This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

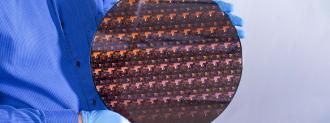

IBM has made a breakthrough in microchip technology: the world’s first 2-nanometer (nm) microchips.

Why this matters: Microchips are the brains of modern computers. They are used in almost every electronic device, from smartphones to spacecraft.

Better microchips mean more powerful devices or ones that use less energy.

IBM predicts its 2-nm microchips will be able to provide devices with a 45% boost in processing performance compared to today’s common 7-nm microchips. Alternatively, they could decrease a device’s energy consumption by 75%.

This means that our cell phones may only need to be charged every four days, our computers could get faster, and large scale data centers could drastically reduce their energy consumption and carbon emissions. According to IBM, if every data center switched to its new chips, the savings would be enough to power 43 million homes.

The microchips could also help autonomous cars process visual information or give AIs the ability to analyze mountains of astronomical data more quickly, facilitating space exploration efforts.

Truly, anything that involves computers could become more powerful if packed with these next-gen microchips — and what doesn’t involve computers?

“There are not many technologies or technological breakthroughs that end up lifting all boats,” Darío Gil, senior VP and director of IBM Research, told CNN. “This is an example of one.”

How it works: The way to increase a microchip’s performance is to increase the number of transistors packed onto it without increasing the chip’s size.

The iPhone 12’s industry leading 5-nm microchips have 11.8 billion transistors. That averages out to 134 million transistors per square millimeter.

IBM was able to fit 50 billion transistors onto the microchip the size of a fingernail (150 square millimeters). That’s 333 million transistors per square millimeter.

So, what exactly are transistors?

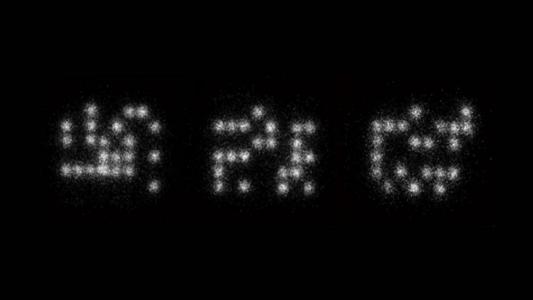

Modern computing devices operate in binary code, meaning everything they do is dictated by strings of 1s and 0s.

Transistors are like tiny faucets for computing devices, only instead of water, they control the flow of electricity. A transistor being open (with electricity flowing through it) represents a 1 in binary code, while a closed transistor represents a 0.

More transistors means faster processing of 1s and 0s, but we can’t just make bigger and bigger microchips to hold more and more transistors — the chips aren’t cheap to manufacture, and the cost goes up with size.

If we can pack more transistors onto the same sized microchip, though, we get chips that are both more powerful and more energy efficient, without dramatically increasing costs.

“In the end, there’s transistors, and everything else (in computing) relies on whether that transistor gets better or not,” Gil told Reuters.

The cold water: Manufacturing of the 2-nm microchips isn’t expected to begin until 2024 or 2025 — so these chips won’t be able to help with the current global microchip shortage.

Right now, there’s far more demand for chips than there is supply, and the pandemic deserves the lion’s share of the blame for that situation.

About 80% of chips are made in Asia, and the pandemic forced many of those facilities to temporarily shut down in early 2020. COVID-19 also affected the global supply chain, and the silicon used for microchips became more scarce because it’s also used to make vaccine vials.

Everything else in computing relies on whether transistors get better or not.

Darío Gil

Automakers also thought the pandemic would have a bigger impact on sales than it did, leading them to order too few of the chips needed for its vehicles. When sales rebounded, they ran out.

Consumer tech companies, meanwhile, needed more microchips as their sales increased. People were buying more laptops to facilitate remote work and school — and more gaming consoles to make social distancing less boring.

As if a global pandemic wasn’t difficult enough to navigate, the chip industry was also plagued by disaster in early 2021: a cold snap forced the closure of several Texas factories in February, a Japanese factory caught fire in March, and a drought in Taiwan affected factories there in April.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].