On June 17, 2024, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy published an op-ed in The New York Times advocating for a “warning label on social media platforms” to address possible risks to adolescent mental health. Despite the nation’s top doctor suggesting harm, the causative effects of social media on teen mental health are still uncertain — the science is not in.

This isn’t the first time a surgeon general jumped the gun in response to concerns about technology and children.

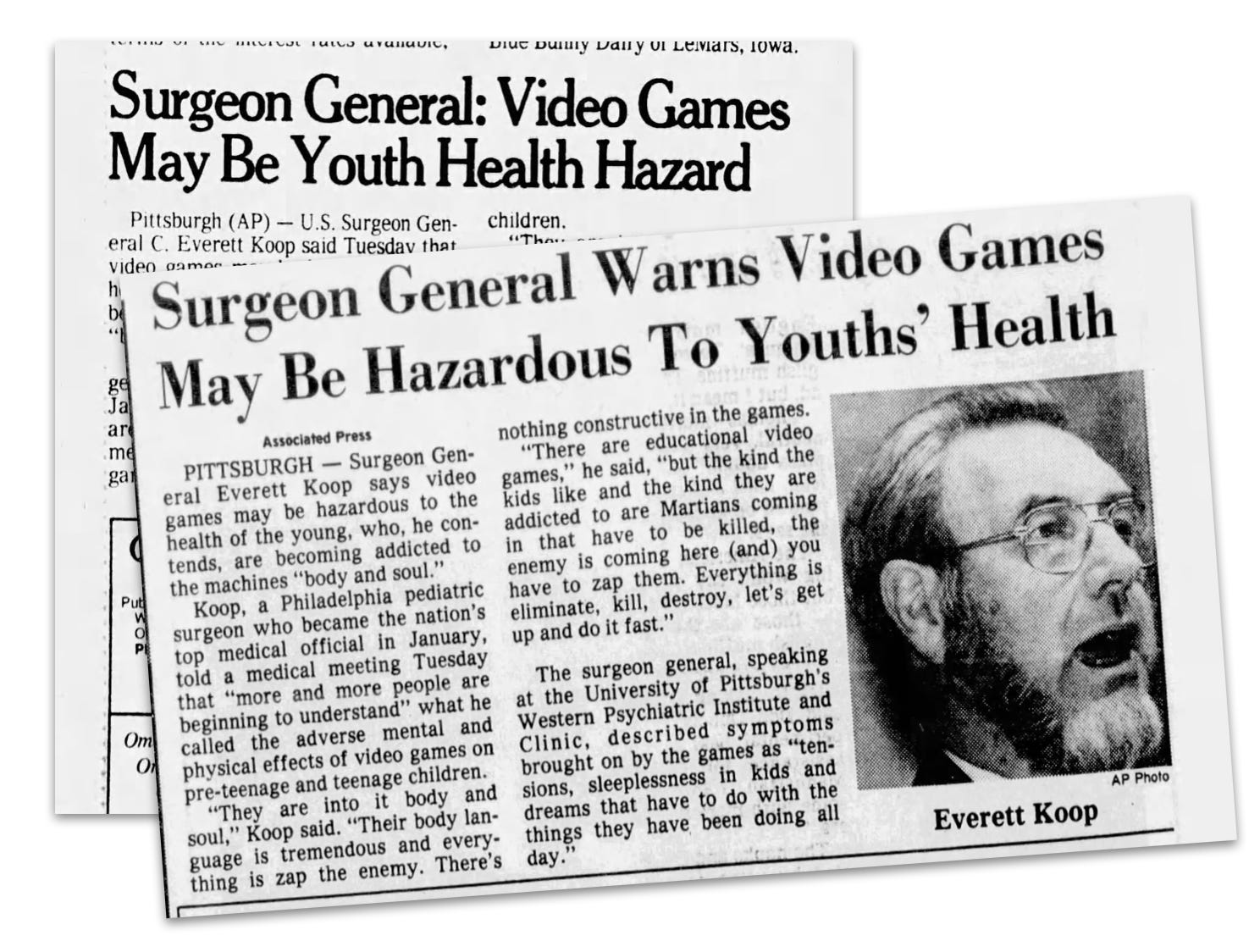

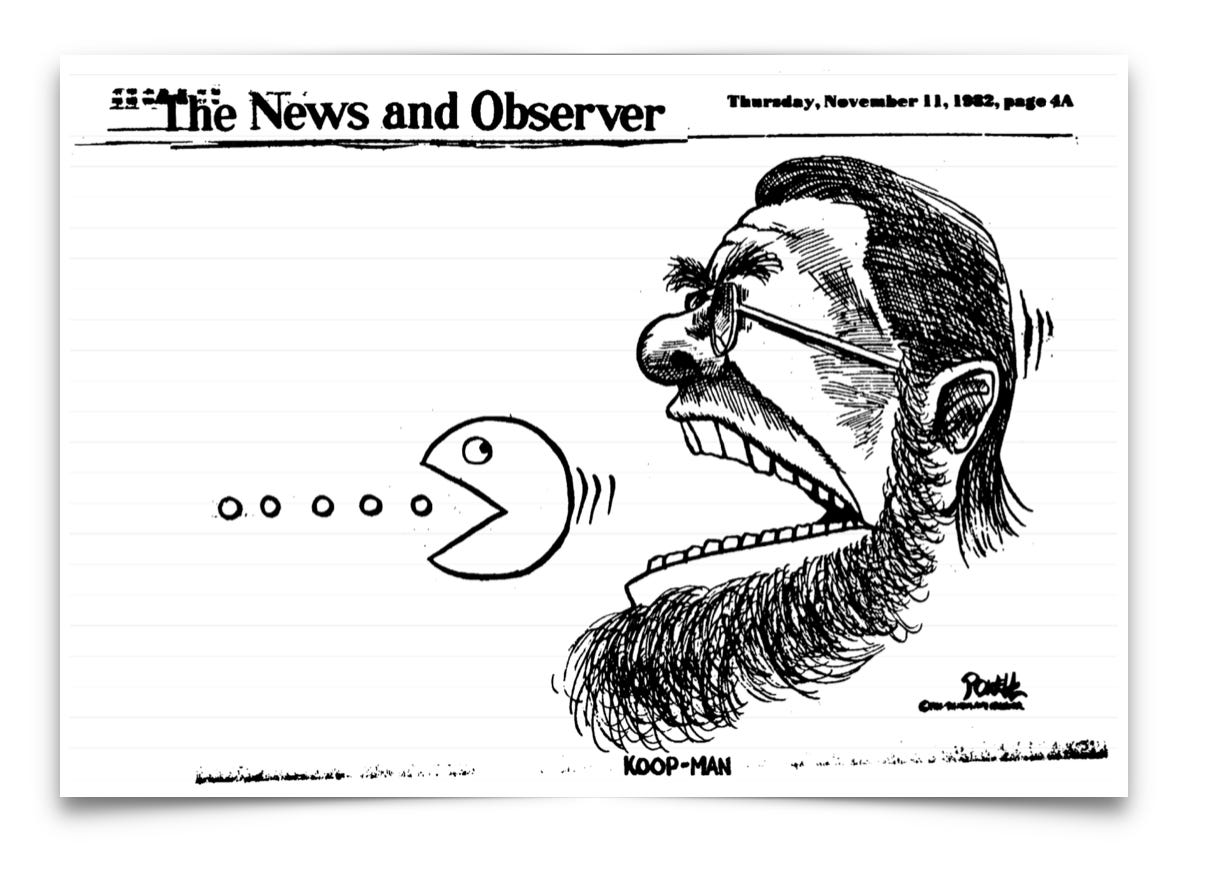

In November 1982, then-Surgeon General Everett Koop would sound a warning about the risks of video games to youth and resulting “aberrations in childhood behavior.” He would note the risks weren’t proven, but ensured scientific proof would inevitably emerge.

“Dr. Koop said he had no scientific evidence on the effect of video games on children, but he predicted statistical evidence would be forthcoming soon from the health care fields,” wrote the Associated Press.

Pac-Man panic

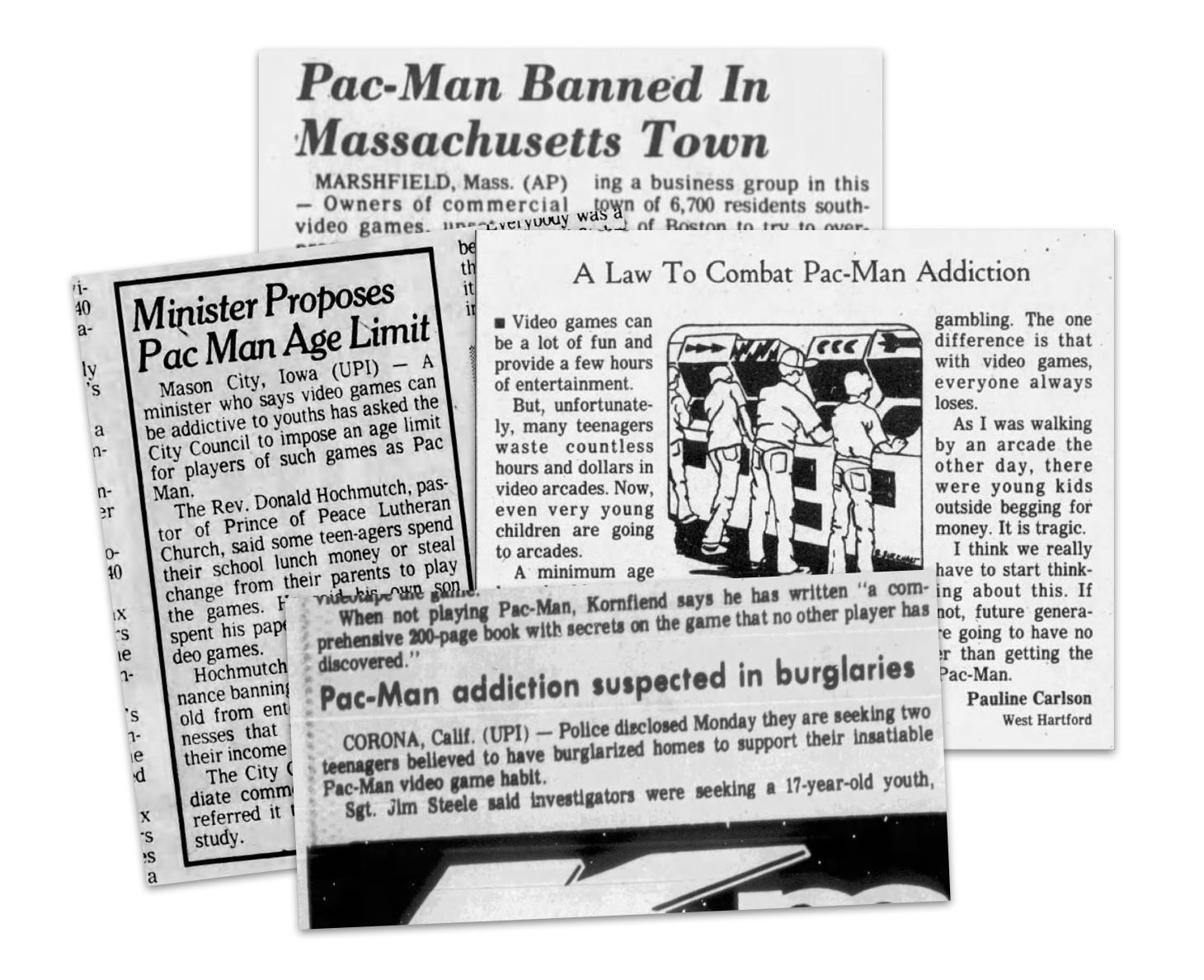

The surgeon general’s comments came amidst a boom in arcade machines and the first of many panics about video games. Children would swarm the machines, feeding them coins obtained from parents, sometimes covertly. Where comic books and television were blamed for corrupting the youth in prior decades, video games were the new boogeyman. The surgeon general’s comments only added fuel to the fire.

Age limit laws would be proposed, one police department blamed burglaries on the rapacious demand for quarters, and one Massachusetts town even outlawed the commercialization of arcade machines. Koop’s implication that his opinions would soon be proven scientific fact were quickly denounced by psychologists and the burgeoning video game industry.

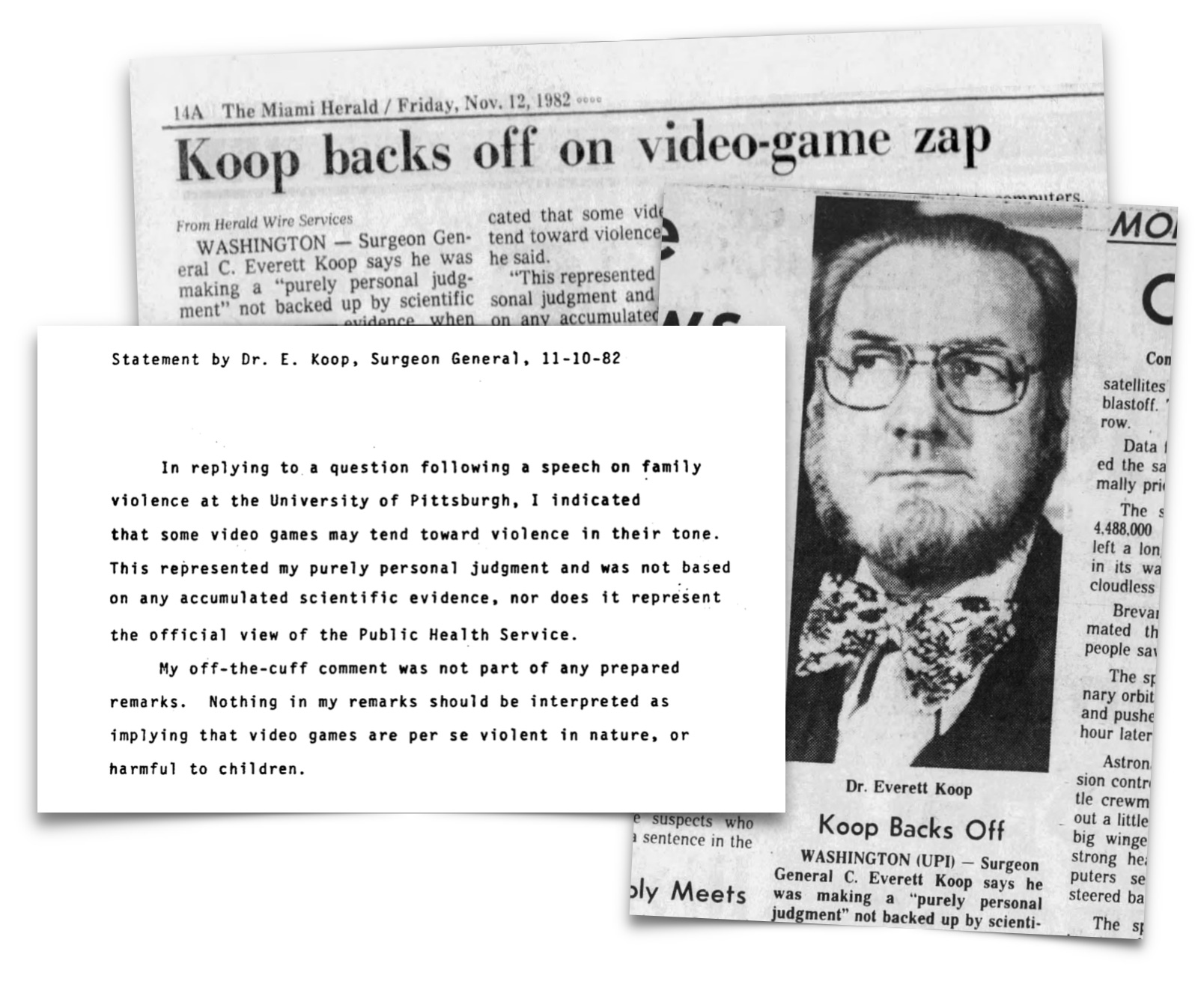

One industry representative, Glenn Braswell, wrote to the surgeon general: “Respectfully, we must remind you that your only official mandate and authority is to develop scientific evidence.” Another said emphasis should be on proven harms to kids — like cigarettes — not speculative harms. Koop would, in turn, issue a statement that made clear these were opinions only.

“My off-the-cuff comment was not part of any prepared remarks,” said Koop. “Nothing in my remarks should be interpreted as implying that videos are per se violent in natures, or harmful to children.”

It turned out the scientific evidence didn’t emerge.

In retrospect, it seems clear that Koop, as a medical authority, had the opportunity to quell unsubstantiated panic that distracted from more empirical threats to kids, like smoking. A few years later, Koop would wade into the TV violence debate, citing the 1972 Surgeon General’s Scientific Advisory Committee coming to a unanimous conclusion that violence and TV increased aggression.

That correlation is now long debunked.

This article was originally published on Pessimists Archive. It is reprinted with permission of the author.