This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

Once-fertile land is becoming desert-like at an alarming rate, but across the globe, people are using a combination of new and ancient techniques to make degraded land bloom again.

Desertification

Most plants can’t grow without nutrient-rich soil, but the amount of farmable, or “arable,” land on this planet is decreasing at a rate of about 127 square miles per day, according to UN estimates.

Much of this land is lost to desertification, a process where once-fertile land is replaced by dust and sand, usually due to a combination of climate change and human activity, such as mining, ranching, or poor farming practices.

Today, about half a billion people live in areas that have undergone desertification since the 1980s, and one-third of Earth’s total land surface is at risk of desertification.

“[Desertification and land degradation are] the greatest environmental challenge of our time,” Luc Gnacadja, executive secretary of UN’s Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), told the Guardian in 2010. “The top 20 centimeters of soil is all that stands between us and extinction.”

Desert greening

We can reclaim land lost to desertification through a process called “desert greening,” and just like there isn’t one universal cause for desertification, there isn’t just one way to make dry, dusty land fertile again.

“[Desertification and land degradation are] the greatest environmental challenge of our time.”

Luc Gnacadja

Tried and true

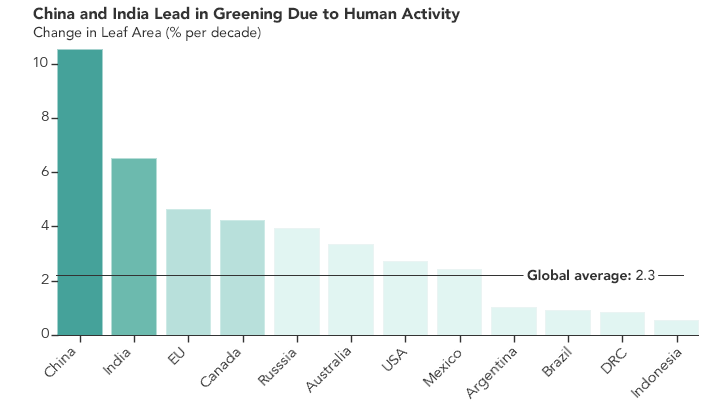

China has pursued one of the longest-running programs of desert greening. In 1978, it launched the Three-North Shelter Forest Program, also known as the “Great Green Wall,” to slow the desertification of land around the Gobi Desert.

Its plan? Plant a lot of trees.

Trees’ roots help trap valuable nutrients in soil, while their leaves create shade that helps prevent water evaporation. When dead leaves fall, they create cover that also helps keep moisture in the ground, and when they decompose, they fertilize the soil.

China’s goal is to create 88 million acres of forest by 2050, and as of 2022, it was ahead of schedule. Today, nearly a quarter of the nation’s land is forest, compared to less than 10% in 1949.

The project isn’t without its critics — some argue the Green Wall is too much of a monoculture, and the program should be planting a wider range of tree species, as that would allow the artificial forests to trap more carbon and rebuild animal ecosystems. But the overall impact appears to be positive.

“After 1999, when the tree-planting sped up, things got much better,” Wang Yinji, a farmer in China’s Gansu province, told Reuters in 2021. “Our corn grew taller. The sand that used to blow in from the east and northeast was stopped.”

Rather than relying solely on trees to combat desertification, farmers in some parts of the world have turned to strategically designed mounds of dirt known as “bunds.”

These crescent-shaped structures are dug on slopes, and their purpose is to serve as a barrier that delays water runoff. This gives precipitation time to penetrate the exposed ground on the inside part of the bund so that plants can grow.

With support from the UN, Dutch startup Justdiggit has been teaching farmers how to build bunds to regreen desertifying areas in Africa, and the impact is profound enough to be seen from space.

“The techniques … are super low tech, low investment, so they’re scalable,” Wessel van Eeden, the startup’s global director of communications, told CNN in 2022. “All we need to do is to tell the right story to the right farmer through the right platform.”

Tomorrow’s technologies

While most of today’s desert greening projects center on tried-and-true techniques like planting trees and digging bunds, a number of more advanced technologies are showing promise.

Adding clay to dry soil is a straightforward way to get it to retain more of the water crops need to grow. Mixing clay into soil is back-breaking work, though, and the process destroys underground fungal structures that help plants grow, so Norwegian cleantech company Desert Control has developed a process that makes clay nearly as thin as water.

“You can apply [Liquid Nanoclay] using any known irrigation technique,” CEO Ole Kristian Sivertsen told CNN in 2020. “You could even use a sprinkler.”

Researchers at Chongqing Jiaotong University in China, meanwhile, have developed a non-toxic paste made from cellulose, the compound in plant cell walls, that can be mixed with sandy desert soil to improve its retention of water, nutrients, and air.

During field tests, they found they could grow corn, rice, sweet potatoes and other crops on land treated with the paste, which is relatively cheap: treating one hectare costs $4,500 to $6,500, and the effect seems to last for years.

“The new method will hopefully help turn desert areas into an ideal habitat for plants,” researcher Yi Zhijian told state-run news outlet Xinhua.

The bottom line

While the above techniques and technologies can reverse desertification, they are typically costly and require long-term effort.

A desert greening project in Egypt, for example, successfully created 500 acres of forest by using treated wastewater to fertilize trees, but financial constraints meant broken treatment equipment went unrepaired, and today, only a few acres of forest remain.

Many scientists agree, then, that the best way to combat desertification is to prevent it from happening in the first place by using land more sustainably and doing everything possible to stop climate change.

“[P]reventing desertification is strongly preferable and more cost-effective than allowing land to degrade and then attempting to restore it,” according to a special report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].