This month, Apple began delivering their amazing mixed reality headset, the Apple Vision Pro, and I am confident it will wow consumers and invigorate the industry. You might think this review would please Apple, but if I was an app developer for the Vision Pro, three words would be violating Apple’s language guidelines — I called it a mixed reality headset.

Instead, Apple calls their headset a spatial computer, a thoughtful term justified by the product’s advanced features. That said, Apple has taken their branding one step further by imposing language restrictions on app developers that have raised eyebrows: “Refer to your app as a spatial computing app. Don’t describe your app experience as augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), extended reality (XR), or mixed reality (MR).”

I appreciate the need for disciplined branding, but I worry Apple is going too far by actively working to suppress language that has a long and rich history. I say this as someone who began working in this field when the phrase virtual reality had just emerged and before augmented reality, mixed reality, or extended reality had been coined.

This means I’ve lived through the full evolution of this language over the last 30+ years, with various twists and turns. When I was a young researcher conducting VR depth-perception experiments at NASA, the photo below was a large poster in the lab where I was working. To me, it was a deeply inspiring image, capturing both the present and future of the field:

The fact is, the human experience depicted in the photo above has been called virtual reality for almost 40 years. If you are a developer for the Vision Pro and you create a fully simulated immersive experience, is it really such a problem to describe it as virtual reality? The VR headset shown above is now in the Smithsonian. This is our history and culture, and it should not be branded away.

Of course, the Vision Pro is orders of magnitude more sophisticated than the old NASA headset, not just because it’s higher fidelity but because it adds entirely new capabilities. The most significant capability is the power of the Vision Pro to seamlessly combine the real world with spatially projected virtual content to create a single unified experience — a single perceptual reality. This is called augmented reality (AR) or mixed reality (MR), depending on the capabilities, and both phrases have a long, useful history.

AR vs. MR

This is probably the most misunderstood dichotomy in the world of immersive technologies. For most of my career, only one phrase was needed — augmented reality — but its definition has been diluted over the years as marketeers pushed simpler and simpler systems to fall under the banner, confusing the public.

I began working on merging real and virtual environments in 1991, before there was language to describe such a combined experience. My focus back then was to explore the basic requirements needed to create a unified perceptual reality of the physical and virtual. (I called this “design for perception” — admittedly, not very catchy.) But I learned a lot. One thing I determined was that the real and virtual realms needed to be spatially aligned in full 3D space, with sufficient precision that the flaws are beyond the limits of human perception (called the “Just Noticeable Difference” or JND in the field of psychophysics).

Even subtle flaws destroy the illusion, and your brain perceives the real and virtual as separate, not one reality.

In addition, both realms needed to be simultaneously interactive — for example, the user needs to be able to reach out and engage naturally with both real and virtual at the same time, cementing the illusion that the virtual content is an authentic part of the physical surroundings. And finally, the real and virtual need to engage each other (bi-directionally interactive), because without that consistency the illusion is lost. If you grab a virtual book and place it on a real table, and it falls through — it’s not perceived as a unified reality and suspension of disbelief is gone.

Even subtle flaws destroy the illusion.

Because no language existed back then, I referred to merging the real and the virtual as creating “spatially registered perceptual overlays.” Also not very catchy. Fortunately, “augmented reality” was coined at Boeing soon after and quickly took off. I liked this language a lot. Augmented reality clearly describes the objective of the technology — to add virtual content to a real environment that is so naturally integrated, the two worlds merge together in your mind, becoming a single reality. And for almost 20 years, that’s what the phrase augmented reality meant (while simpler devices that merely embellished or annotated your field of view were called head-up displays).

And then, in 2013, Google Glass happened. I respect that product and believe it was ahead of its time. Unfortunately, the media incorrectly referred to it as augmented reality. It was not. It didn’t enable virtual content to be placed into the real world in a way that was immersive, spatially registered, or interactive. Instead, it was what we now call smart glasses, which are useful and will become even more useful as AI gets integrated into these products — but it wasn’t AR.

Augmented reality got further watered down during the 2010s, as smartphone apps were pushing simple visual overlays as “augmented reality,” even though they were not immersive and lacked 3D registration with the real world. They also lacked user interactivity and bi-directional interactivity between the real and virtual. Today’s phones are much better — many now have LiDAR and other scanning technologies, enabling spatial registration and interactivity — but the concept of AR got diluted.

I’m sure I wasn’t the only one frustrated by AR language being watered down. I suspect that the team at Microsoft working on the first commercial product that enabled true augmented reality (the HoloLens) were also annoyed. In fact, I speculate that this is why Microsoft, upon launching the HoloLens, focused their language on the phrase mixed reality (MR).

This phrase had been around since 1993, but it was with the HoloLens launch, which was also ahead of its time, that MR really took off. It basically came to mean genuine augmented reality.

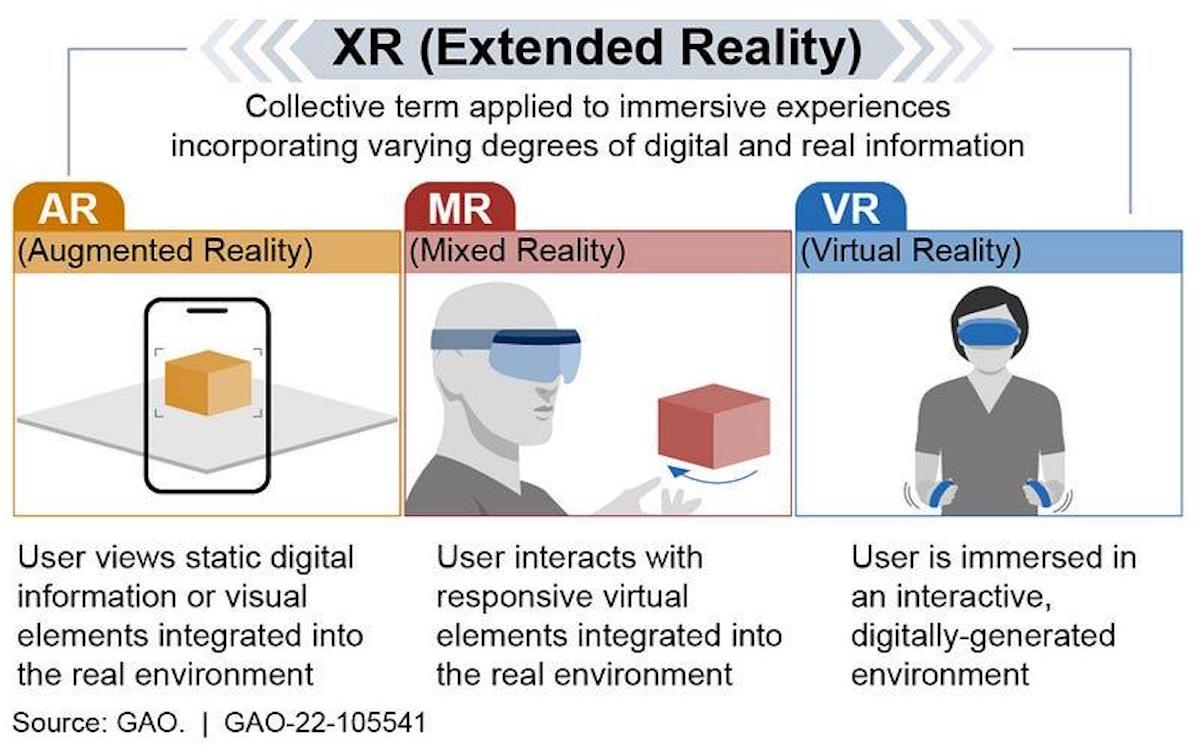

So, now we have two terms that describe different levels of augmenting a user’s surroundings with spatially registered virtual content. To help clarify the difference between AR, MR, and VR, we can look at definitions that were published in 2022 by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO). (Why the GAO cares about the differences between these phrases isn’t obvious, but I have to assume it’s to clarify whether government contracts are paying for virtual reality, augmented reality, or mixed reality devices.)

The GAO created this simple image to summarize the differences:

It’s not about screens or glasses

It’s worth noting that the difference between AR and MR now has nothing to do with the hardware and everything to do with the experience. I bring this up because many people incorrectly believe that AR hardware refers to glasses with transparent screens you can peer through, and MR hardware refers to headsets that use “passthrough cameras” to capture the real world and display it to the user on internal screens. This is not true.

I say that as someone who used passthrough cameras in the first system I built for the US Air Force back in 1992 (called the Virtual Fixtures platform). I made that design choice because it allowed me to register the 3D coordinate systems for the real and the virtual with higher precision, not because it changed the user experience. And besides, simple phone-based AR also uses cameras, so that is not the differentiator.

This leads me back to the Apple Vision Pro — it is a mixed reality headset, not because it uses passthrough cameras, but because it enables users to experience the real world merged with interactive virtual content that is spatially registered with a user’s natural surroundings with precision, creating one unified reality.

Because mixed reality is the superset technology, the Vision Pro can also provide simpler augmented reality experiences and fully simulated virtual reality experiences. And for all three (VR, AR, and MR), I expect the Vision Pro to amaze consumers with experiences that far exceed any device ever built, at any price. It’s a true achievement for Apple and the team of engineers who made it happen.

The Vision Pro also enables other capabilities that are entirely unique, including a spatial operating system (visionOS) that breaks exciting new ground by using a user’s gaze direction for input. So, the Vision Pro is not only a mixed reality headset, but also a spatial computer and frankly, a work of art. I also believe that spatial computing is a great overarching term for AR, MR, and VR experiences and adds some new twists that relate to spatial operating systems — all to the good.

My recommendation is that Apple not be too heavy handed in suppressing the historic and accepted language of the field. I am old enough to remember Apple’s biggest product launch, the famous “1984” Super Bowl ad that unveiled the Mac. It featured a runner throwing a massive hammer to shatter an Orwellian screen where Big Brother controls society by replacing common language with “newspeak.” In that same spirit, I hope Apple will allow developers to reference VR, AR, and MR experiences on the Vision Pro by name. After all, we want an immersive future where 2+2 still equals 4.

Louis Rosenberg, PhD is a pioneer in the fields of virtual and augmented reality and a longtime AI researcher. He founded Immersion Corporation (IMMR: Nasdaq) in 1993 and Unanimous AI in 2014, and for developing the first mixed reality system at the Air Force Research Laboratory. His new book, Our Next Reality, is available for preorder from Hachette.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].