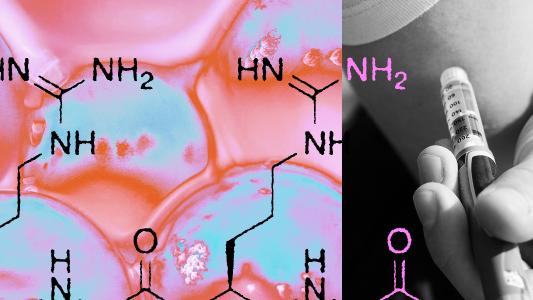

There has been a lot of excitement this year about new “anti-obesity” drugs. These drugs, made using glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1) agonists, work by suppressing your hunger. This, in turn, makes you want to eat less, so you lose weight. The excitement is merited; across several big and reputable studies, participants with obesity have been shown to lose 10–20% of their bodyweight. In a world where obesity-related diseases are killing millions each year, these GLP-1 drugs are hugely important.

But something odd happened earlier this month. A study came out that showed that when patients stopped taking one of these GLP-1 drugs (Eli Lilly’s Zepbound), they gradually put on weight again. The weight loss isn’t permanent unless you continue taking the drugs. Eli Lilly’s stock suffered a 2.3% drop on the news; investors appear to have felt that Lilly could have profited more with a longer lasting drug.

The strange thing, though, is that this study revealed nothing new. We already knew this was how these drugs worked — previous studies of the popular GLP-1 drug semaglutide also showed the effects wore off. So, what’s changed? To make sense of this and other questions about these new drugs, Freethink talked with Giles Yeo, MBE, professor of molecular neuroendocrinology at the University of Cambridge.

Investors aren’t scientists.

The problem at play here, according to Professor Yeo, is that many people outside of the medical world don’t tend to think about how drugs work. “What I think this [stock drop] tells us,” he said, “is that just because you’re an investor doesn’t mean you actually know the science of it… I think the issue is that people are misunderstanding what drugs do.”

Drugs for chronic conditions, like obesity, will generally only work as long as you’re taking them. The analogy here is with drugs for blood pressure, cholesterol, or diabetes. You have to carry on taking the drugs if they are to have their effect. Blood pressure tablets will lower your blood pressure, but as soon as you stop taking them, your blood pressure will rise again. The same is true for anti-obesity drugs. As Yeo told us, “For a drug to permanently fix something, then some rewiring must have occurred.” Surgery is permanent; molecular drugs are not.

Yeo believes that one of the reasons for the drop in Lilly’s stock is because “people think that obesity is a result of choice.” As a society, if we started to see obesity more as “a chronic relapsing disease” (as Yeo thinks it is), then the idea that we might need to take regular medication for it would not be so alien. We all recognize asthma, hypertension, or arthritis as chronic diseases requiring repeat prescriptions. If we add obesity to that list, then GLP-1 drugs will make more sense.

Something more permanent

We asked Yeo, then, if he thinks there might be something more structural or permanent that might work in treating obesity. Is there “some rewiring” that might resolve the need for regular medication? There have been promising studies in gene therapy and brain stimulation, for example.

Yeo is not so hopeful, at least at the moment. “So the brain stimulation thing,” he told us, “unless you’re saying you’re going to rewire the brain, it just doesn’t sound like it’s going to be permanent. I find it difficult to believe that, for someone who is an adult, they can have that kind of plasticity in the brain [to change permanently].”

Gene therapy might be more hopeful, but the issue here is one of complexity. “Now, for some people, there might be a singular gene that causes their obesity,” Yeo said. “But genetics wise, we know there are more genes that are subtly involved in body weight, and we do not have the capability to genetically modify [many] genes all at once.”

The only permanent and definitive way to address obesity available at the moment is bariatric or gastric bypass surgery. The most common and popular, Roux-en-Y, will “reduce the volume of the stomach to a couple of tablespoons, and then you remove a meter plus of the gut immediately coming out of the stomach, and you replumb the whole system.”

The idea behind this originally was that the surgery would lower the amount of food being absorbed and, therefore, reduce calorie intake. But, as Yeo told us, “That’s not how it works as it turns out. The effects were immediate, but it wasn’t because of malabsorption; it was because if you deliver food further down the gut, different hormones are released. If you replumb the biology, you rewire the biology. One of the hormones that works further up is the basis for the Lilly and Novo Nordisk drugs: GLP-1.”

This means that the only permanent method of obesity control — bariatric surgery — is possibly the very reason we discovered anti-obesity drugs at all. Put another way, the current drugs appear to mimic one of the main effects of surgery without having to do the surgery.

The future of anti-obesity

As we finished our conversation, we talked to Yeo about how he sees all this ending up. What will anti-obesity medicine look like in five or ten years?

“GLP-1 is only one of the gut hormones we know of, and we know of twenty hormones. And what happens is that these make you feel fuller. But the way other gut hormones work is that as you eat and food goes down, they not only inform you about how much food you’ve eaten but also what you’ve eaten. So, in other words, they tell you how much protein, fat, carb, and fiber mix there is as it goes down. So if we’re only working with one gut hormone at the moment, Mounjaro [Lilly] is working with two, GLP-1 and GIP, you can imagine a situation where we’re able to personalize treatment a bit more. We’re going to be more precise in terms of what [feeling full] we’re trying to mimic. At the moment, we’re mimicking being full. But can you mimic something more sophisticated? Can you say mimic fullness as a vegetarian, or can you mimic fullness as if you’re on keto? We have a whole palette of colors of gut hormones to play with. We’re only working with two at the moment. So, we should be more sophisticated with how we actually treat this.”