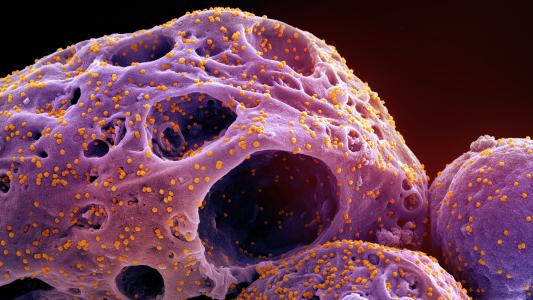

A “superbug” vaccine that temporarily puts the immune system on high alert could one day reduce the number of people who contract MRSA, pneumonia, and other infections while in the hospital.

The challenge: One out of every 31 hospital patients in the US is battling an infection they contracted while in the hospital for a different health issue. These healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) can extend a patient’s stay, increase their hospital bill, or worse — every year, more than 90,000 Americans die of an HAI.

While some HAIs respond to standard infection treatments, most are caused by pathogens that have evolved resistance to our antimicrobials, and there currently aren’t vaccines to protect people from the most common of these “superbugs.”

“Even if there were such vaccines, multiple vaccines would have to be deployed simultaneously to protect against the full slate of antibiotic-resistant microbes that cause healthcare-acquired infections,” said Brian Luna, an assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at USC.

Every year, more than 90,000 Americans die of an infection they contracted while in the hospital.

A superbug vaccine: Rather than trying to develop new treatments or vaccines targeting a host of specific pathogens, Luna and his colleagues at USC led the development of a vaccine that temporarily puts the immune system on high alert for any dangerous invaders.

The idea is that a patient would receive this superbug vaccine when they’re first admitted to the hospital, giving them extra protection against infections during their stay.

“It’s an early warning system,” said senior author Brad Spellberg. “It’s like Homeland Security putting out a terror alert. ‘Everybody, keep your eyes open. Keep an eye out for suspicious packages.”

“You’re alerting the soldiers and tanks of your immune system,” he continued. “The vaccine activates them. ‘Oh my god, there’s danger here. I better turn into the Hulk.’ I mean, when you have bad superbugs lurking, that’s when you want the Hulk waiting to pounce rather than Dr. Banner, right?”

How it works: The superbug vaccine contains three ingredients, and two are already used in FDA-approved vaccines. The third is a piece of a fungus often found on human skin — this is the antigen that triggers the immune response.

In tests on mice, the vaccine increased their supply of macrophages, a type of immune cell that eats pathogens, and it gave them protection against the bugs that cause MRSA, pneumonia, and other common HAIs. When the rodents did develop infections, their survival times were longer than unvaccinated controls.

In the animals, the vaccine started working within 24 hours and protection lasted for up to 28 days. Only 5% of hospital stays last longer than three weeks, and a second shot could potentially extend the protective window for those in the hospital for longer periods, according to the team’s testing.

“It’s like Homeland Security putting out a terror alert. ‘Everybody, keep your eyes open'”

Brad Spellberg

The limitations: The researchers note that they only tested their vaccine against these superbugs, so more studies are needed to find out whether it might be able to prevent HAIs caused by other pathogens.

This vaccine likely isn’t something that could be given to every person admitted to a hospital, either — presumably, at least some will have conditions where triggering the immune system in this way wouldn’t be recommended.

Looking ahead: The USC researchers have formed a startup, ExBaq, to continue developing their superbug vaccine and are already in talks with vaccine manufacturers, including AstraZeneca, about partnering on the project.

The next step will be a clinical trial in healthy volunteers to determine the ideal dosage and confirm that the vaccine is safe.

“[B]acteria will always find a way to outsmart the antibiotics, so I think developing a vaccine that will prevent infection from happening in the first place will be a lot more effective,” said first author Jun Yan.

“Also, by preventing the infection and reducing the amount of infections that we see in the hospital, that will also decrease the amount of antibiotics that doctors has to use, which is also a means to combat antibiotic resistance,” she added.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].