Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Duke University School of Medicine have identified a new COVID-19 antibody that is capable of neutralizing every known variant of the coronavirus.

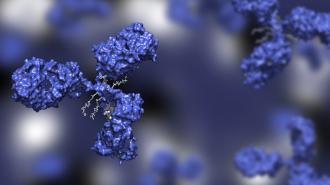

Key to its potential is that, although the new antibody attacks the virus’ notorious spike protein, it does so in a way different from other antibodies.

“SP1-77 binds the spike protein at a site that so far has not been mutated in any variant, and it neutralizes these variants by a novel mechanism,” Boston Children’s Tomas Kirchhausen said.

“These properties may contribute to its broad and potent activity.”

Researchers have discovered an antibody that neutralizes all known variants of SARS-CoV-2.

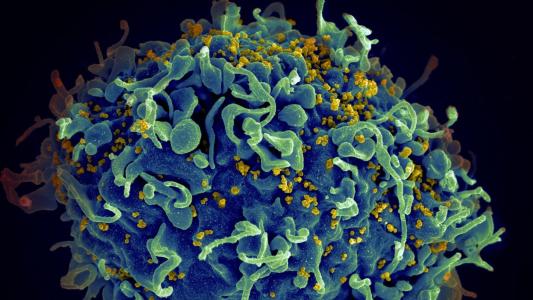

Of mice and viruses: For their study, published in Science Immunology, the team turned to mice engineered for research against another, even more rapidly mutating virus: HIV.

Such mice essentially have a built-in human immune system, capable of mimicking and optimizing our own antibody-making process, which involves cranking out iterations in a trial-and-error approach until something (literally) sticks. .

By inserting two human genes into the mice, researchers can cause them to create an array of human-esque antibodies. The mice were then exposed to the spike protein of the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, producing nine different “families” of spike-binding antibodies.

Three of the nine families were capable of stopping the original strain, but one family was able to attack all known strains.

From this group, the researchers found the most effective antibody, which they dubbed SP1-77.

To find the antibody, the team turned to mice engineered for research against another, even more rapidly mutating virus: HIV.

An all SARS-CoV-2 antibody: The team next needed to test exactly how effective it was at neutralizing the different strains, and also figure out why it was effective.

If they could find where on the virus the antibody was attacking, they could potentially identify a new target not only for new therapies, but also vaccines.

To infect us, the coronavirus binds to a special receptor on our cells called ACE2, using what is called its receptor-binding domain, or RBD. Our current antibodies, including those goosed by vaccines, boosters, and infection, stick onto this RBD and gum it up, preventing SARS-CoV-2 from ever binding with the cell.

The issue is that this part of the spike mutates frequently, and the older antibodies are no longer as effective at mucking up newer variants of the virus.

The SP1-77 antibody also gloms onto the RBD. But the researchers found that it sticks to a different spot, mucking up a different but also crucial step in the virus’s process.

Once it’s stuck onto a cell, the virus still needs to get inside. In the last step before it completely hijacks the cell, the coronavirus must merge its outer membrane with our cell’s membrane, letting its viral RNA spill into the cell. SP1-77 throws a wrench into this part of the process, blocking infection in a new way.

“SP1-77 binds the spike protein at a site that so far has not been mutated in any variant, and it neutralizes these variants by a novel mechanism,” Kirchhausen said. “These properties may contribute to its broad and potent activity.”

The antibody binds to a different spike protein site that has thus far not mutated.

What’s next: Of course, just because SP1-77 works in a mouse and a test tube does not mean it will work in humans. But if it does, the antibody could become a valuable weapon against COVID-19.

“We hope this antibody will prove to be as effective in patients as it has been in pre-clinical evaluations thus far,” Boston Children’s Frederick Alt, a senior investigator on the study, said. “If it does, it might provide a new therapeutic and also contribute to new vaccine strategies.”

As a treatment, it could involve making a new monoclonal antibody that could be infused into patients who are already sick.

But a vaccine capable of stopping multiple variants — and potentially new ones coming down the pike — would be “the holy grail of vaccines,” Thomas Russo, the chief of infectious disease at the University at Buffalo who was unaffiliated with the study, told Prevention.

Designing a new vaccine around this part of the RBD could cause our immune system to create a version of SP1-77, potentially neutralizing all circulating coronavirus strains.

The team believes their modified mouse model may prove to be a valuable tool for finding antibodies against other viruses like HIV-1 and influenza.

A bonus: SP1-77 per se isn’t the only possible benefit of the research, however; the team believes their modified mouse itself may prove to be a valuable tool for finding antibodies against other viruses, as well.

“Ultimately, this type of mouse model may be useful for generating humanized antibodies more generally, including antibodies against other diverse pathogens for which rare cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies are needed such as HIV-1 and influenza,” the authors wrote in their paper.

The study is “very early-stage proof-of-concept work” for the idea, Johns Hopkins Center for Health security expert Amesh A. Adalja told Prevention, but will need to be borne out with further research.

“We look forward to using our models to discover antibodies with therapeutic potential against other newly emerging pathogens,” Alt said in a statement.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].