broad-spectrum antivirals and vaccine design.”

The team hopes that their Binjari-based model will provide “a universal path to the safe and rapid structure determination for existing and emerging flaviviruses.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].