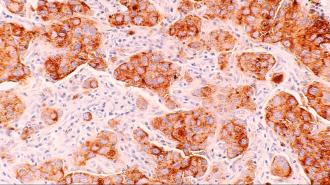

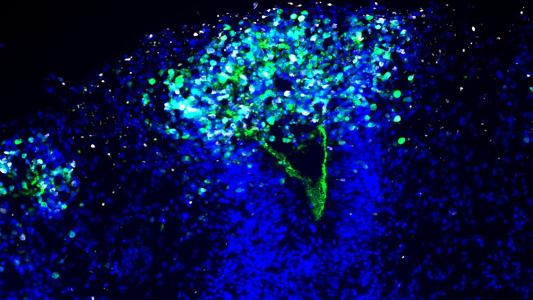

Cancer is the target of some of the most advanced treatments in medicine’s arsenal. Proton therapy bombards tumors with targeted streams of positively charged particles. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (engineered white blood cells) penetrate into tumors and destroy cancer cells. CAR T-cell therapy sends reprogrammed T-cells to hunt down out-of-control cells.

Oddly, however, clinicians often neglect a simpler way to potentially fight cancer, one that can be used in tandem with other therapies: food.

Dietary interventions for cancer were the focus of a recent review article published in the journal Trends in Molecular Medicine. The authors, Carlos Martínez-Garay and Nabil Djouder, scientists at Spain’s National Cancer Research Center, described how “precision nutrition” could maximize the effectiveness of cancer therapies with limited complications.

As Martínez-Garay and Djouder wrote, researchers have noticed for some time that cancer cells demand large amounts of glucose (sugar) and certain amino acids to fuel their rampant growth, raising the potential that diets that limit these compounds could slow cancer’s spread.

Animal studies on diet and cancer

Promising preliminary trials conducted in animals show that tumor growth can be slowed through dietary means. A nutritionally balanced, low-calorie diet has been found to lower blood glucose levels in mice, which in turn slows tumor growth and metastasis. An intermittent-fasting diet accomplishes the same. A ketogenic diet high in fat and protein but very low in carbohydrates also lowers blood glucose and hinders cancer in mice. This diet also has the added effect of increasing the amount of ketones in the body. These are energy-storing chemicals derived from the breakdown of fat. Healthy cells can efficiently process ketones to fuel their functioning, while cancer cells cannot.

Other studies have found that different types of cancer have different demands for certain amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. The same goes for lipids (fats). Thus, restricting certain amino acids and lipids in the diet could put the brakes on cancer’s growth.

Precision nutrition in humans

Unfortunately, the promising performance of precision nutrition in animals has not yet been conclusively proven in human clinical trials. But this is mostly because the few studies carried out so far have been short in duration and lacking in subjects. The dearth of solid experiments is understandable because maintaining a proper diet can be exceedingly difficult for cancer patients. Many of the available therapies have harsh side effects that reduce appetite and cause severe nausea. Doctors are often more concerned with getting their patients to eat anything at all. Implementing a specifically tailored cancer-fighting diet plan based on preliminary data — no matter how promising — is simply not a priority.

Martínez-Garay and Djouder argue that the potential of precision nutrition to fight cancer merits larger randomized controlled trials. They wrote:

“The advent of molecular oncology — the ability to analyze tumors in depth and classify them based on their molecular profile — has shifted the philosophy of treatment from generalized treatments for most cancer types towards specific approaches tailored to each cancer type and stage. This approach… can also be applied to nutrition, combining clinical data with microbiome screens, nutrigenomics, molecular diagnostics, and metabolomics to develop dietary regimes aimed at targeting specific cancer abnormalities while maintaining or improving patient metabolic health.”

Although precision nutrition has significant potential in cancer care, it is essential to stress that diet is a complementary treatment and should be used alongside conventional therapies. It is not an alternative. The cautionary tale here is that of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, who — when diagnosed with a treatable form of pancreatic cancer in 2003 — initially opted to pursue alternative medicine approaches, including a fruitarian diet rather than surgery to treat his cancer. While he did eventually elect the evidence-based surgery, his hesitancy ultimately may have led to his demise: His cancer metastasized and killed him seven years later.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.