A new CRISPR therapy was able to prevent mice from suffering seemingly any loss of cardiovascular function following a heart attack — suggesting that there may be a way to prevent the heart damage suffered by heart attack survivors.

The challenge: A heart attack occurs when the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the organ is significantly blocked. Doctors can restore the flow by surgically clearing the blockage, prescribing meds to break it up, or some combination of treatments.

Past research has found that much of the heart damage suffered following an attack can be attributed to an enzyme created by the CaMKIIδ gene, which can become overactive in response to the stress of a heart attack.

Animal studies suggested that inhibiting the enzyme can prevent damage, but designing a drug that affects only the CaMKIIδ enzyme— and not other forms of CaMKII, which play important roles throughout the body — has proven to be difficult.

The idea: Researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern have now demonstrated a way to prevent the heart attack-induced overexpression of CaMKIIδ using CRISPR base editing.

“It’s a new way of using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing.”

Rhonda Bassel-Duby

This advanced gene editing technique makes it possible to replace individual letters along one side of the DNA double helix — unlike earlier forms of CRISPR, which involve cutting through both sides, base editing is more efficient and less likely to cause unwanted, “off-target” edits.

For their study, the researchers programmed a CRISPR system to change letters at two sites in the CaMKIIδ gene — the goal was to prevent overexpression of the CaMKIIδ enzyme following a heart attack without affecting its other functions or other forms of CaMKII.

“Rather than targeting a genetic mutation, we essentially modified a normal gene to make sure it wouldn’t become harmfully overactive,” said study co-leader Rhonda Bassel-Duby. “It’s a new way of using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing.”

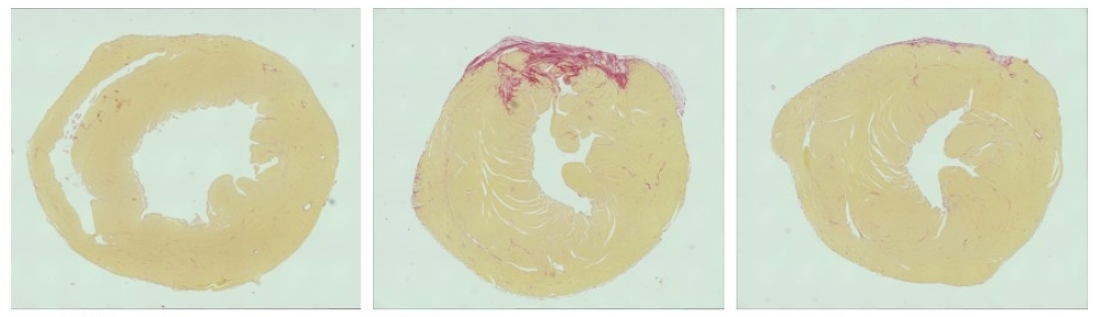

The study: To test the therapy, the researchers induced a heart attack by restricting the flow of blood into the hearts of mice for 45 minutes. They then delivered the CRISPR system directly into the hearts of some of the mice, while leaving others untreated.

All of the mice showed reduced heart function for the first 24 hours after their induced heart attacks, but while the condition of the untreated mice continued to worsen, the treated mice steadily improved.

“Usually, depriving the heart of oxygen for an extended period, as often happens in a heart attack, will damage it substantially,” said study co-leader Eric Olson. “But those animals whose heart muscles were subjected to gene editing after induced heart attacks seem to be essentially normal in the weeks and months afterward.”

The researchers saw no signs of edits to CaMKIIδ genes in organs outside the heart, nor did they notice any negative side effects in the mice during 260 days of post-treatment follow-up.

The cold water: These CRISPR edits would be permanent, so more research is needed before the therapy could be trialed in people. In particular, the team needs to study the potential off-target edits — when they checked eight sites in the genome for such edits, they did find one.

“To actually develop a gene editing drug, the standard nowadays is to look at hundreds or even thousands of sites,” Kiran Musunuru, a cardiologist and co-founder of genetic medicines company Verve Therapeutics, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Endpoints News.

The therapy might one day be administered in hospitals as a standard heart attack treatment.

Musunuru, whose company is developing its own gene therapy for heart disease, also noted the need for an alternative to the adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector used to deliver the CRISPR system into the mice’s heart cells, as AAVs can cause immune reaction problems in larger mammals.

“The biggest issue is they’re using AAV, and that’s partly out of necessity — we don’t have good ways to deliver to the heart,” he said. “The only credible way right now, in 2023, and hopefully this will change in the coming years … is AAV. But AAV and gene editing do not mix well.”

Looking ahead: If the researchers are able to get their base editing therapy fully developed, it could potentially be administered in hospitals as a standard heart attack treatment, preventing heart damage that might otherwise reduce patients’ quality of life or even lead to their deaths.

Even if this technique doesn’t pan out, though, their research shows that efforts to target CaMKIIδ are worthwhile, and if we can figure out a safe way to manipulate the gene or the enzyme, it could potentially change the lives of the millions of people who die from cardiovascular diseases every year.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].