Our eyes are responsible for gathering visual information about the world around us, but it isn’t until that info travels down to the optic nerve and into our brains that we actually see anything.

As we age, the nerve fibers that extend from our eyes to our brains lose their ability to regenerate, meaning damage to those fibers is usually permanent, leading to gradual and irreversible vision loss.

That might change in the future, though, as researchers from the University of Cambridge have developed a gene therapy that might not only get the optic nerve to self-repair, but possibly steel itself against damage in the first place.

Optic Nerve Damage

The new discovery centers on a protein called protrudin, which is key to helping neurons regenerate their long, spindly fibers, called axons, that are used to transmit nerve impulses.

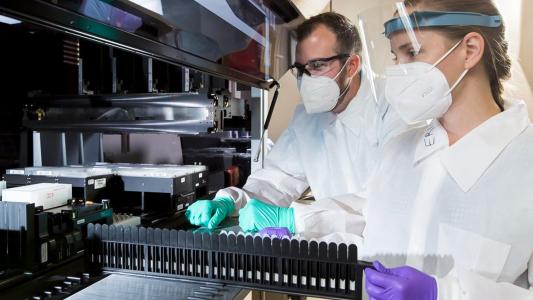

The researchers grew neurons in the lab and used a laser to damage their axons. They then used gene therapy to prompt some of the neurons to create more protrudin — causing their axons to grow longer and faster than the axons of untreated cells.

The retinas of the treated mice exhibited no signs of retinal death.

Next, the researchers tested their gene therapy in mice, injecting it right into the animals’ eyes. Two weeks later, they damaged the optic nerves of those mice, as well as some untreated mice.

Two weeks after that, they checked the status of the animals’ axons and found that the treated mice had more of the fibers regenerating (630 compared to 44 in the control) and that the axons were longer (up to 3.5 millimeters, compared to less than 0.5 mm).

As a final test, they once again injected their protrudin-boosting therapy into the eyes of live mice. Two weeks later, they extracted the animals’ whole retinas, as well as those of untreated mice, and placed them in petri dishes to grow.

After three days, half the neurons in the untreated retinas had died, but the retinas of the treated mice exhibited no signs of retinal death.

Promising Gene Therapy

All of these experiments suggest that a gene therapy designed to increase the production of protrudin in the eye could help repair or even protect the optic nerve.

According to lead author Veselina Petrova, this could be particularly useful for treating glaucoma, a leading cause of blindness worldwide.

“The causes of glaucoma are not completely understood,” she said in a press release, “but there is currently a large focus on identifying new treatments by preventing nerve cells in the retina from dying, as well as trying to repair vision loss through the regeneration of diseased axons through the optic nerve.”

Still, it’s a big leap from mouse studies to humans, and even then, we don’t know if the regrowth of axons would restore their vision, so more research is needed.

However, if the promise of this gene therapy pays off, Petrova thinks it might one day even be able to help address nerve cell damage elsewhere in the body, such as the brain or spinal cord.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].